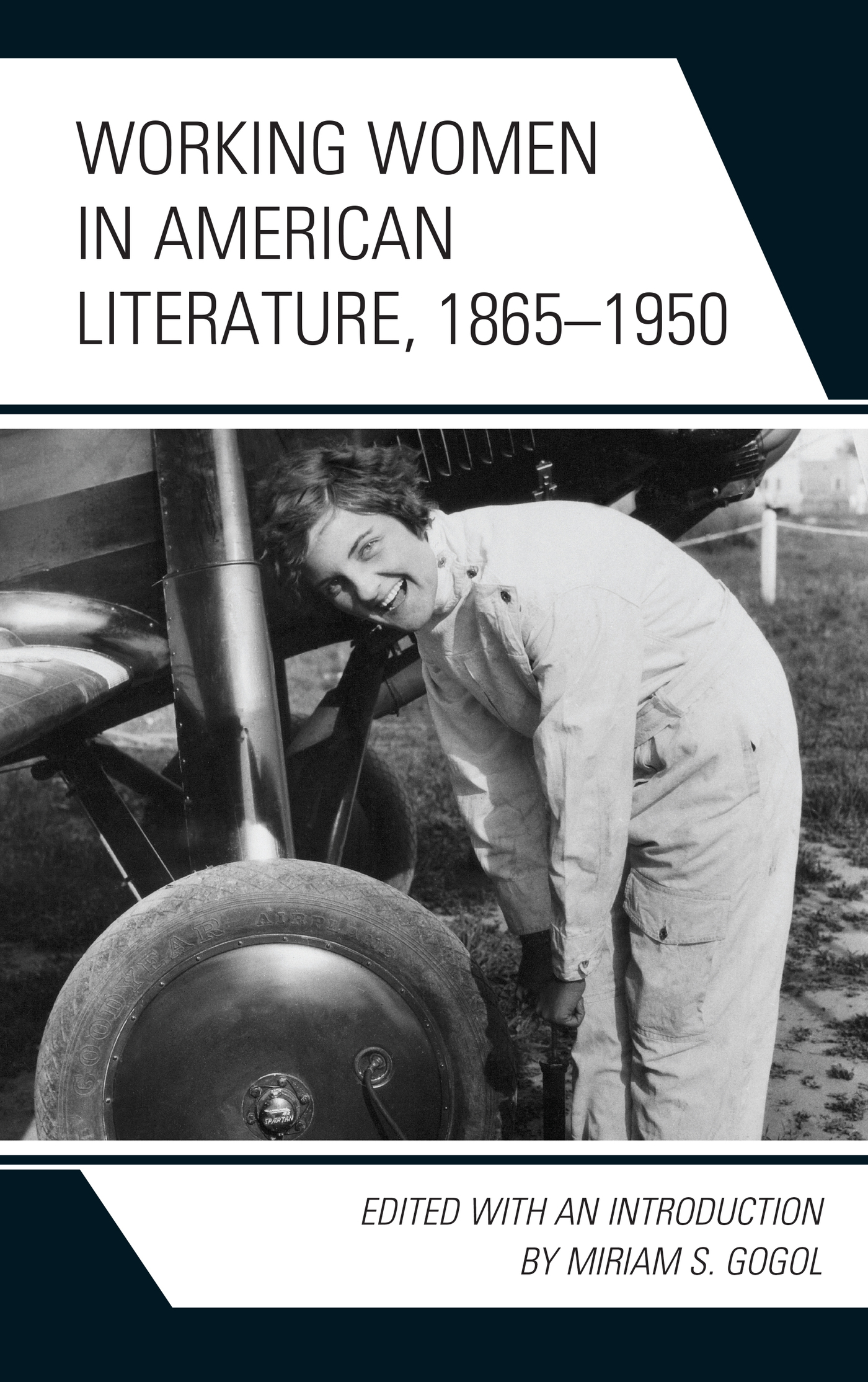

Working Women in American

Literature, 18651950

Working Women in American

Literature, 18651950

Edited with an Introduction

by Miriam S. Gogol

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2018 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gogol, Miriam, 1949- editor.

Title: Working women in American literature, 1865-1950 / [edited by] Miriam S. Gogol.

Description: Lanham : Lexington Books, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018013059 (print) | LCCN 2018025126 (ebook) | ISBN 9781498546799 (Electronic) | ISBN 9781498546782 | ISBN 9781498546782 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: American literature--19th century--History and criticism. | American literature--20th century--History and criticism. | Women employees in literature.

Classification: LCC PS173.W6 (ebook) | LCC PS173.W6 W67 2018 (print) | DDC 810.9/3522--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018013059

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Introduction

Miriam S. Gogol

In this volume, Working Women in American Literature, 18651950, you will find eight original essays by literary, historical, and multicultural critics on the subject of working women in late nineteenth- to mid-twentieth-century American literature. The collection focuses on how American working women have been presented, represented, misrepresented, and underrepresented in realistic and naturalistic fiction from this period, and in twentieth-century literary works influenced by these movements.

This book grew out of my reflections on the seminal role of working women vis--vis American literary realism and naturalismthe two most common schools of work literature, that is, literature that depicts the working poor, manual laborers, and so forth. Despite prejudices and stereotypes regarding working women from the post-Civil War era to the first half of the twentieth century, there is much to be learned from the literature of that time, especially in what is depicted and omitted in the writing of these decades. Between the end of slavery and the rise of the New Woman, we see unexpected opportunities and obstacles for women accompanying emerging technologies, reconstructed political systems, changing social norms, and most germane for our book, a new influential naturalistic and realistic literature. This collection explores the female characters of realism and naturalism not as a unified collective or a single shadow group, but as individuals to examine the relationship between the fictional and the living working women of this dynamic era.

There are few critical texts focusing on the images of working women in the realistic and naturalistic writing of this period. Some of the finest analyses include Laura Hapkes Labors Text: The Women in American Fiction; Jennifer Fleissners Women, Compulsion, Modernity: The Moment of American Naturalism; Shelley Fisher Fishkins essay on Dreiser and the Gender of Discourse; and Irene Gammels Sexualizing Power in Naturalism: Theodore Dreiser and Frederick Philip Grove.

Realism is traditionally viewed as a reaction against romanticism, for it reflects an authorial desire to represent literary reality in terms of everyday life. This close rendering of reality and emphasis on verisimilitude, along with the effort to adhere to them even at the expense of a well-constructed plot, are its main tenets. Characters appear in explicable relation to their social class, and to their own past, whereas romanticism, served, or meant to serve, the interests and aspirations of the middle class.

Naturalism, by definition, is an outgrowth of realism. It emphasized an empirical approach, stressing accuracy and objectivity. It affirmed that the only significant reality can be found in the content of experience itself. A literary sociology arose that studied the workplaces, idioms, and cultures of its protagonists; like detectives, authors hunted the clues of authenticity.

As convenient as these labels for realism and naturalism may appear, they are problematic. As Daniel Davitt Bell discusses in his aptly titled book, The Problem of American Realism, the differences among these modes are more striking than the similarities. As Bell explains, the challenge is to see William Dean Howells, Henry James, and their successors such as Stephen Crane and Theodore Dreiser as members of any single tradition or school of literature. Bell suggests that, to a large extent, realism involves more of a shift in concerns than a mode of literary presentation.

Nonetheless, the terms realism and naturalism have fundamental value in that they allow us to reference what these American fiction writers thought they were doing. Of course, that does not mean that these writers produced realistic or naturalistic texts.

Phillip J. Barrish in American Literary Realism (2011) addresses the importance of realisms engagement with its social and cultural context. This engagement, he asserts, is its essential power. Thus, to examine the presence and absence of working women in the context of the literature of this period is an opportunity to contrast what the authors thought they were doing and what the texts seem to be meant for with the best recorded truth we can summon about women of that time.

In their literary devices and conventions, neither the realist nor naturalist school provides an objective rendering of social conditions, especially those of working class women. Some deconstructions, clearly, of the determinist models which have been used to characterize these and other protagonists are required as we approach these self-defined real and natural literary worlds. We need to find the genuine voices of working women, through or beneath the characters portrayed. As Laura Hapke avers in Labors Text, to locate the plurivocal textual voicesthat is, the ways in which the voice of power in the text also records other voices, still remains to be done. So, in looking at the characterizations of working women in the fiction of this time period and in later fiction influenced by the era, we have the opportunity to contrast these images with the historical actualities of this period. Such is a goal of this collection.

In the remainder of this introductory essay, we will provide a brief and focused review of some aspects of womens lives as they are recorded in social history from 18651950. With that backdrop, the contributors in the essays to follow will examine the realistic literature of that same period. Through this process, we will see interesting contradictions arise between the realist texts and the plurivocal presences of that period.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.