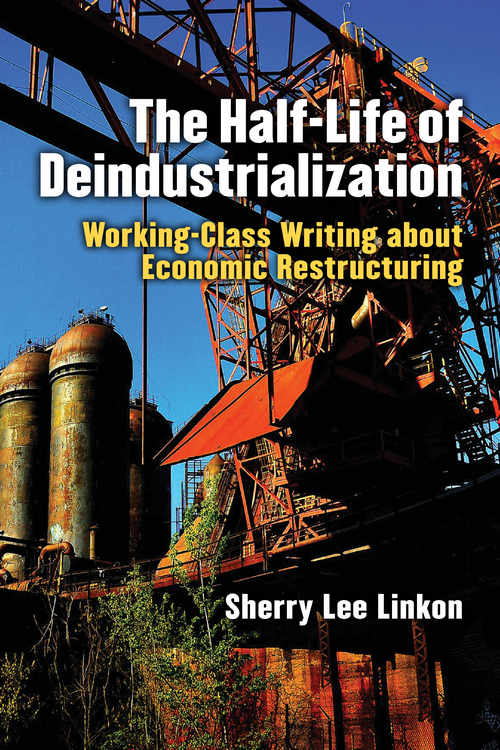

The Half-Life of Deindustrialization

Copyright 2018. University of Michigan Press. All rights reserved. May not be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except fair uses permitted under U.S. or applicable copyright law.

The Half-Life of Deindustrialization

Working-Class Writing about Economic Restructuring

Sherry Lee Linkon

University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor

Copyright 2018 by Sherry Lee Linkon

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Linkon, Sherry Lee, 1959 author.

Title: The half-life of deindustrialization : working-class writing about economic restructuring / Sherry Lee Linkon.

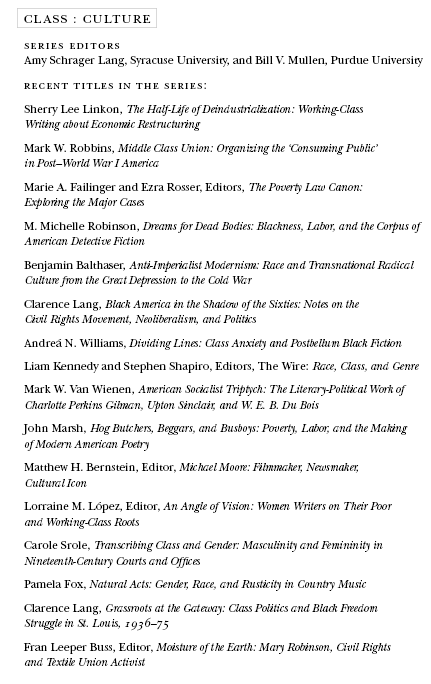

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2018. | Series: Class : culture | Includes index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052937 (print) | LCCN 2018007547 (ebook) | ISBN 9780472123704 (e-book) | ISBN 9780472053797 (paperback) | ISBN 9780472073795 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: DeindustrializationUnited StatesHistory. | Industrial policyUnited States. | Working classUnited StatesEconomic conditions. | United StatesEconomic conditions20th century. | United StatesSocial conditions20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | BUSINESS & ECONOMICS / Economic History. | LITERARY CRITICISM / American / General.

Classification: LCC HD 5708.55. U 6 (ebook) | LCC HD 5708.55. U 6 L 56 2018 (print) | DDC 338.973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052937

COVER PHOTOS : (front) Clairton Coke Works, Pennsylvania; and (back) Train Hopping Couple, Conway Yard by Michael S. Williamson, courtesy of the photographer.

Dedicated to the memory of my parents, Helene and Gordon,

and to the future of my granddaughter, Francesca

Contents

Writing a book involves many hours of solitary labor, but it is never a solo act. This book grew out of discussions with students in my Working-Class Studies courses, and its development was supported by two universities and numerous colleagues and friends. The Center for Working-Class Studies at Youngstown State University provided an intellectual home for many years. Conversations with three of its affiliatesSalvatore Attardo, Christopher Barzak, and James Rhodeshelped me begin to envision this project early on. Patty LaPresta made sure I had the time and focus to do my own work by effectively managing the collaborative work of the center. My thinking was also shaped by conversations with visiting speakers at the center, especially Dale Maharidge and George Packer, as well as with local colleagues outside the university, including Tyler Clark, John Slanina, and Hannah Woodroofe.

When I moved to Georgetown, I was fortunate to find another circle of Working-Class Studies colleagues. Carolyn Forch, Pamela Fox, Joe McCartin, Lori Merish, and Patricia OConnor offered friendship and support that helped me feel at home at Georgetown. I also appreciate the comradeship of the terrific team at the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor. I found a writing comrade in Christine Evans, whose friendship and faith in the power of art inspired me through much of this project. Amy Goldstein was a research fellow at Georgetown early in my time there, and discussions of her work on how Janesville, Wisconsin, was responding to a major plant closing reminded me that the process of deindustrialization is still active and fresh in many places. The commitment and extraordinary competence of my colleagues in the Georgetown University Writing ProgramMatthew Pavesich, Maggie Debelius, David Lipscomb, and Karen Shauphelped me balance research and writing with the programs needs. I also found support in the English Department, led by Kathryn Temple and Ricardo Ortiz. The Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice funded a research assistant, Tyler Laminack. English and American Studies colleagues, including participants in an English Department works-in-progress session and in the Americas Initiative, organized by John Tutino, offered valuable advice on drafts. Sandra Hussey, Melissa Jones, and Maura Seale at Lauinger Library made sure I had access to sometimes obscure books and materials. In more practical terms, a sabbatical and summer research award from Georgetown enabled me to complete the manuscript.

As the book developed, I presented a series of papers about deindustrialization literature at Working-Class Studies Association conferences, where I also spent many hours in informal conversations with colleagues whose work inspired me and whose enthusiasm provided essential encouragement. My thanks to Jim Catano, Nick Coles, Joseph Entin, Michele Fazio, Fred Gardaphe, Larry Hanley, and Christine Walley. I am also deeply grateful to Paul Lauter for providing advice and support throughout my career and for serving as a scholarly and professional role model. While University of Michigan Press editor LeAnn Fields deserves particular thanks for her support for and advice on this project, I also want to express my appreciation for her larger contribution to Working-Class Studies by developing the series in which this volume appears. Her commitment and insight have helped to shape and to promote this field. I am also grateful to Jenny Geyer, Kevin M. Rennells, and Anne Taylor at the Press for their work on shepherding this book through the publication process. Special thanks to the extraordinary Michael Williamson for the beautiful cover photos.

Many years ago, after an especially uncomfortable interaction with a famous working-class writer, I swore I would never again write about living authors. This project not only required me to break that oath, but it also changed my mind. I did not have the opportunity to interact directly with most of the writers discussed in this book, but four of them have been especially generous. I had known Jim Daniels and Christopher Barzak for many years, so I was not surprisedbut I am nonetheless gratefulthat they were willing to answer my many questions about their work, and I appreciate their encouragement of this project. I have never met either Dominique Morisseau or Lynn Nottage, but both trusted me with copies of their as-yet unpublished plays. Their work was incredibly important to this project, and I am deeply grateful for their willingness to share it.

This book would not exist, plain and simple, without Jack Metzgar, Tim Strangleman, and John Russo. All three read and critiqued every chapter of this book multiple times. Thanking Jack for his fierce and formative arguments, his insightful editing, and his enthusiastic cheerleading has become a tradition in Working-Class Studies, and I am grateful to join (again) the long list of scholars who rely upon him. As someone who spends a lot of time editing my colleagues work, I especially appreciate having a true critical friend in Jack, someone I trust to help me hone arguments and polish sentences. If I dont always take his advice, the error is mine, but his wisdom isas he occasionally reminds mealmost always right. Tims contribution to this book was even more crucial. We were writing in tandem, two very different books on deindustrialization, and that made the process into an extended conversation. Tim also pointed me to many of the conceptual sources that shaped this book. A few times he literally sent me books he thought I needed, all the way from England. That Tims own writing on deindustrialization is cited here so many times reflects the depth of his influence on this project. For academic writing to be a shared, interactive experience is in itself a gift, and I am thankful to have found such a generous intellectual brother.

Next page