THE SIX-DAY WAR

Copyright 2017 Guy Laron

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Typeset in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016957143

ISBN 978-0-300-22270-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

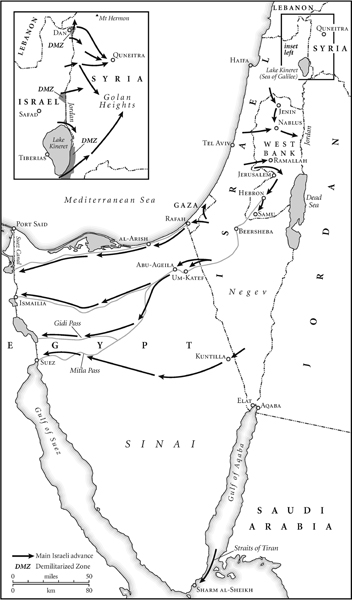

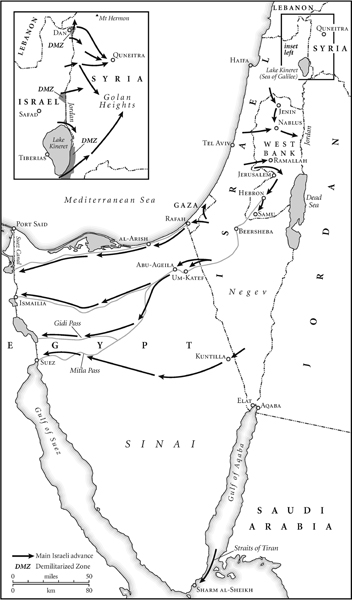

Map of the Six-Day War

PREFACE

I USED TO HATE books that started with the writers admission that he wrote the book by accident. I could never understand how someone would complete by accident a project that demanded single-minded devotion and perseverance. Having said that, I wrote this book by accident; or rather as a result of several coincidences. The first happened in the summer of 2007 when I was in the last throes of writing my dissertation. Christian Ostermann, director of the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) at the Wilson Center, invited me to participate in a book launch event that doubled as a conference on the 1967 Six-Day War. At the time, I was immersed in writing my dissertation on the 1956 Suez Crisis. Since a decade separated the two wars and I had only a short time to come up with something to say, I thought of refusing outright. But my wife, a far more practical person than I, politely pointed out that, as a jobless academic with cloudy prospects, it would be extremely foolish of me not to accept the invitation. In short, beggars cant be choosers. So, I sent back an e-mail confirming my participation and started to go over relevant documents in Czech and Arabic that were available to me.

The book I was supposed to comment on was titled Foxbats over Dimona. The authors, Gideon Remez and Isabella Ginor, claimed that the Soviet Union had planned the Six-Day War years in advance in order to stop the Israeli race toward a nuclear bomb by destroying the reactor at Dimona. The books Soviet angle was the reason I was invited, together with other scholars, to comment on the book. Two years earlier I had written an article on the 1955 CzechEgyptian arms deal that used East European archives to overcome the relative inaccessibility of Russian archives and the complete inaccessibility of relevant Arab archives. Since at the time very few people made use of East European archives to explore Middle Eastern history, I was sort of an expert.

I did not know what to make of Foxbats over Dimona. But the documents I had read before I left Israel painted a different picture. Soviet officials seemed rather surprised by the rapid turn of events in the Middle East. If there were signs of Soviet design, I could not find them. On the designated day I found myself seated on a panel that also included the authors and another Israeli professor, Yaacov Roi. In short, most of the people on the stage were Israelis who now had the chance to rehash an old internal Israeli debate in a foreign setting. If Remez and Ginor were right, then Israel did the right thing when it decided to attack its neighbors in June 1967. If they were wrong, the question of whether Israel was the aggressor was still in play.

After the event ended, several scholars approached me to ask about the documents I presented a few minutes earlier. They wondered if they could get a copy or a translation. It was at that moment that I realized there was something new in the documents I had unearthed a year earlier in the archives in Prague and in Egyptian memoirs I had found at the Library of Congress. In journalistic terms, I had a scoop. I decided then and there to produce an article of my own.

When I came back to Israel, things started to fall into place. Ehud Toledano, then director of the Graduate School of History, and Vice Rector Eyal Zisser, both at Tel Aviv University, helped me secure funding for a post-doctoral fellowship. The following months took me to archives in Prague, Berlin, Boston, and Washington. These research trips were generously funded by the Minerva Foundation, CWIHP, and, later on, the history department at Northwestern University. Mark Kramer of the Davis Center at Harvard, who is one of the leading scholars of the Communist bloc, was particularly helpful in guiding me through the RGANI holdings at the Lamont Library.

One of the more curious moments in my journey occurred in the Czech national archives, when I discovered that the document I was reading was a KGB memo. Those were still pretty rare. I had to look over my shoulder (twice!), but no commissar was there to protect the deceased empires secrets. Certainly the proudest moment was when I raided the basement of the humanities building at Tel Aviv University, where Syrian materials captured by the IDF during the war had been kept, untouched, for thirty years. The yellow pages had gathered an extraordinary amount of dust. By the time I boarded the bus home, I looked like a coal miner.

I am grateful to the editors of Cold War History and the Journal of Cold War Studies who kindly enabled me to publish my first findings in 2010. The grants I received in the following years from the Israel Science Foundation, the German-Israeli Foundation, the Leonard Davis Institute for International Relations, and the Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace enabled me to further my interest in the Six-Day War. Thanks to that funding I was able to hire excellent research assistants such as Shiri Shapira, Olga Alekseev-Semerdjiev, Anat Vatouri, Emily Neilson, and Dina Skin. Avner De-Shalit, former dean of the social sciences at the Hebrew University, and Aharon Shai, then rector of Tel Aviv University, were especially helpful in facilitating the funds needed to take a sabbatical, which I spent in 201415 at St. Antonys College, University of Oxford, as a visiting fellow.

St. Antonys was the right place to start the writing process. Eugene Rogan, the director of the Middle East Center, was a wonderful host. Two eminent scholars at Oxford Avi Shlaim and Avner Offer worked closely with me and helped me produce a well-crafted book proposal. I am very grateful to them for their good advice. During that year I also received excellent feedback from Walter Armbrust, Oscar Sanchez-Sibony, Nathan Citino, Robert Vitalis, Arne Westad, Oren Barak, and participants of the LSEs international history seminar and the Middle East Centres seminar. I should also thank Lorenz Lthi for pushing me in the past few years to internationalize the story of the war. The two workshops he organized at McGill in 2010 and 2013 were congenial venues to try out new ideas.

If it werent for Heather McCallum and Rachael Lonsdale from Yale University Press, it might have taken me another six years to write the book about the Six-Day War. But once a deadline was firmly set and the awesome opportunity to publish with Yale presented itself, I threw myself into full writing mode. I want to thank them both for expertly shepherding the editing and publication process. Safra Nimrod and Beth Humphries have also helped to improve the text.

I owe the deepest debt of gratitude to those close and near. Thank you, Sharon, for being there for me every step of the way, emotionally and intellectually. It meant the world to me. We made this book together and hopefully there will be more adventures to share. Tal, as we both know, the Six-Day War has accompanied you for too many years. As a baby I tried to make you laugh by blurting out the name of the Egyptian minister of war (never worked) and as a toddler I cured your bouts of insomnia by telling you about the 1966 Baath coup (worked like magic). I am putting this project to bed now, but I hope to develop a new set of obsessions pretty soon.

Next page