Elaine Showalter, a professor emerita at Princeton University, is the author of numerous books, including the groundbreaking A Literature of Their Own: British Women Novelists from Bront to Lessing and A Jury of Her Peers: Celebrating American Women Writers from Anne Bradstreet to Annie Proulx. A frequent radio and TV commentator in the United Kingdom, she has chaired the Man Booker International Prize jury and judged the National Book Awards and the Orange Prize. She divides her time between Washington, D.C., and London.

A LSO BY E LAINE S HOWALTER

A Literature of Their Own:

British Women Novelists from Bront to Lessing

The Female Malady:

Women, Madness and English Culture, 18301980

Sexual Anarchy:

Gender and Culture at the Fin de Sicle

Sisters Choice:

Tradition and Change in American Womens Writing

Inventing Herself:

Claiming a Feminist Intellectual Heritage

Hystories:

Hysterical Epidemics and Modern Media

Teaching Literature

Faculty Towers:

The Academic Novel and Its Discontents

A Jury of Her Peers:

Celebrating American Women Writers

from Anne Bradstreet to Annie Proulx

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, JANUARY 2011

Copyright 2011 by Elaine Showalter

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material may be found at the end of the collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The vintage book of American women writers / edited and with an introduction by Elaine Showalter.1st Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-74496-8

1. American literatureWomen authors. I. Showalter, Elaine.

PS508.W7V56 2011

810.809287dc22

2010032691

www.vintagebooks.com

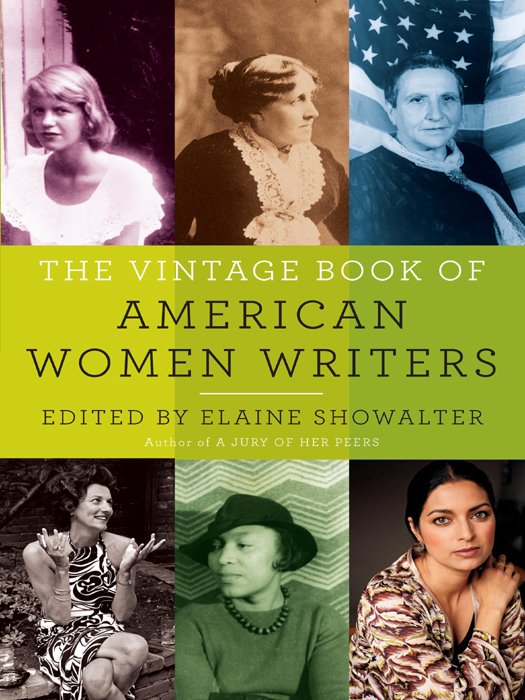

Cover design by Megan Wilson. Front cover photographs (from top left clockwise): Sylvia Plath and Lousia May Alcott The Granger Collection, New York; Gertrude Stein courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, [LC-USZ62-103680]; Jhumpa Lahiri Elena Seibert; Zora Neale Hurston courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Carl Van Vechten Collection, [LC-USZ62-79898]; Anne Sexton Gwendolyn Stewart 2010.

v3.1

Contents

From Charlotte Temple (1791):

CHAPTER VI : An Intriguing Teacher

The Widow Essays Poetry,

from The Widow Bedott Papers (1856)

Introduction

THE MOTHERS OF US ALL

Since they first began to appear in print over 350 years ago, American women writers have publicly insisted that they did not care about literary fame or immortality. Anne Bradstreet, whose book The Tenth Muse Newly Sprung Up in America was published in 1650, declared that she was contented with her humble domestic niche as a Puritan housewife and mother, and denied any interest in winning the laurel wreath or other poetic awards. If men did her the honor of reading her poems, she wrote, Give thyme or parsley wreath, I ask no bays. In other words, Bradstreet was content to be the Poet Parsleyate, rather than the Poet Laureate, and her imagery of the kitchen of Parnassus would be echoed by many American women writers who came after her.

Hoping for fame seemed unfeminine and self-aggrandizing, and they denied that such ambition inspired them to write. Rather than admitting their own ambitions, promoting their own creativity, or claiming their place in their nations literary history, the founding mothers of American literature were more likely to avoid publicity and to deprecate their own achievements. They published anonymously or under a pseudonym, and they wrote conflicted accounts of their own longings to write. Lydia Maria Child signed her first novel, Hobomok (1824), By an American; she had been warned that no woman could expect to be regarded as a lady after she had written a book. Child ruefully noted in her diary that for Christmas her husband had given her a laurel wreath, but the leaves were not very abundant.

When reviews of their works were scanty or harsh, women writers suffered in silence. But American male writers were more forthright and enterprising. When Leaves of Grass received only a handful of horrified reviews, Walt Whitman reviewed it himselfanonymouslyas a work of genius by a true American bard. Meanwhile, his great contemporary, Emily Dickinson, steadfastly refused to publish more than a handful of her poems during her lifetime.

Yet American women writers also believed that they were fully equal to the challenge of creating an American literature for a new nation. Womens rights and womens writing were closely allied after the Declaration of Independence. In 1792, Judith Sargent Murray wrote that women were equally susceptible of literary acquirement, and envisaged herself supplying the American stage with American scenes. Child and her generation of writers dedicated themselves to a literature of their native land. They shared common themes as well as individual genius. From the beginning, they wrote with sympathy about the outcast, the slave, the Native American, the madwoman. They wrote about the trials and triumphs of the creative woman. They wrote dark fables about marriage. Over the centuries, they wrote both directly and figuratively about female experience and female sexuality, from abortion to menopause. They were fascinated by the images of the circus, the carnival, and the freak in relation to the situation of the odd woman and the artist. But they also wrote about male experience and, from a masculine perspective, about cowboys, ranchers, soldiers, boxers, and killers. The range of womens writing is much wider in subject and style than is generally supposed.

However, even when they were praised and celebrated in their own day, whether as bestsellers like Harriet Beecher Stowe or Nobel Prizewinners like Pearl Buck, American women writers have tended to disappear from literary history and national memory. I explore the multiple reasons for this phenomenon in my book, A Jury of Her Peers: American Women Writers from Anne Bradstreet to Annie Proulx. But the main reason women do not figure in American literary history is because they have not been the ones to write it. And in the twenty-first century, we need historical chronology, literary contexts, and the sense of continuity as steps toward doing the fullest justice to American womens writing. We need a sense of chronology to see how women writers fit on the literary timeline of American literature, to understand them as belonging to and affecting literary traditions, and not simply as isolated and exceptional women who popped up from time to time. We need to see women writers in context, placed in relation to their contemporaries and their precursors. Finally, we need a canon of outstanding women writers over the past four centuries both to organize their history and to begin the arguments that keep literary discussion alive.