ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book had its origins in a conversation with my agent, Frank Weimann. I thank him for the inspiration and for his constant support and assistance. The editorial staff at Berkley supplied patience, sound advice, and technical skill in equal proportions. My colleagues at Colorado College, the U.S. Air Force Academy, and the Society for Military History bore my enthusiasms and frustrations with more goodwill than they merited. Special thanks in that regard to Sandy Papuga, Office Coordinator of the CC History Department, and to Diane Brodersen, our interlibrary loans coordinator.

I owe a particular debt to a longtime friend who, when I was floundering in the early stages of writing, offered the advice that straightened me out and kept me on track until the finish. The book is dedicated to John Wheatley, with thanks for a lot of good years.

CODA

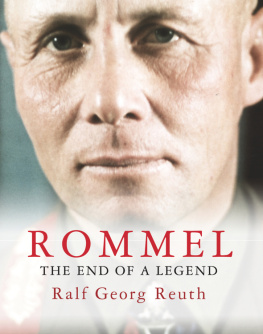

ERWIN Rommels war had come to an end six months earlier. He was in the hospital when the final and most nearly successful assassination attempt against Hitler took place on July 20, 1944. But the conspiracy had two loci. One was in Berlin, where Claus von Stauffenberg and his immediate followers sought to seize control of the centers of power in the aftermath of the bomb explosion. The other was in Paris, where another more group of officers centered on the Military Command of France, but with links to High Command West as well.

The German army historically prided itself on identification with the state but detachment from the government. In a modern state, however, the conscience of the armed forces is a public matter in the public keeping. Public dissent from public policy by serving soldiers is seldom tolerated evenor especiallyin democracies. Even when military doubters began comparing moral notes, they did not easily find common ground. Merely agreeing that the Hitler regimes crimes were sufficient to merit its overthrow absorbed a disproportionate amount of energy. The Western conspirators, while more loosely connected to each other than were their counterparts in Berlin, nevertheless understood that any successful putsch undertaken in wartime depended on transferring the loyalty of the armed forces. More specifically, Germanys future was likely to depend on what happened in the West. Continuing the war with Russia was for these men a military and political given. The Western theater offered possibilities, however limited, for negotation. If some kind of surrender proved the only option, in the last analysis it would be surrender to civilized peoples. But for even these shabby alternatives to be meaningful, the troops must be willing to accept the new order. In practice, that meant following their generalsor at least obeying orders in the first crucial days and hours of the putsch.

The problem was complicated by the large number of SS and Gestapo men present in France because of the occupation, and even more by the central role of the Waffen SS in High Command Wests order of battle. It was possible to arrest the former, but a half-dozen elite mechanized divisions could not be disarmed against their will by the stroke of a pen. That was where the field marshals came in. Rundstedt had served Kaiser, Republic, and Reich with detached loyalty; his age alone suggested that he would serve a fourth government for the brief time needed. His relief by Kluge was an unexpected bonus. During his tenure in Russia, Kluge had been sufficiently committed to Hitlers removal that he allowed the junior officers of his headquarters at Army Group Center not merely to discuss but to plan Hitlers assassination during a projected visit to the front. That project had come to nothing, but Kluge now agreed to cooperate once Hitler was dead.

Keitel and Rundstedt were sidebars. It was Rommel whose reputation and presence made him the most likelyarguably the onlysenior army officer able to override SS field commanders residual loyalty to a dead Fuehrer. It was Rommel whose public persona still shone brightly enough to give a new government the public legitimacy it needed. It was Rommel whose prospects were the best of any German officers when it came to negotiating with the Western Allies. And it was Rommel who, to the end, kept his own counsel.

Rommels involvement with the events of July 20 is in the final analysis best understood as a structure of inferences informed by wishful thinking. Although many key records are missing, it is clear that as the day for the assassination approached and the military situation worsened, the conspirators in France spoke more openly with Rommel. His responses, including facial expressions and body language, allowed his interlocutors to believe the field marshal had been won over, at least to the degree that he would support a new government after Hitler was deposed or killed. That information was, in turn, passed on to like-minded colleagues in France and communicated to Stauffenbergs group in Berlinalmost certainly in an embellished form

It has been suggested that colleagues more comfortable than Rommel with the art of intrigue sought to set up the field marshal, enveloping him in a web of innuendo that gave him no choice but to support the anti-Hitler conspiracy. It seems more reasonable to take into account the high levels of unaccustomed stress under which the men of July 20 were working. Aesopian language, allusions, and pregnant pauses were de rigeur in any case. Rommels support was considered so vital that it was scarcely remarkable that men whose own lives and honor were committed saw in him what they needed to see, and sought to use their belief as leverage on less-committed associateswho, in turn, understood as a given what at best had been a wink and a nudge.

The same pattern holds for the investigations that succeeded the assassinations failure. Apart from the effects of rigorous interrogation at the hands of the Gestapo, the temptation for accused majors and colonels to suggest or assert that ultimate responsibility rested with higher ranks was strong. Command responsibility in armed forces everywhere is usually understood as including taking care of ones own when the system seeks scapegoats. Devolving responsibility upward in the hope of involving such high levels that the investigation will be abandoned is a feature of all bureaucracies. The Reichs post-July 20 practice of Sippenhaft, punishing families for the behavior of one member, created serious and legitimate questions of where ones ultimate loyalty belonged. In the weeks after July 20, Erwin Rommels name appeared in an increasing number of dossiers and reports.

While in hospital, Rommel continued to tell his uniformed visitors openly that the war was lost. By the time he returned home in early August, he was more guarded. Kluge was dead, a suicide. Hans Speidel, Army Group Bs chief of staff, had been dismissed and would be arrested in September. Rommel still had numerous contacts and well-wishers in the army and the regime at large. He was sufficiently concerned at the prospect of assassination that he carried a pistol on his daily walks. He did not as yet seem to consider himself a subject of legitimate suspicion. His long conversations with his son, however, suggest an alternate possibility. In them, Rommel made no secret either of his belief that the war was lost, or of his criticism of the attempt on Hitlers life. Manfred Rommel took both seriously. At sixteen, he was of an age when a fathers first adult confidences are especially important. It was impossible for Rommel to deny his defeatismitself by now a capital offense. But might he have been playing one last hand close to the chest, hoping that if he should be arrested, his family might escape the worst consequences by swearing, legitimately, that to the end Rommel had denounced the Fuehrers would-be assassins?

On October 7, Rommel was summoned to Berlina special train would be sent, Keitel assured him. Rommel pleaded ill health, telling trusted friends he believed he would never get there alive. A week later, two generals called on him. Hitler, the field marshal was informed, had judged him guilty of involvement in the conspiracy against him. Despite his deep sense of betrayal, the Fuehrer offered a choice: public trial for high treason or the officers way: suicide and a state funeral, with no harm to his family. For the last time, Rommel made his decision in seconds.