Contents

Foreword

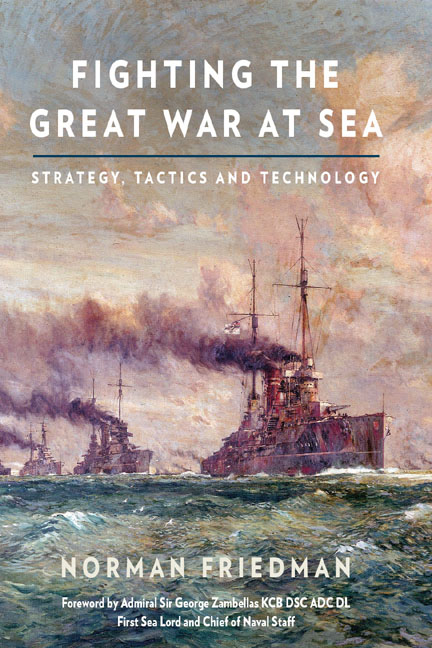

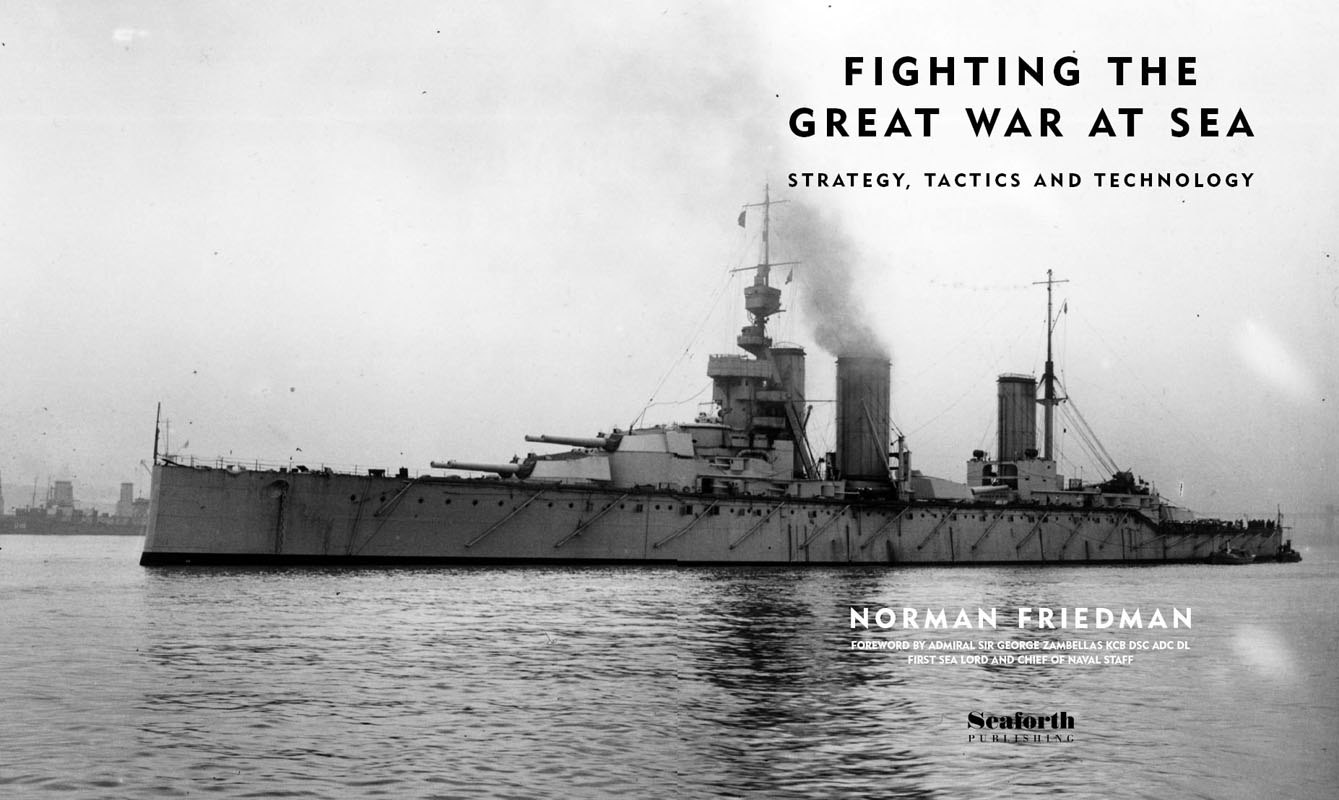

2014 marks the centenary of the start of the First World War the first truly global conflict. So, notwithstanding the deserving spotlight on the mud, barbed wire and trenches of the Western Front, this authoritative book, by an internationally respected naval historian and strategist, is a timely reminder that this war was fought across a much wider front at sea, as well as on land spanning the entire globe.

This new study also provides a showcase for Dr Friedmans rare ability to understand and explain not just strategy but also technology, and the interaction between both. Lets not forget: this was the first war in which the maritime battle-space became three dimensional, as aircraft and submarines emerged to trigger the start of a revolution in strategy, operations, tactics and technology, both at sea and from the sea.

In examining the scope and complexity of naval warfare in the First World War, Dr Friedman is also careful to relate his analysis to enduring naval strategy and contemporary maritime operations. In addition to explaining the pre-eminent global authority and performance of the Royal Navy, he helps the reader to understand that, in strategic terms, Kaisers Germany was gradually brought to its knees by the combined effect of Allied military and naval operations. This was a prelude to the strategic success of multinational and joint operations seen in many subsequent conflicts, through to the present day.

Of particular note, Dr Friedman also focuses on the nascent strategic partnership formed between the United Kingdom and the United States of America during the First World War. The sustained US Navy and Royal Navy cooperation between 1917 and the Armistice was the first practical manifestation of the Special Relationship. In the following century, the maritime foundations of our strategic TransAtlantic relationship have been very deeply established.

More broadly, Dr Friedman stresses how victory in 1918 was heavily contingent on the continuing ability of Allied nations to connect and trade across the worlds oceans, an opportunity which Allied seapower simultaneously denied to Kaisers Germany. In 1914, the United Kingdom was one of the most globalised powers, with an intimate linkage between the City and the Royal Navy underpinning both national prosperity and security. In this new century, London is still the global capital of maritime business, and the oceans remain our commercial superhighways, with 90% of the worlds trade (by volume) being carried by sea. And the White Ensign still flies around the world, in support of the United Kingdoms national ambition helping to protect our vital economic, diplomatic and security interests and, alongside our partners, helping to maintain stability in the international system at sea.

So, as well as providing a comprehensive, compelling and convincing historical analysis of the First World War at sea, this book has a contemporary relevance too. That is as it should be, because the United Kingdom, and indeed the world beyond, remains as dependent on the sea today as 100 years ago.

Admiral Sir George Zambellas KCB DSC ADC DL

First Sea Lord and Chief of Naval Staff

June 2014

Acknowledgements

M ANY FRIENDS HELPED ME with this project, whose origins extend back many years to research on various types of warships and on First World War naval tactics, strategy and technology (some of which is reflected in earlier books). The germ of my understanding of First World War British strategy (and particularly of opportunities offered by British sea power) was a discussion many years ago with Captain Peter Swartz USN in which he characterised the US Navys Maritime Strategy as the classic way sea powers confront land powers. He and I were working at the time for US Secretary of the Navy John Lehman, and I had occasion to advocate and explain the Maritime Strategy for various audiences, including at the US Naval War College and in the United Kingdom. I already felt that NATO strategy for the war which might have broken out in Europe might easily lead to something like the First World War stalemate on the Western Front. I was much attracted to the Maritime Strategy as an alternative to such a disaster. I wondered whether some analogue of the Maritime Strategy might have been a better way for Britain to have fought the First World War. What stuck in my mind then, and since, was that Captain Swartzs description was perfectly apt for Britain in the Napoleonic Wars and in the Second World War but not at all for the First World War. That made me ask why; what was different about Britain in the First World War? It is possible that the answer is that in the Napoleonic Wars and in the Second World War the fact that a single individual was the problem (Napoleon and later Hitler) made it possible to concentrate on the objective of destroying that individual and his power base. In 1914 it was not so obvious what the British war aim should have been, partly because it was not so obvious why the war had broken out. I am grateful to Dr David Stevens (chief historian of the Royal Australian Navys Seapower Centre-Australia [SPC-A]) for the opportunity to describe my approach to the First World War as keynote speaker at the 2013 King-Hall Conference, and to the audience (and the other speakers) for valuable comments. Similarly, I am grateful to audiences in New York and in Washington for their reactions to my approach, including my characterisation of the Imperial German Navy before 1914 and the wartime consequences of its pre-war nature. I have benefitted greatly from discussions with Dr Jon Sumida, with Dr Nicholas Lambert, with Dr David Stevens, with Dr Thomas Hone, with Captain Chris Page RN (former head of the Royal Navy Historical Branch), with Stephen Prince (current head of the Royal Navy Historical Branch), with David Isby, with Christopher C Wright (editor of Warship International ), with Dr Josef Strazcek (currently probably the pre-eminent historian of naval signals intelligence in the First World War), with A D Baker III, with Commander David Hobbs RN (ret), with Chris Carlson, and with Alexandre Sheldon-Dupleix of the French naval historical section. Others whose assistance I much appreciate were Ian Buxton, Raymond Cheung, Dr Steve Roberts (who, among other things, maintains a unique Shipscribe website which includes the only really detailed account of ships built for the US Emergency Shipping Board during the First World War), and Alan Raven.

As with my earlier publications, this book is based mainly on archival sources. For access to them, I would particularly like to thank Jenny Wraight, the Admiralty Librarian (and others at the Royal Navy Historical Branch); Jeremy Michel and Andrew Choong of the Brass Foundry outstation of the National Maritime Museum; and the staffs of the Public Record Office (now called The National Archive, but still the PRO to veterans), of the US National Archives (both downtown and at College Park), of the French Ministry of Defence archive at Vincennes, and of the Royal Australian Navys Seapower Centre-Australia (in effect the RAN Historical Branch). Dr Evelyn Cherpak very kindly helped me at her unique archive at the US Naval War College. I am also grateful to the staff of the US Navy Department Library. Dr David Stevens very generously provided me with copies of documents he had copied during research in the United Kingdom and the United States in connection with his own history of the Royal Australian Navy during the First World War.