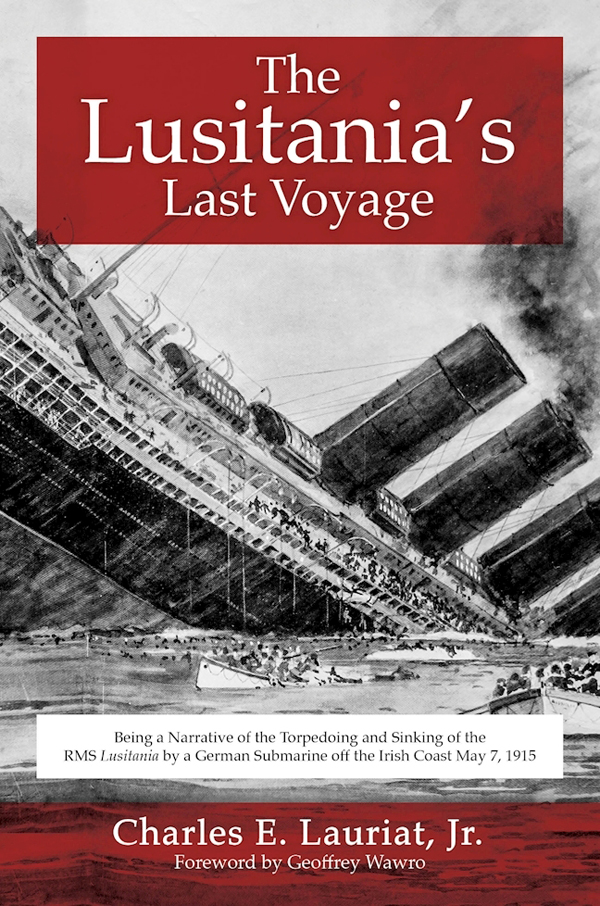

First published 1915

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2016

Introduction 2016 Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All rights to any and all materials owned by the publisher are strictly reserved by the publisher.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Matt Fetter

Cover image: Wikimedia Commons

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-0867-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0879-2

Printed in the United States of America

TO MY FATHER

WHO TAUGHT ME IN BOYHOOD TO SWIM, AND

TO KNOW NO FEAR OF THE SEA

AND

TO MY MOTHER

WHO FOUNDED THE FAITH THAT

HAS BROUGHT ME

THROUGH ALL THINGS

I DEDICATE THIS

BOOK

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Twenty minutes. Glance at a clock now and then; check it again when you finish this foreword. The time it takes to read these words may be all the time the crew and passengers aboard Cunards Lusitania had to make life-or-death decisions on the afternoon of May 7, 1915. Imagine the shock of a torpedo blast on a sunny afternoon and the immediate, sickening list to starboard, while most passengers dozed in their cabins, finished lunch, played cards, or ambled around the deck, anticipating their imminent arrival in Liverpool. How would you have reacted? What would you have done?

Most books on the Lusitania disaster follow a familiar formula. The reader is given background on the First World War, the role of neutral America, the British blockade of Germany, and the German decision to delineate a War Zone in the waters around Great Britain and declare unrestricted submarine warfare against any shipsneutral or belligerent, armed or unarmedentering that War Zone. Readers are then introduced to passengers and crew, and shown the horrors of the German attack on a beautiful spring day, just off the coast of Ireland.

Charles E. Lauriats incomparable eyewitness account of the atrocity is like none youve ever read before, and surely none youll ever read. In the first place, it is short, in which not a word is wasted. Lauriat begins his account on the day of the attack. He has finished lunch and is strolling on the deck. He feels a jolt (the first torpedo), then another (the detonation of the American-made shells and cartridges stored in the ships hold), and, in a flash, the lives of the 1,959 passengers and crew aboard are on the clock.

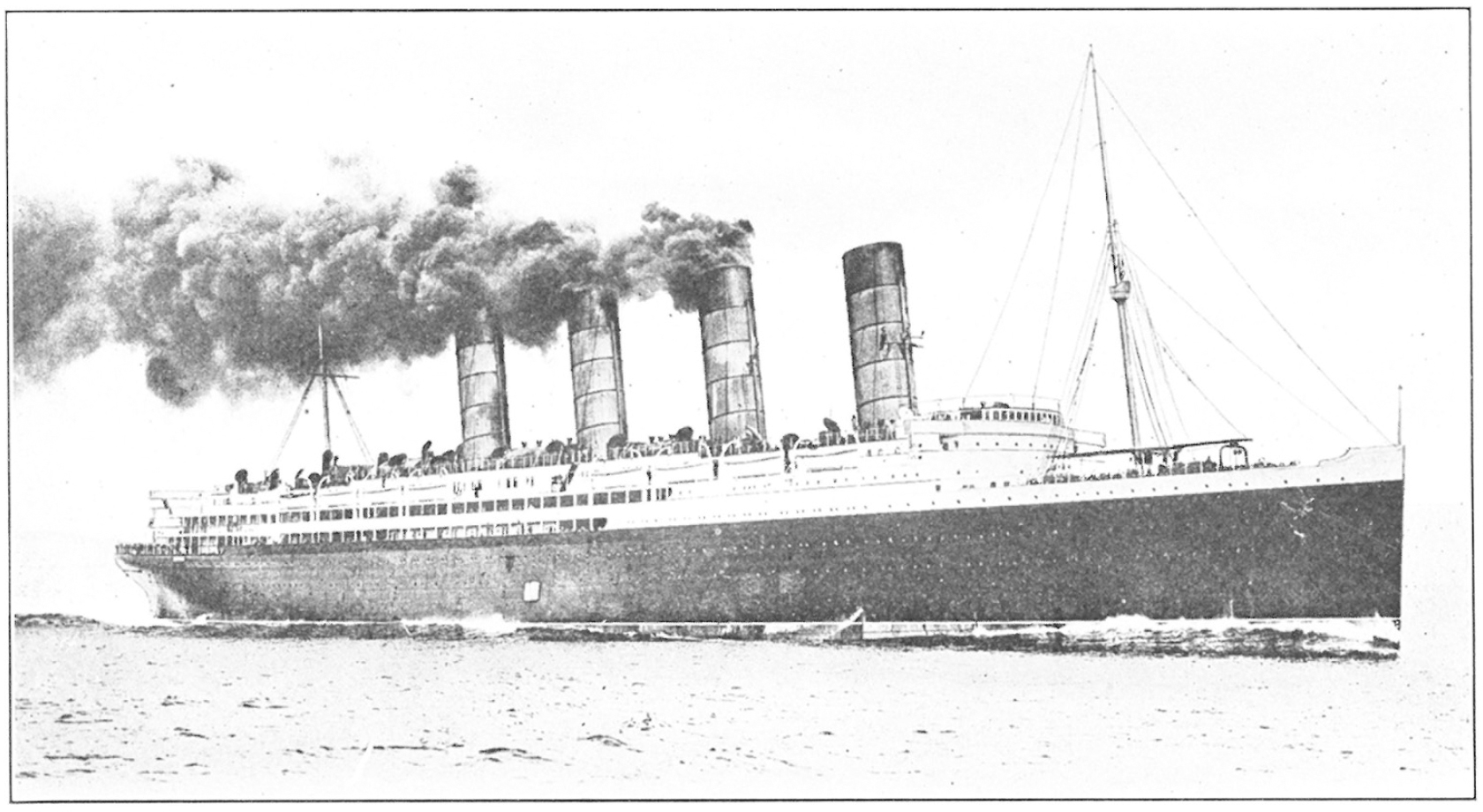

Tick-tock. The torpedo strike began the inexorable process by which great ships sink. One might hope that the Lucys modern constructionits hull space divided into twelve watertight compartmentsmight save the liner, but one could not count on it. If portholes were negligently left open (they were) or the sliding doors between compartments opened to shovel coal (they were), then it was game over. Lauriat, an American bookseller headed to England on business, showed remarkable cool-headedness. His spare, lively account guides us around the ship as it foundered.

Lauriat had been leaning on the rail talking to a couple when the explosions rocked the ship. He immediately advised them to return to their cabin to get their lifebelts. Like many he encountered, they stood stock still, shocked into inaction. Lauriat descended to his cabin, put on his lifebelt, took his passport, cash and checks, grabbed an armload of lifebelts from a bin and returned to the main deck.

The Lusitania had more than enough lifeboats for the personnel aboard. But prompt decision-making was needed at every level. The captain had to order the lifeboats lowered; the crew had to fill them with women and children first, then put the men aboard the last boats and lower them all into the sea.

Tick-tock. Pierced on its starboard side and rent internally by the explosion of the munitions stored in the bow, the Lusitania listed drastically, as water rushed in and filled the underwater compartments, thrusting the ship to the left and leaning it to the right. The ships captain would later be cleared of wrongdoing by a court of inquiry, but Lauriat knew better. He was standing on the port side, assisting the crew in lowering lifeboats when Captain William Turner appeared and ordered them to stop. Turner insisted that the Lusitania , a state-of-the-art greyhound of the Cunard fleet, wouldnt sinkshes all right, Turner said. A brave woman passenger already seated in a lifeboat doubted him in a polite voice: Where do you get your information, Captain. From the engine room, Madam, he barked back in less polite tones.

This was a critical error. There were eleven lifeboats on each side of the ship. Each boat could carry sixty passengers or more. But with the ship rolling hard to the right, it was essential to launch the portside lifeboats immediately. To wait even a minute more would mean that they would ascend high into the sky and swing inboard on their davits like Christmas ornaments.

Tick-tock. Events were happening so fast that Lauriat never had time to argue with the skipper over his decision to empty the portside lifeboats. Lauriat slid over to the starboard side and observed scenes of pitiful mayhem. Cunards skilled crews had all been conscripted into naval service, so the crewmen trying to launch the lifeboats were second-stringers and rookies.

Tick-tock. Lauriat describes the terror of the passengers as they looked up now and saw the ships four great funnels directly over them, as the ship lay nearly on its side. Nobody could cut the lifeboats loose; there were no axes to cut the ropes. Lauriat saw a man sawing at them with a pocketknife. No one could keep his feet any longer, as the ship was dunking bow first underwater and settling sideways into the deep. Lauriat saw one lifeboat, crammed with wailing women and children, still attached to the davits, plunge underwater with the ships bow.

Tick-tock. Now there were just seconds to spare. Passengers who hadnt made it into a boat climbed like alpinists to the stern, which had begun to lift high in the air. It was a natural survival instinct, but one certain to end in death.

Tick-tock. Lauriat jumped and began to swim away as fast as he could. Big ships like the Lusitania create suction when they sink, dragging down everything in their vortex. Floating in the water, not far from the ship, he watched the Lucy slip beneath the waves. The day was clear, the water calm. He saw the passengers gripping the rails and watching the sea rush up to take them. He heard their last cries as they vanished.

The story continues and is not to be missed. Lauriat traveled on to London to complete his business. He presents the German press campaign to justify the sinking as well as the whitewashed Board of Trade investigation that cleared Captain Turner of any errors in his handling of the crisis. No summary such as this can do justice to the intimacy and immediacy of Lauriats account. One must read it to know the full horror of those twenty minutes.

Geoffrey Wawro

June 2016

THE ZONE

Avert Thy gaze, O God, close tight Thine eyes!