Contents

Svetlana Alexievich

CHERNOBYL PRAYER

A Chronicle of the Future

Translated by Anna Gunin and Arch Tait

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Russian as : 1997

This translation first published in Penguin Classics 2016

Text copyright Svetlana Alexievich, 1997, 2013

Translation copyright Anna Gunin and Arch Tait, 2016

The moral rights of the author and translators have been asserted

Cover photograph Jean Gaumy

ISBN: 978-0-241-27054-7

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

CHERNOBYL PRAYER

Svetlana Alexievich was born in Ivano-Frankivsk in 1948 and has spent most of her life in the Soviet Union and present-day Belarus, with prolonged periods of exile in Western Europe. She started out as a journalist and developed her own non-fiction genre which brings together a chorus of voices to describe a specific historical moment. Her first book, The Unwomanly Face of War (1985), chronicles the experience of Soviet women during the Second World War, while her second volume, Last Witnesses (1985), focuses on the same period seen through the eyes of Soviet children. They were followed by Boys in Zinc (1991), an account of the effects of war specifically the Soviet war in Afghanistan on soldiers, their families and society, and Chernobyl Prayer (1997), which features a series of monologues by people who were affected by the Chernobyl disaster. Her most recent book is Second-Hand Time (2013), a chronicle of post-Soviet life. She has won numerous international awards, including the 2015 Nobel Prize in Literature for her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our time.

Anna Gunins recent translations include Oleg Pavlovs award-winning Requiem for a Soldier (2015) and Mikail Eldins war memoirs The Sky Wept Fire (2013). Her translations of Pavel Bazhovs folk tales appear in Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov (2012), shortlisted for the 2014 Rossica Prize.

Arch Tait has translated thirty books, short stories and essays by most of todays leading Russian writers. His translation of Anna Politkovskayas Putins Russia (2004) was awarded the inaugural PEN Literature in Translation prize in 2010. Most recently, he has translated Mikhail Gorbachevs The New Russia (2016).

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

We are air: we are not earth

Merab Mamardashvili

Some historical background

Belarus To the outside world we remain terra incognita: an obscure and uncharted region. White Russia is roughly how the name of our country translates into English. Everybody has heard of Chernobyl, but only in connection with Ukraine and Russia. Our story is still waiting to be told.

Narodnaya Gazeta, 27 April 1996

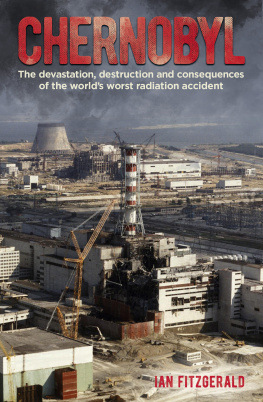

On 26 April 1986, at 01:23 hours and 58 seconds, a series of blasts brought down Reactor No. 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, near the Belarusian border. The accident at Chernobyl was the gravest technological catastrophe of the twentieth century.

For the small country of Belarus (population ten million), it was a national disaster, despite the country not having one nuclear power station of its own. Belarus is still an agrarian land, with a predominantly rural population. During the Second World War, the Germans wiped out 619 villages on its territory along with their inhabitants. In the aftermath of Chernobyl, the country lost 485 villages and towns: seventy remain buried forever beneath the earth. During the war, one in four Belarusians was killed; today, one in five lives in the contaminated zone. That adds up to 2.1 million people, of whom 700,000 are children. Radiation is the leading cause of the countrys demographic decline. In the worst hit provinces of Gomel and Mogilyov, the mortality rate outstrips the birth rate by 20 per cent.

The Chernobyl disaster released fifty million curies (Ci) of radioactivity into the atmosphere, of which 70 per cent fell upon Belarus. Twenty-three per cent of the countrys land became contaminated with levels above 1 Ci/km2 of caesium-137. For comparison, 4.8 per cent of Ukraines territory was affected and 0.5 per cent of Russias. More than 1.8 million hectares of farmland have contamination levels of 1 Ci/km or higher; roughly half a million hectares have strontium-90 contamination of 0.3 Ci/km or above. Two hundred and sixty-four thousand hectares of land have been withdrawn from cultivation. Belarus is a country of forests, but a quarter of its forests and more than half the meadows in the floodplains of the Pripyat, Dnieper and Sozh rivers are located within the radioactive contamination zone.

As a result of constant exposure to low-dose radiation, every year Belarus sees a rise in the incidence of cancer, child mental retardation, neuropsychiatric disorders and genetic mutations.

Chernobyl (Minsk: Belorusskaya

Entsiklopediya, 1996), pp. 7, 24, 49, 101, 149

Monitoring records show that high levels of background radiation were reported on 29 April 1986 in Poland, Germany, Austria and Romania; on 30 April in Switzerland and northern Italy; on 1 and 2 May in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Great Britain and northern Greece; and on 3 May in Israel, Kuwait and Turkey.

Gaseous and volatile matter was launched into the sky and dispersed around the globe: its presence was documented on 2 May in Japan; on 4 May in China; on 5 May in India; and on 5 and 6 May in the US and Canada.

In less than a week, Chernobyl became a global problem.

Consequences of the Chernobyl Accident in Belarus

[Posledstviya Chernobyl'skoy avarii v Belarusi]

(Minsk: International Sakharov Higher College of Radioecology, 1992), p. 82

Reactor No. 4, now known as the Shelter Object, still holds in its lead-reinforced concrete belly around 200 tonnes of nuclear material. This fuel is partially mixed with graphite and concrete. Nobody knows what is currently occurring inside.

The sarcophagus was hastily constructed to a unique design, one that must fill the design engineers from St Petersburg with pride. It was intended to last for thirty years, but the structure was built with a remote assembly technique, its sections joined together by robots and helicopters: hence the gaps. Today, the data suggest the breaches and cracks exceed 200 square metres in total, and aerosol radioactivity is continually leaking through them. When the wind blows from the north, traces of uranium, plutonium and caesium appear in the south. On a sunny day with the lights off, shafts of light can be seen inside the reactor hall falling from above. What are they? Rain also penetrates the building, and should moisture reach the fuel-containing material, there is the potential for a chain reaction.