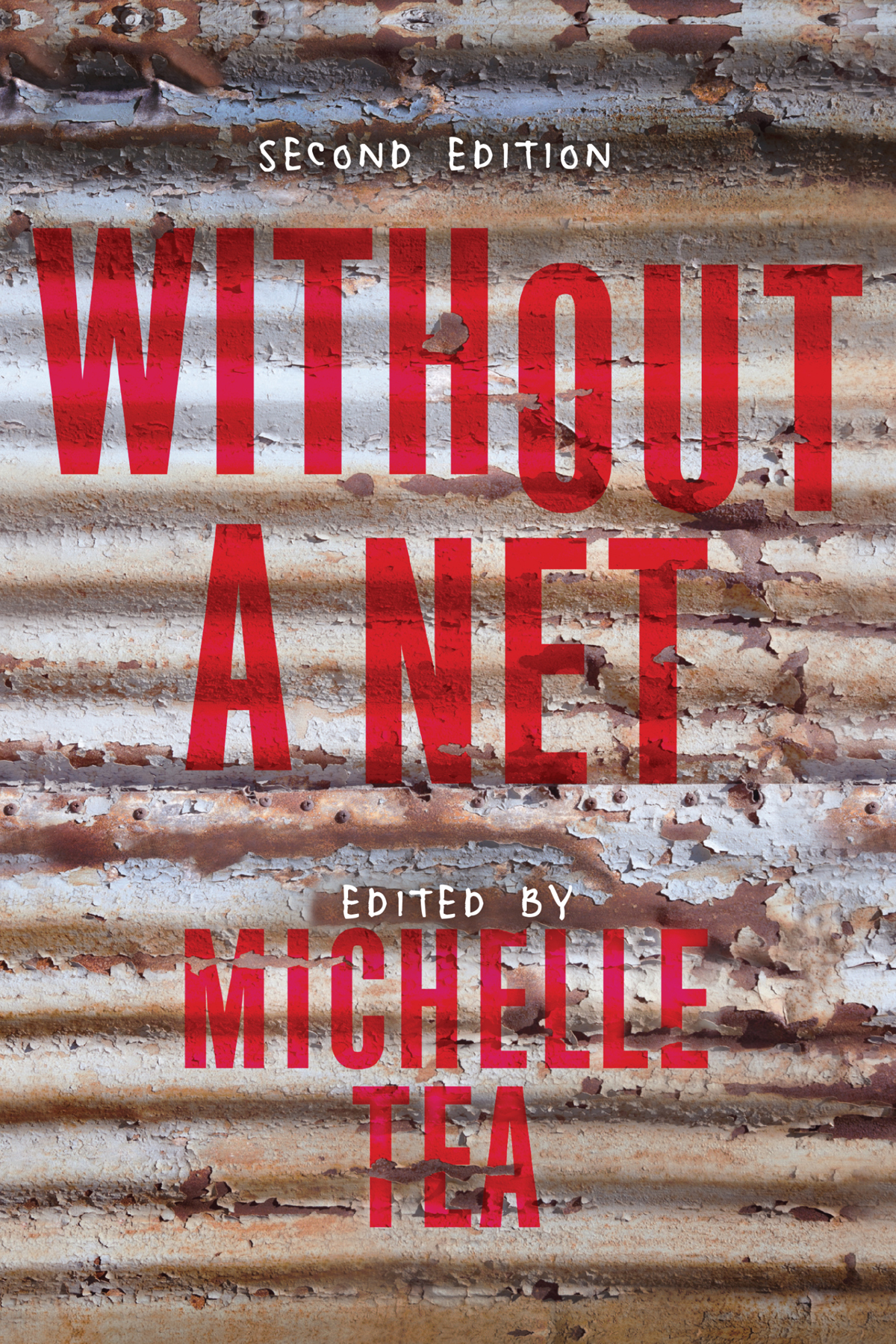

Without a Net: The Female Experience of Growing Up Working Class

First edition 2003 Michelle Tea

Revised edition 2017 Michelle Tea

Another Year Older and Deeper in Debt by Rachel Ann Brickner was originally published in Scoundrel Time literary journal in 2017: http://scoundreltime.com.

Steal Away by Dorothy Allison was originally published in the collection Trash, published by Plume in 2002. Reprinted by permission of the author.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com . Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Seal Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

sealpress.com

@SealPress

Published by Seal Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC,

a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Seal Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tea, Michelle, editor.

Title: Without a net : the female experience of growing up working class / edited by Michelle Tea.

Description: Revised edition. | New York, NY : Seal Press, [2017]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036031 (print) | LCCN 2017044694 (ebook) |ISBN 9781580056670 (ebook) | ISBN 9781580056663 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Working class women--United States.

Classification: LCC HD6095 (ebook) | LCC HD6095 .W63 2017 (print) | DDC 305.48/230973--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036031

E3-20180117-JV-NF

I DIDNT GROW UP POOR, IMPOVERISHED, DEPRIVED . W E GOT BY . W E HAD enough. And its trueI had MTV and Catholic school. No college, though, but who went to college? Kennedys! My mom had money for Depeche Mode tickets when I begged her for them. Other times, no money for a candy bar. Dont you think that if I had it I would give it to you? Really, no money for a candy bar? Really.

We werent broke, though. We were like everyone else in Chelsea, Massachusetts, and certainly better than many, the immigrant families crammed ten to an apartment, on welfare, or the families with a really bad alcoholic drinking all the money away. Our alcoholic dad split, no child support but thats O.K., my mom doesnt want to take nothing from nobody, no handouts, no charity. See? If we were really poor wed need more. Wed be on food stamps, and we were only on them that one time when Ma had a hysterectomy and couldnt work. Ma had to take off her jewelry, the thin, gold chain she wore, laden with little golden charms, a Tweety bird, Nefertiti, #1 Mom. If the case worker saw the gold they might think she was rich. A single mother, a nurse, raising two children in a slummy town, a deadbeat father run out the door, she doesnt think were poor, fears we could actually be mistaken for rich by the workers who grant us our food stamps. Such is the head fuck of class in America.

This book, Without a Net, is important because it actually acknowledges that class exists in America. It investigates the particular intersection of class and gender, and calls into the story additional intersectionalities that complicate and illuminate. In a country where a racist white electorate voted in a fascist billionaire as an answer to their economic woes, a book like this is a lightning bolt of sanity. In a country where everyone, rich and poor, claims to be middle class, denying the reality of class stratification even as it intensifies and the government wages a very clear class war, attacking the voting right, health care, and educational opportunities, this book is radical. It was a necessary book, truth-telling and fearless, when it was first published, and the addition of new voices in this fresh edition makes it even more relevant. The class problem, the problem of poverty and the strange way it is regarded in this country, is not going away, and we need writers from low-income backgrounds breaking through the actual middle-class, often rich viewpoints and experiences that dominate the media. We need to hear about the poor kid who grows up to pass as privileged among her peers. The poor kid who grows up, jumps a class or two, and sags with survivors guilt every day. The anxious persistence of scarcity issues, the PTSD of a low-income childhood. The intersections of fat and poor, of brown or black and poor, of immigrant and poor. Radical, truth-telling magic. It might not be enough to rouse the country from its stupor of denial, ignorance, and hate, but at the very least it can be a lifeline thrown from one broke girl to another, and what a revelation it is to see your experience radiated back at you in a culture that denies you even exist.

The class problem, the problem of poverty and the strange way it is regarded in this country, is not going away.

Im so grateful for the readers and teachers who have kept this book in print all these years. Im grateful to share political community with the writers in this book, to be part of a sisterhood of broke girls. No matter if we grow up and manage to do alright for ourselves, the way history haunts our psyches, the way family can be left behind, it weighs on our hearts.

May this book make its way to a new generation of readers who need it, who learn from it and take solace in it, who use it to counter the lies our culture tells us and inspire their own stories.

S AY I TELL YOU A STORY ABOUT A GIRL WHOS AFRAID OF MONEY . F ROM A young age, she learned that there didnt seem to be much of it and that hard work didnt mean one would ever have much of it. She knew this from her dads dark tan in the summer that came from working twelve-hour days in the sun, laying mulch and planting flowers in the big, bright lawns of those with houses the size of her entire apartment complex. She knew this from her mom waking up early to go to an office job, and then going to work at an Italian restaurant rather than coming home, so that after work only meant the time it took her to get from the first job to the second one.

Say she asks for a pretend checkbook for her eighth birthday and makes her mom teach her how to balance it. She loves to practice her signature, the feeling of the thin paper on the side of her pinky as she writes. She loves to imagine buying things of her own somedaya bicycle, an old VW Bug, a small blue housesomeday when she has more money than her parents.

By the time shes a teenager, she hasnt learned much more than this: Never let the balance go below zero. She spends the money from her baby-sitting jobs on thrift-store clothes, fast food, CDs. Later, she spends it on gas for her dads truck when she borrows it to get to and from her after-school job. She works at a pizza shop now, with almost all older boys and men twice her age.

S AY THIS GIRL STARTS OUT MAKING ONLY $5.25 AN HOUR, AND by the time she applies to college, her dad has left. She has only a couple hundred dollars to her name and relies on the men at work who like her to give her rides home. For a few dollars here and there, she burns CDs full of music for these menmetal and old rock, the kind of stuff that bores herwhich she steals from the internet.