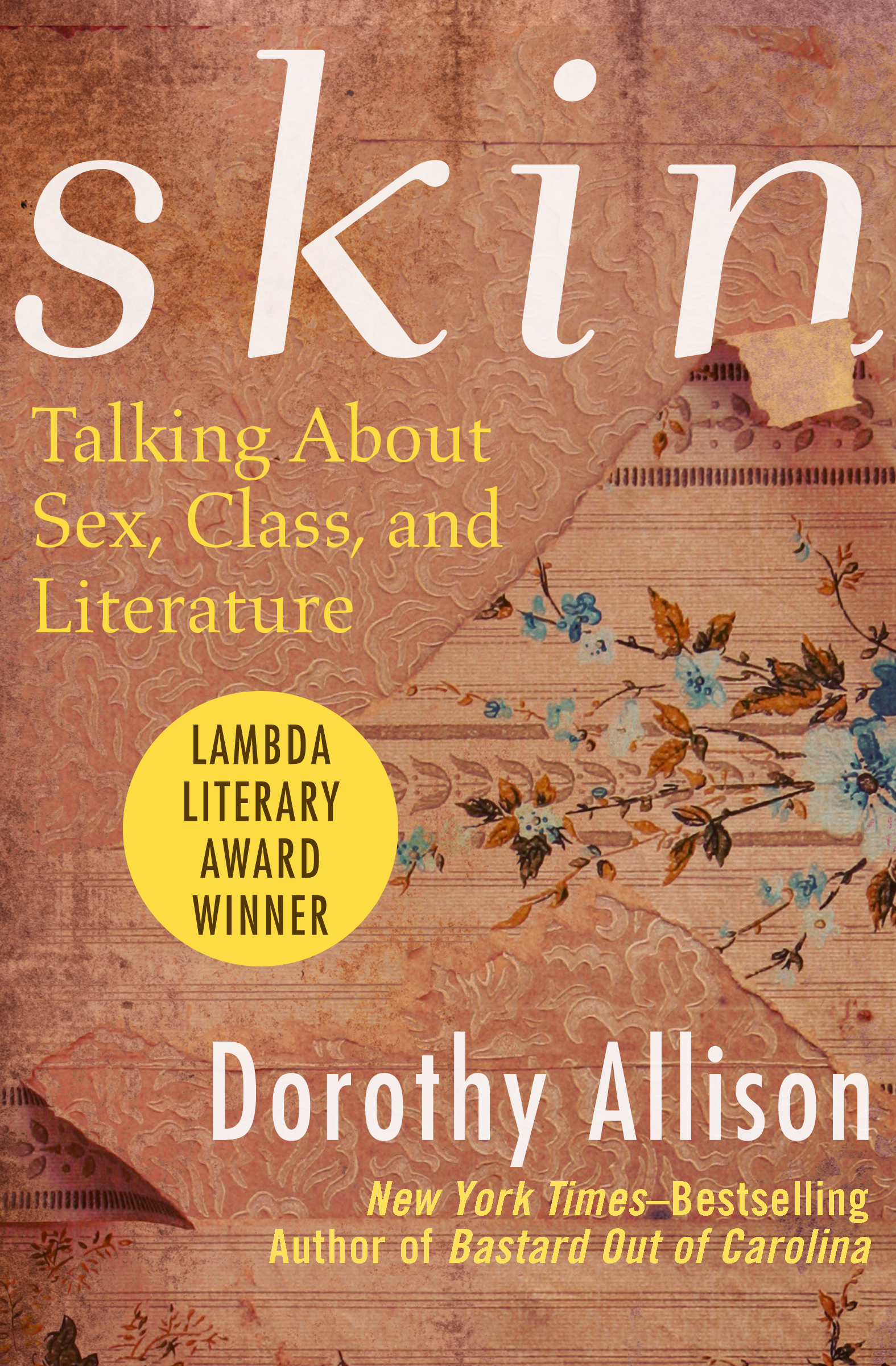

Skin

Talking About Sex, Class, and Literature

Dorothy Allison

Acknowledgments

T his book was a long time coming togethermore than a decade. It could not have been accomplished without the help and inspiration of Alix Layman, Joy Johannessen, Nancy Bereano, Jewelle Gomez, Amber Hollibaugh, Frances Goldin, Sydelle Kramer, Elly Bulkin, Diane Sabin, Pat Califia, Amy Scholder, my students who have taught me so much these last few years, and more friends and critics than I can name here. I must also acknowledge the welcome interruptions of my son, Wolf Michael. While none of my friends are responsible for my errors, Wolfan avid keyboard fenwill answer for the typos.

Preface

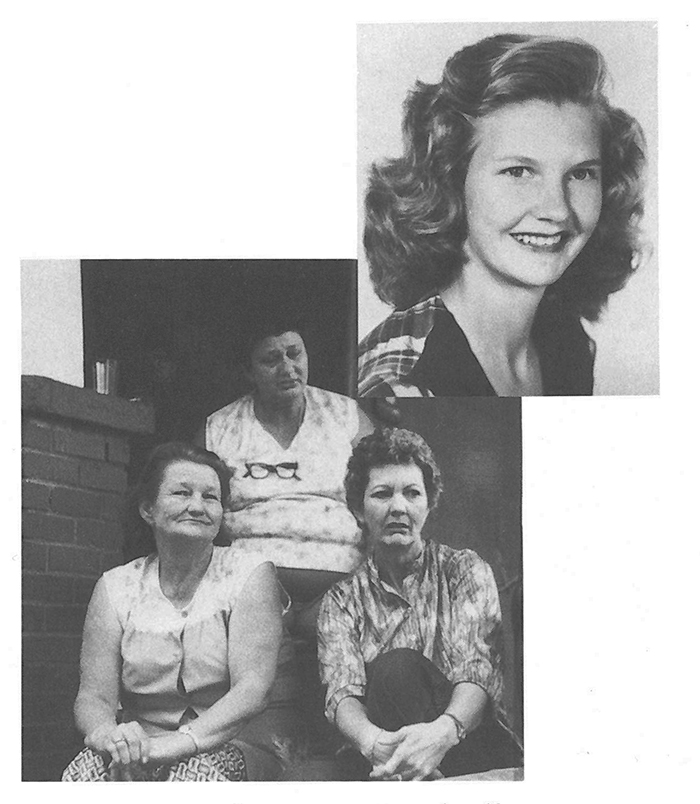

E ssays, autobiographical narratives, performances pieces, and fragmentary stories, some of these reworked into keynote addresses for gatherings of activists, writers, or gender outlaws over a decade marked by revolutionary fervor, I have reread Skin like a lost diary recalling how this piece or that one was written. Context. In so many of these pieces I reworked my personal history into a feminist or literary statementreaching for a level of understanding I never had more than roughly worked out on the page. That means there are a lot of I statements, the long, slow crafting of a sense of meaning and purpose in my own life. I was coming to understand myself and my familydesperately poor southerners with little concept of how hard and fast I had run away from themof what it meant to be a lesbian and a feminist, and a working-class escapee. And like so many of my generation, I was figuring out what I believed on the pagein those poems, essays, and stories.

The womens movement of the late sixties and seventies was often called a movement of poetsof writers and small presses, journals and local newspapersa print movement that welled up seemingly out of the consciousness raising groups that were suddenly meeting in church basements, university unions, and living rooms all over the country. The personal was political, we told one another, and that meant it was vital to share all those personal painful revelations, explorations, and discoveries. Sex was a mystery, an embattled country that, for some of us, was a scary landscape, even as it enthralled and nurtured us. Suddenly, the secret underground community of lesbians and gay men had a public presence. We were not going to continue to be afraid and defensive. We were going to march in the streets and demand respect. We were going to say what our lives meant, not let sociologists and psychiatrists diagnose us. Call us names, wed reclaim those names. Shout dyke! at me on the street, and Id shout it back. Damn right. It was a heady, fast-moving time, full of argument, exploration, and excitement. We were going to cause a revolution, change things that had seemed unchangeable. We were a nation creating itself and often doing so by making stories about our own lives.

I made a story to say who I was and who we might be, what I saw all around me that seemed to rarely make it into the versions of our lives that appeared in what we called the overground press. Some of these pieces were arguments with other writers. Some were written with a great deal more conviction and certainty than I actually felt at the time. I remember when I first put this collection together in 1993, sorting through pieces that dated back a decade and realizing that many were like those old honky-tonk answer songsthe ones where a songwriter replies to another. It wasnt God who made honky tonk angels, sang Kitty Wells, answering the dismissive contempt of the original Honky Tonk Angels, which I have pretty much forgotten. It is Kittys plaintive lyrics that have hung on for me. Just so, I wrote passionate defenses of the life I saw caricatured or dismissed in respectable magazines and journals. That meant that some of the pieces strike me now as pitiful, written in an academic or flat language too awkward to defend. But they are of their time, in their contextwith the triggers that provoked them long forgotten. Take them as letters from a battleground more mythic than remembered, and use them to figure out who you are and what you might become.

Dorothy Allison

March 2013

Contents

Context

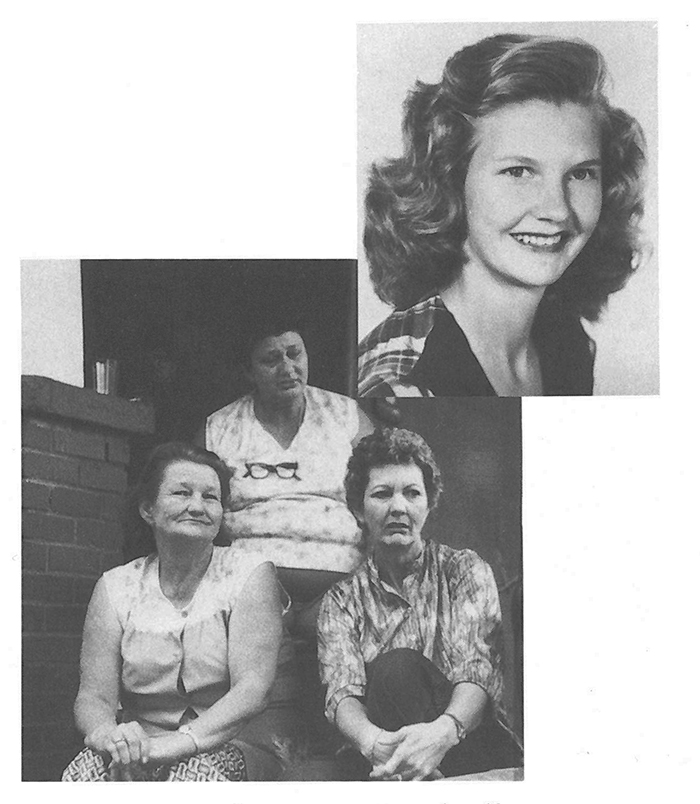

O ne summer, almost ten years ago, I brought my lover down to Greenville to visit my aunt Dot and the rest of my mamas family. We took our time getting there, spending one day in D.C. and another in Durham. I even thought about suggesting a side trip over to the Smoky Mountains, until I realized the reason I was thinking about that was that I was afraid. It was not my family I feared. It was my lover. I was afraid to take my lover home with me because of what I might see in her face once she had spent some time with my aunt, met a few of my uncles, and tried to talk to any of my cousins. I was afraid of the distance, the fear, or the contempt that I imagined could suddenly appear between us. I was afraid that she might see me through new eyes, hateful eyes, the eyes of someone who suddenly knew fully how different we were. My aunts distance, my cousins fear, or my uncles contempt seemed much less threatening.

I was right to worry. My lover did indeed see me with new eyes, though it turned out that she was more afraid of my distancing myself from her than of her fear and discomfort coming between us. What I saw in her face after the first day in South Carolina was nothing I had expected. Her features were marked with a kind of tenuous awe, confusion, uncertainty, and shame. All she could say was that she hadnt been prepared. My aunt Dot had welcomed her, served ice tea in a tall glass, and made her sit in the best seat at the kitchen table, the one near the window where my uncles cigarette smoke wouldnt bother her. But my lover had barely spoken.

Its a kind of a dialect, isnt it, she said to me in the motel that night. I couldnt understand one word in four of anything your aunt said. I looked at her. Aunt Dots accent was pronounced, but I had never thought of it as a dialect. It was just that she hadnt ever been out of Greenville County. She had a television, but it was for the kids in the living room. My aunt lived her life at that kitchen table.

My lover leaned into my shoulder so that her cheek rested against my collar bone. I thought I knew what it would be likeyour family, Greenville. You told me so many stories. But the words She lifted her hand palm up into the air and flexed the fingers as if she were reaching for an idea.

I dont know, she said. I thought I understood what you meant when you said working class but I just didnt have a context.

I lay still. Although the motel air conditioner was working hard, I could smell the steamy moist heat from outside. It was slipping in around the edges of the door and windows, a swampy earth-rich smell that reminded me of being ten years old and climbing down to sleep on the floor with my sisters, hoping it would be a little cooler there. We had never owned an air conditioner, never stayed in a motel, never eaten in a restaurant where my mother did not work. Context. I breathed in the damp metallic air-conditioner smell and remembered Folly Beach.

When I was about eight my stepfather drove us there, down the road from Charleston, and all five of us stayed in one room that had been arranged for us by a friend of his at work. It wasnt a motel. It was a guesthouse, and the lady who managed it didnt seem too happy that we showed up for a room someone else had already paid for. I slept in a fold-up cot that kept threatening to collapse in the night. My sisters slept together in the bed across from the one my parents shared. My mama cooked on a two-burner stove to save us the cost of eating out, and our greatest treat was take-out foodfried fish my stepfather swore was bad and hamburgers from the same place that sold the fish. We were in awe of the outdoor shower under the stairs where we were expected to rinse off the sand we picked up on the beach. We longed to be able to rent one of the rafts, umbrellas, and bicycles you could get on the beach. But my stepfather insisted all that stuff was listed at robbery rates and cursed the men who tried to tempt us with it. That didnt matter to us. We were overcome with the sheer freedom of being on a real vacation in a semi-public place all the time where my stepfather had to watch his temper, and of running everywhere in bathing suits and flip-flops.