Svetlana Alexievich was born in the Ukraine and studied journalism at the University of Minsk. She has received numerous awards for her writing, including a prize from the Swedish PEN Institute for courage and dignity as a writer. She won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015.

Keith Gessen is coeditor of n + 1 magazine. He has written about Russia for The Atlantic and The New York Review of Books. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

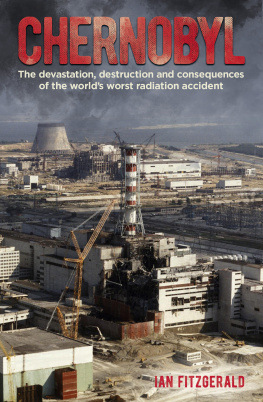

VOICES FROM CHERNOBYL

The Oral History of a Nuclear Disaster

SVETLANA ALEXIEVICH

TRANSLATION AND PREFACE BY KEITH GESSEN

PICADOR NEW YORK

Copyright 1997, 2006 by Svetlana Alexievich. Preface and translation 2005 by Keith Gessen.

First published in Russian as Trhtmobylslraia Molitva by Editions Ostojie First published in the United States by Dalkey Archive Press

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

On September II, 2001, after the first hijacked plane hit the World Trade Center, emergency triage stations were set up throughout New York City. Doctors and nurses rushed to their hospitals for extra shifts, and many individuals came to donate blood. These were touching acts of generosity and solidarity. The shocking thing about them was that the blood and triage stations turned out to be unnecessary. There were few survivors of the collapse of the two towers.

The effects of the explosion and nuclear fire at the Chernobyl power plant in 1986 were the exact opposite. The initial blast killed just one plant worker, Valeriy Khodomchuk, and in the next few weeks fewer than thirty workers and firemen died from acute radiation poisoning. But tens of thousands received extremely high doses of radiationit was an accident that produced, in a way, more survivors than victimsand this book is about them.

Much of the material collected here is obscene. In the very first interview, Lyudmilla Ignatenko, the wife of a fireman whose brigade was the first to arrive at the reactor, talks about the total degeneration of her husbands very skin in the week before his death, describing a process so unnatural we should never have had to witness it. Any little wrinkle [in his bedding], that was already a wound on him, she says. I clipped my nails down till they bled so I wouldnt accidentally cut him.

Some of the interviews are macabre. Viktor Verzhikovskiy, head of the Khoyniki Society of Volunteer Hunters and Fishermen, recalls his meeting with the regional Party bosses a few months after the explosion. They explained that the Zone of Exclusion, as the Soviets termed the land within thirty kilometers of the Chernobyl power plant, though evacuated of humans, was still filled with household pets. But the dogs and cats had absorbed heavy doses of radiation in their fur, and were liable, presumably, to wander out of the Zone. The hunters had to go in and shoot them all. Several other accounts, particularly those about the deactivation of the physical landscape in the Zonethe digging up of earth and trees and houses and their (haphazard) burial as nuclear wastealso have this quasi-Gogolian feel to them: they are ordinary human activities gone terribly berserk.

In the end its the very quotidian ordinariness of these testimonies that makes them such a unique human document. I know youre curious, says Arkady Filin, impressed into Chernobyl service as a liquidator, or clean-up crew member. People who werent there are always curious. But it was still a world of people. The men drank vodka. They played cards, tried to get girls. Or, in the words of one of the hunters: If you ran over a turtle with your jeep, the shell held up. It didnt crack. Of course we only did this when we were drunk. Even the most desperate cases are still very much part of this world of people, with its people problems and people worries. When I die, Valentina Panasevichs husband, also a liquidator, tells her as he succumbs to cancer several years after his stint at Chernobyl, sell the car and the spare tire. And dont marry Tolik. Tolik is his brother. Valentina does not marry him.

___

Svetlana Alexievich collected these interviews in the early to mid 1990sa time when anti-Communism still had some currency as a political idea in the post-Soviet space. And its certainly true that Chernobyl, while an accident in the sense that no one intentionally set it off, was also the deliberate product of a culture of cronyism, laziness, and a deep-seated indifference toward the general population. The literature on the subject is pretty unanimous in its opinion that the Soviet system had taken a poorly designed reactor and then staffed it with a group of incompetents. It then proceeded, as the interviews in this book attest, to lie about the disaster in the most criminal way. In the crucial first ten days, when the reactor core was burning and releasing a steady stream of highly radioactive material into the surrounding area, the authorities repeatedly claimed that the situation was under control. If Id known hed get sick Id have closed all the doors, one of the Chernobyl widows tells Alexievich about her husband, who went to Chernobyl as a liquidator. T d have stood in the doorway. Id have locked the doors with all the locks we had. But no one knew.

And yet, as these testimonies also make all too clear, it wasnt as if the Soviets simply let Chernobyl burn. This is the remarkable thing. On the one hand, total incompetence, indifference, and out-and-out lies. On the other, a genuinely frantic effort to deal with the consequences. In the week after the accident, while refusing to admit to the world that anything really serious had gone wrong, the Soviets evacuated tens of thousands of residents and then poured thousands of men into the breach. They dropped bags of sand onto the reactor fire from the open doors of helicopters (analysts now think this did more harm than good). When the fire stopped, they climbed onto the roof and cleared the radioactive debris. The machines they brought broke down because of the radiation. The humans wouldnt break down until weeks or months later, at which point theyd die horribly. In 1986 the Soviets threw untrained and unprotected men at the reactor just as in 1941 theyd thrown untrained, unarmed men at the Wehrmacht, hoping the Germans would at least have to stop long enough to shoot them. And as the curator of the Chernobyl Museum correctly explains, had this effort not been made, the catastrophe might have been a lot worse.

*

Much has changed in the world since these interviews were completed in 1996. Less so in Belarus. With Slobodan Milosevic in the dock at The Hague, Aleksandr Lukashenka is now Europes most brazen dictator, confidently heading for a fourth presidential term after repeatedly disappearing opposing politicians. Though usually deaf to European protests, Lukashenka did in August 2005 grant amnesty to scientist Yuri Bandazhevsky, imprisoned in 1999 after publicizing research that indicated that the effects of the Chernobyl accident were more serious than previously understood, especially in children. Bandazhevsky and his old friend and colleague Vasily Nesterenko (interviewed on page 205) have been vocal in their insistence that current studies of Chernobyl after-effects are inadequate and that the danger has not passed.

They are not being heard. A recent UN report, issued in

September 2005 by the multi-agency Chernobyl Forum, predicts that the total number of deaths attributable to the accident will be four thousandmostly residents and liquidators (clean-up workers) affected during the first days of the fire at the reactor. The report points cheerily to the fact that the vast majority of the several thousand children diagnosed with Chernobyl-related thyroid cancer have been curedfailing to indicate the likelihood of further health effects down the road. Based primarily on scientific work done under the aegis of the International Atomic Energy Agency, whose Chernobyl track record has not been good (in 1986 the IAEA blamed the disaster on operator error; it shifted the blame to the plants criminally flawed design only after the Soviet Union had ceased to exist), the report nowhere mentions the work of Bandazhevsky or Nesterenko, nor the fact that Belarus is a police state. Not implausibly, it argues that the chief cause of Chernobyl-related illness will turn out to have been the mass evacuations ordered by the Soviet government shortly after the accident. Incredibly, it goes on to opine that the biggest problem currently affecting residents of the Chernobyl region is an excess of pessimism. But plans for returning more potentially dangerous land to agricultural use continue, and children are getting sick. Youd be pessimistic, too.

Next page