Contents

In finishing a book many authors feel that there is much more that could have been written, that particular areas could have been expanded upon or given more detailed explanations. There can be a deep-felt reluctance to let it go, punctuated with an insatiable desire to get back into it and begin to update, amend and rewrite all over again. On the other hand the people closest to them are often relieved that the project is finally done. In the writing of a book the author will be motivated and driven to put in the late nights, exhaustive research and lengthy discussions but family and friends, who get no immediate benefit, are the ones who are the background and sometimes frontline support without whom the book would never see the light of day. In this regard there are numerous people I would like to acknowledge. Heartfelt thanks to my wife Geraldine and sons Gary Lee and Ken who offered unconditional encouragement throughout all phases of concept, research, writing and delivery; my nephew Aaron Gaynor (imbued with the patience of Joab), who forensically examined the manuscript and made corrections and offered suggestions that undoubtedly added value to the text; Joan Brennan who oversaw all the requirements of the day job in running a busy office for me in my absence; the many authors and researchers whose work I consulted in the course of writing this book; the staff at the Boole Library of University College Cork; the curator, Heather Bird, and staff of Cobh Museum. Eoin McGarry for sharing his insight into the actuality of the wreck of the ship and its physical legacy; Paddy OSullivan and his unwavering encouragement for all things Lusitania; the military veterans organisation of Grand Cayman and in particular Gerry and Ali who orchestrated my visit to speak about the Lusitania there; my former colleagues of the Irish Navy who deal on a daily basis with all the vagaries of the Eastern Atlantic that surrounds Ireland; Marcus Connaughton, author, broadcaster, producer and presenter of the Seascapes Maritime programme on Irish National Radio; Jim Halligan and fellow members of The Molgoggers Sea Shanty and Maritime Song Group who continue to offer a healthy diversion for mind and spirit when embroiled in the concentration of daily writing; finally to Eamon and Elizabeth Martin whom I have no doubt are proudly looking on from further afield.

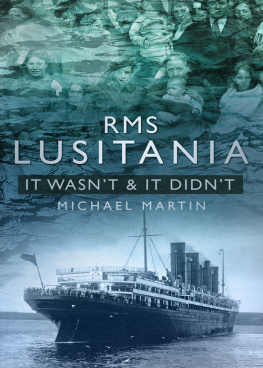

The Royal Mail Steamship RMS Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine on 7 May 1915. Twelve hundred innocent civilians lost their lives that day and became another statistic of what became known as the Great War. The fact that this was a civilian ship and was populated by non-combatants imparted the understandable impression that this action plumbed new depths of inhumanity. Unfortunately, there was nothing new about the slaughter of innocents. Such an event in peacetime would cause consternation around the globe among all peoples. Yet there were some in 1915 that perceived the attack as legitimate. There were some who believed it was justified. Their beliefs arose as a consequence of them being at war, the wording that gives latitude for unspeakable acts.

The term war embodies a great diversity of events and occurrences that always mean different things to different people. It is multifaceted, frequently reflecting division and conflict but also political intrigue, deeply held cultural aspirations, greed, cruelty, loss, human tragedy and almost always unspeakable terror for those who are at the receiving end of the mechanics of war. There can be heroism, bravery, kind-heartedness or hostility depending on which side of the conflict the perspective is formed. Centuries of mankind often perceived war to be the playing out of good against evil, right against wrong. In addition, war was often thought to be about man against man. In the classic scenario, foes line up opposite each other on a chosen site and engage on a most personal level in fighting and hand-to-hand combat until numbers, exhaustion or skill lead to one side becoming victorious. The development of weaponry and tactics from as early as Greek and Roman times began a process of distancing opponents from each other. The longbow, the crossbow, the musket and the cannon all had the effect of removing combatants from the point of lethal impact.

In simpler times, justification of the slaughter of enemies may have been easier. Protection of land, upholding of rights, consolidation of food sources and the defence of the most basic needs to survive would have compelled people to believe that war was defensive and necessary. As man developed, complicating factors increased inordinately. The acquisition of internal power, religious beliefs or control and political intrigue resulting in shifting of influence became the commonplace. It was also crucial to persuade citizens (on whose behalf war supposedly took place) that offensive actions were justified and the enemy was at fault. The repeated perspective of one side over another, the eternal narrative of right against wrong directed at the people of participating nations was to be shaped by the use of propaganda which often could be justification for defending the indefensible. Simplistic views of an arch-enemy embodying all that is evil can be comforting; however, such logic can also disguise errors of judgement and even neglect on the part of those who purportedly are fighting from the high moral ground. The loss of over 1,200 lives as a result of the sinking of RMS Lusitania in May of 1915 may fall into this category.

The outbreak of the First World War was the classic case of the shifting alliances and the balance of power among a small number of elite royalty having consequences of unimaginable proportions. It was also to become the most advanced and hideous mechanisation of the slaughter of millions of lives. Those that were killed in many cases never saw or heard the weapons of destruction that brought about their demise. Those that killed others in the scales of thousands often did little more than press some buttons or adjust some levers. However, this did not prevent soldiers in the trenches witnessing the obscene destruction of human tissue and bone among those they had just spoken to or served with. The appalling discomfort of trench life was made worse by the persistent presence of the dead in forms and shapes that should never be seen by fellow human beings. The sheer size and scale of army numbers that were going to be involved were monumental. Germany had 2 million men in uniform ready to mobilise.

One army Corps alone (out of a total of forty in the German forces) required 170 railway carriages for officers, 965 for infantry, 2,960 for cavalry, 1,915 for artillery and supply wagons, 6,010 in all, grouped in 140 trains and an equal number again for their supplies.

Millions of young men, women and children were to die between 1914 and 1918 and yet in some places life went on as normal. Business was conducted, relationships blossomed and died, newspapers were written and food was grown and harvested. Sometimes, however, the sanctity of apparent normality was shattered and those that felt physically removed from the battlefield were brought into the epicentre of destruction often when least expected. Such was the experience of those sailing on one of the worlds most luxurious liners in 1915. On a sunny afternoon in a soft Atlantic swell nearing the end of an otherwise pleasant voyage, those on RMS Lusitania had the worst aspects of the war brought to bear on them. Like many who perished in the trenches they did not see their silent enemy. Like those who had the misfortune to be on the front, they too heard the deafening report of explosives and within seconds witnessed death and destruction around them. In the small confines of a ship made tiny by the vastness of the ocean, men, women and children grappled for life over death. Most did not succeed. Of more than 1,900 people on board only 762 survived.