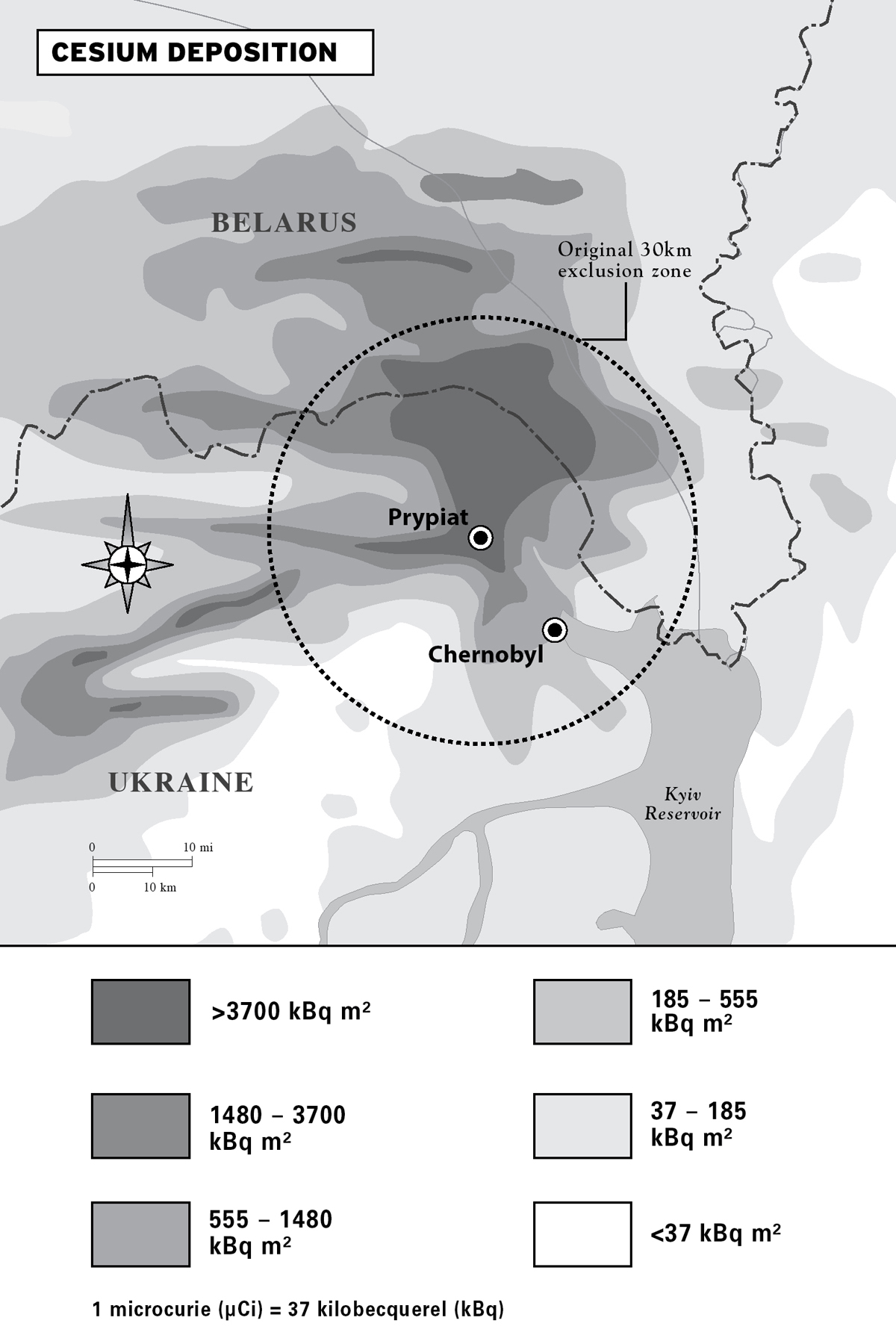

Shown over contemporary borders for reference.

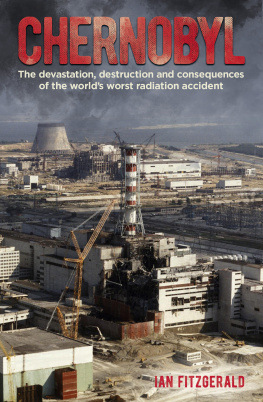

T HERE ARE eight of us on the trip to Chernobyl, marked on my Ukrainian map as Chornobyl. Besides me, there are three science and engineering students from Hong Kong who are on a tour of Russia and Eastern Europe. Then, as far as I can tell from their accent, there are four Britsthree men and one woman, all in their twenties. I soon learn that the men are indeed British, while the woman, whose name is Amanda, is proudly Irish. They are getting along quite well.

A few weeks earlier, when Amanda asked her British husband, Stuart, what he wanted to do on their forthcoming vacation, he said he wanted to go to Chernobyl. So they came, accompanied by Stuarts brother and a family friend. Two computer games had provided the inspiration for the trip. In S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl, a shooter-survival horror game, the action takes place in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone after a fictional second nuclear explosion. In Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, the main action figure, Captain Jon Price, goes to the abandoned city of Prypiat to hunt down the leader of the Russian ultranationalists. Stuart and his team decided to see the place for themselves.

Vita, our animated young Ukrainian guide, first takes us to the 30-kilometer exclusion zone and then to the more restricted 10-kilometer onetwo circles, one inside the other, with the former nuclear power plant at their center and a radius of 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) and 10 kilometers (6.2 miles), respectively. We get to see the Soviet radar called Duga, or Archa response to Ronald Reagans Star Wars Strategic Defense Initiativeby todays standards a low-tech system. It was designed to detect a possible nuclear attack from the East Coast of the United States. From there we proceeded to the city of Chernobyl, its nuclear power station, and the neighboring city of Prypiat, a ghost town that once housed close to 50,000 construction workers and operators of the destroyed plant. Vita gives us radiation counters that beep when levels exceed the established norm. In some areas, including those close to the damaged reactor, they beep nonstop. Vita then takes the dosimeters away and shuts them off, just as Soviet workers sent to deal with the consequences of the disaster did back in 1986. They had to do their work, and the dosimeters showed unacceptable levels of radiation. Vita has her own job to do. She tells us that in our whole day in the zone, we will get the same amount of radiation as an airplane passenger absorbs in an hour. We trust her assurance that the radiation levels are not too crazy.

Altogether, 50 million curies of radiation were released by the Chernobyl explosion, the equivalent of 500 Hiroshima bombs. All that was required for such catastrophic fallout was the escape of less than 5 percent of the reactors nuclear fuel. Originally it had contained more than 250 pounds of enriched uraniumenough to pollute and devastate most of Europe. And if the other three reactors of the Chernobyl power plant had been damaged by the explosion of the first, then hardly any living and breathing organisms would have remained on the planet. For weeks after the accident, scientists and engineers did not know whether the explosion of the radioactive Chernobyl volcano would be followed by even deadlier ones. It was not, but the damage done by the first explosion will last for centuries. The half-life of the plutonium-239 that was released by the Chernobyl explosionand carried by winds all the way to Swedenis 24,000 years.

Prypiat is sometimes referred to as the modern-day Pompeii. There are clear parallels between the two sites, but there are differences as well, if only because the Ukrainian city, its walls, ceilings, and even the occasional windowpane, are still basically intact. It was not the heat or magma of a volcano that claimed and stopped life there, but invisible particles of radiation, which drove out the inhabitants but spared most of the vegetation, allowing wild animals to come back and claim the space once built and inhabited by humans. There are numerous marks of the long-gone communist past on the streets of the city. Communist-era slogans are still there, and inside the abandoned movie theater, a portrait of a communist leader. Vita, our guide, says that no one can now tell who is depicted there, but I recognize a familiar face from my days as a young university professor in Ukraine at the time of the catastrophethe painting is of Viktor Chebrikov, the head of the KGB from 1982 to 1988. It has miraculously survived the past thirty years, undamaged except for a tiny hole near Chebrikovs nose. Otherwise, the image is perfectly fine. We move on.

It is strange, I think to myself, that Vita, an excellent tour guide, cannot identify Chebrikov. She also seems at a loss to explain the signs saying meat, milk, and cheese hanging from what was once the ceiling of an abandoned Soviet-era supermarket. How come, she asks, they write that in the Soviet Union there were shortages of almost everything? I explain that Prypiat was in many ways a privileged place because of the nuclear power plant, and that the workers were better supplied with agricultural produce and consumer goods than the general population. Besides, the fact that there were signs saying meat or cheese did not mean that those products were actually available. It was the Soviet Union, after all, where the gap between the image projected by government propaganda and reality was bridged only by jokes. I retell one of them: If you want to fill your fridge with food, plug the fridge into the radio outlet. The radio was telling the story of ever-improving living standards; the empty fridge had its own story to tell.