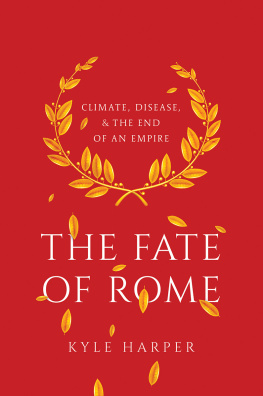

THE FATE

OF ROME

T HE P RINCETON H ISTORY OF THE A NCIENT W ORLD

THE FATE

OF ROME

CLIMATE, DISEASE, AND

THE END OF AN EMPIRE

KYLE HARPER

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art courtesy of Shutterstock

Jacket design by Faceout Studio, Spencer Fuller

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-16683-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017952241

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon Next LT Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

For Sylvie, August, and Blaise

In my beginning is my end. In succession

Houses rise and fall, crumble, are extended,

Are removed, destroyed, restored, or in their place

Is an open field, or a factory, or a by-pass.

Old stone to new building, old timber to new fires,

Old fires to ashes, and ashes to the earth

Which is already flesh, fur and faeces,

Bone of man and beast, cornstalk and leaf.

T. S. Eliot, East Coker

C ONTENTS

Prologue:

Natures Triumph 1

Chapter 1

Environment and Empire 6

Chapter 2

The Happiest Age 23

Chapter 3

Apollos Revenge 65

Chapter 4

The Old Age of the World 119

Chapter 5

Fortunes Rapid Wheel 160

Chapter 6

The Wine-Press of Wrath 199

Chapter 7

Judgment Day 246

Epilogue:

Humanitys Triumph? 288

M APS

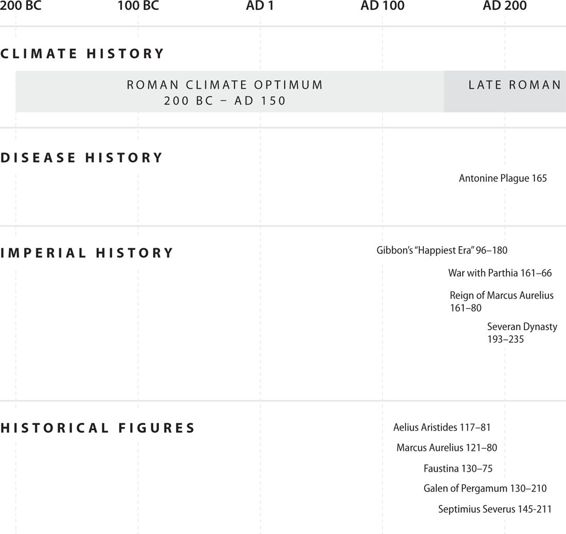

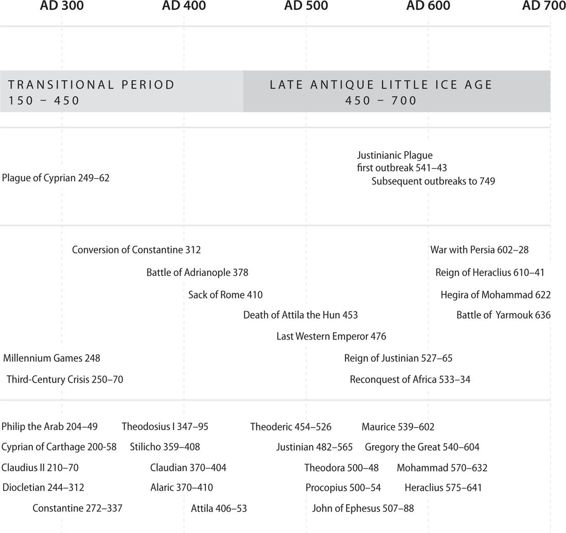

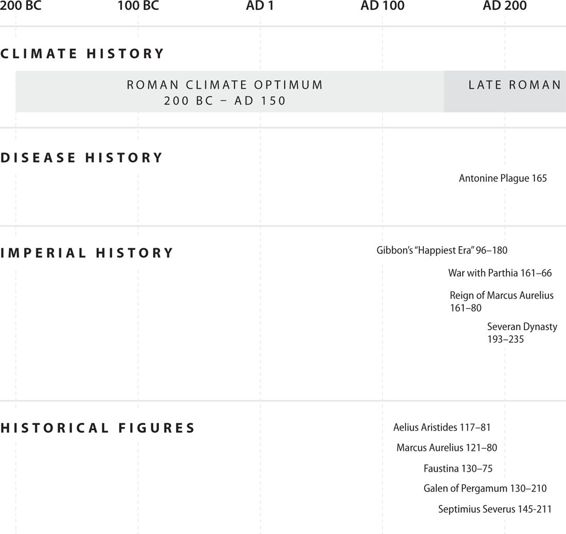

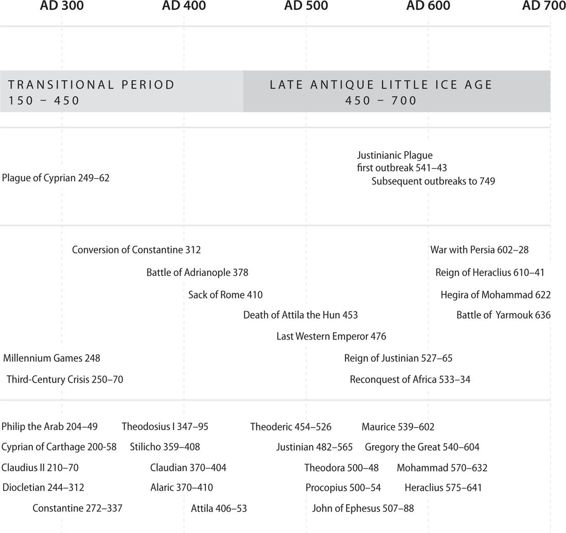

T IMELINE

THE FATE

OF ROME

Prologue

NATURES TRIUMPH

Sometime early in the year AD 400, the emperor and his consul arrived in Rome. No one alive could remember a time when the emperors actually resided in the ancient capital. For over a century, the rulers of the empire had passed their days in towns closer to the northern frontier, where the legions held the line between, as the Romans thought of it, civilization and barbarism.

By now, an official imperial visit to the capital counted as a pretext for magnificent fanfare. For even without the emperors, Rome and its people remained potent symbols of the empire. Some 700,000 souls still called the city their home. They enjoyed all the amenities of a classical town, on an imperial scale. A proud inventory from the fourth century claimed that Rome had 28 libraries, 19 aqueducts, 2 circuses, 37 gates, 423 neighborhoods, 46,602 apartment blocks, 1,790 great houses, 290 granaries, 856 baths, 1,352 cisterns, 254 bakeries, 46 brothels, and 144 public latrines. It was, by any measure, an extraordinary place.

The arrival of an emperor on the scene set in motion a sequence of carefully staged civic rituals, designed to assure the City of its preeminence within the empire and, at the same time, to assure the empire of its pre-eminence among all the principalities of the world. The people, as the proud stewards of the imperial tradition, were keen judges of this kind of ceremony. Rome, they were pleased to be reminded, was a city greater than any the air encompasses on the earth, whose grandeur no eye can behold, whose charms no mind can measure.

A grand imperial procession coiled its way to the forum. Here was where Cato and Gracchus, Cicero and Caesar, had made their political fortunes. The ghosts of history were welcome companions as the crowd gathered on this day to hear a speech of praise honoring the consul, Stilicho. Stilicho was a towering figure, a generalissimo at the zenith of his power. His imposing presence was affirmation that peace and order had returned to the empire. The

The poet who spoke in the consuls honor was named Claudian. An Egyptian by birth, whose native tongue was Greek, Claudian made himself one of the last true giants of classical Latin verse. His words betray the sincere awe the capital inspired in a visitor. Rome was the city that, sprung from humble beginnings, has stretched to either pole, and from one small place extended its power so as to be co-terminous with the suns light. She was the mother of arms and of law. She had fought a thousand battles and extended her sway oer the earth. Rome alone received the conquered into her bosom, and like a mother, not an empress, protected the human race with a common name, summoning those whom she has defeated to share her citizenship.

This was not poetic fancy. In Claudians time, proud Romans could be found from Syria to Spain, from the sands of Upper Egypt to the frostbit frontiers of northern Britain. Few empires in history have achieved either the geographical size or the integrative capacities of the Roman commonwealth. None have combined scale and unity like the Romansnot to mention longevity. No empire could peer back over so many centuries of unbroken greatness, advertised everywhere the eye wandered in the forum.

For nearly a millennium, the Romans had marked their years by the names of the consuls: thus Stilichos name was inscribed in the annals of the sky. In gratitude for this immortal honor, the consul was expected to entertain the people in traditional Roman style, which is to say with expensive and sanguinary games.

We know thanks to Claudians speech that the people were presented an exotic menagerie worthy of an empire with global pretensions. Boars and bears were brought from Europe. Africa gave leopards and lions. From India came the tusks of elephants, though not the animal itself. Claudian imagines the boats crossing sea and river with their wild cargo. (And he includes an unexpected but wonderful detail: the sailors were terrified by the prospect of sharing their ship with an African lion.) When the hour came, the glory of the woods and the marvels of the south would be

Map 1.The Roman Empire and Its Largest Cities in the Fourth Century

Claudians speech pleased its hearers. The senate voted to honor him with a statue. But the confident notes of his oration were soon drowned out, first by brutal siege and then the unthinkable. On August 24 of 410, for the first time in eight hundred years, the Eternal City was sacked by an army of Goths, in what was the most dramatic single moment in the long train of events known as the fall of the Roman Empire. In one city the earth itself perished.

How could this happen? The answers we might give to such a question will depend very much on the resolution of our focus. On small scales, human choice looms large. The Romans strategic decisions in the years leading up to the calamity have been endlessly second-guessed by arm-chair generals. On a larger canvas, we might identify structural flaws in the imperial machinery, such as the exhausting civil wars or the exorbitant pressures on the fiscal apparatus. If we zoom even further out, we might view the rise and fall of Rome as the unavoidable fate of all empires. Something along those lines was the final verdict of the great English historian of Romes fall, Edward Gibbon.

Next page