A cknowledgements

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities Research Council of Canada, using funds provided by the Canada Council, and a grant from the Canada-Iceland Foundation. The following organizations also provided strong encouragement and support during the planning of this volume:

The Icelandic Festival of Manitoba

The Icelandic National League

The North American Publishing Company Limited

The Betel Home Foundation

Thanks are due to Dr. Jhannes Nordal, Chairman of Hi islenzka fornritaflag and Agst Bvarsson for their kind permission to use the maps of the original editions from which this translation was made. The place names have been adapted to the translation.

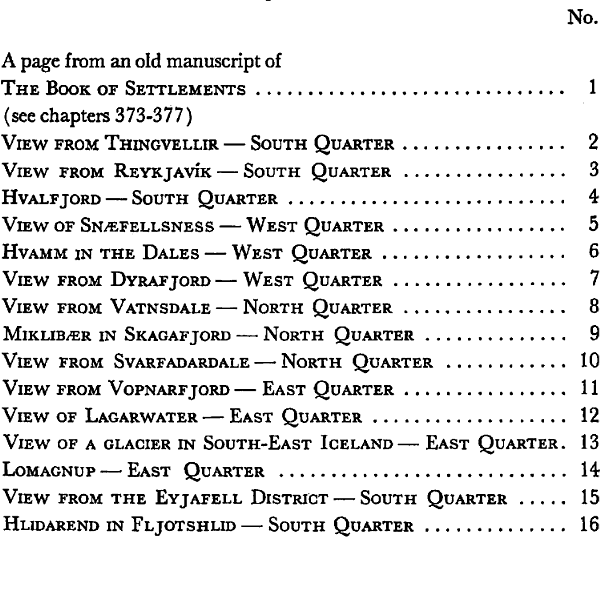

The illustrations in this edition are from photographs by Pll Jnsson and Gunnar Hannesson.

The drawing on cover and dust-jacket is reproduced with the kind permission of Haraldur J. Hamar and Heimir Hannesson, editors of Atlantica & Iceland Review.

Editors' Foreword

Up until the present time the Old Icelandic Landnmabk has been practically unknown beyond the relatively limited circle of those who possessed the ability to read Old Icelandicscholars with special philological training and Icelanders whose native language is still essentially that of their ancient forebears. It will be a source of satisfaction and pleasure to those who value this work that it is now being made available in a new translation to a wider reading public. It is hoped that this will be a public comprising not only students and scholars with a professional interest in Scandinavian antiquities, but all those whose interests encompass more than the modern world.

The world of Landnmabk still lives vibrantly in the poetry and sagas of mediaeval Iceland, a great deal of which has already been made available to the English speaking public in translation, not least of all by the admirable work of the present translators. It is most fitting, therefore, that they should now put their pen to a text about which a nineteenth century Icelandic scholar once said that the loss of this work alone would in some respects have weighed more heavily for the history of his country than of all the other sagas together.

It is the hope and intention of the editors of this volume that it should be the first and founding work in a series of publications in the field of Icelandic studies. The series will derive its homogeneity from its devotion to themes from Icelandic literature, history and culture. It is intended to present monographs and translations in both the mediaeval and modern periods and to emphasize, as far as possible, the international contexts of the subject matter.

We hereby extend our most grateful thanks to Hermann Plsson and Paul Edwards for so kindly offering the present volume to serve this purpose.

Haraldur Bessason

Robert J. Glendinnino

UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA

The Book of Settlements

Introduction

I

Iceland was the last country in Europe to become inhabited, and we know more about the beginnings and early history of Icelandic society than we do of any other in the Old World. The Book of Settlements is our chief source, tracing the discovery of Iceland by the Scandinavians and the emergence of the Icelandic nation during the Viking Period. While Scandinavian raiders were plundering in England, Scotland and Ireland, a number of farmers and peasants set sail from Norway and the Western Isles for this new land, to build a new society for themselves and their children. As late as c. 860 AD, Iceland was still an empty land, except for a few Irish anchorites driven there by viking attacks and settlements on their homeland. These Irishmen were said to have been in Iceland as far back as 795, just after the beginning of the Viking Age,1 and for the next three quarters of a century they had the country to themselves. Then, around 860, the peace was shattered by Scandinavian seafarers who seem to have gone to Iceland unintentionally, having been blown off course; and soon afterwards, perhaps about 870, the first settlers established permanent homes there. To begin with, there seems to have been a mere trickle of immigrants, but during the period c. 890-910 there was a steady stream, claiming possession of all the best farm lands. This "Age of Settlements" was over in 930 when the settlers and their sons adopted a common law for the entire country, instituted the legislative and judicial Althing, and organized their society on a new basis, by which political power was shared out between 39 chieftain-priests (goar) representing every part of the country. This was a peaceful farmers' union, based on the equality of all free men. It had no monarch, no army, no royal court. Above all, what gave it cohesion was the common law. The chieftains had judicial and legislative powers, and also priestly duties, but they depended on the support of other farmers. The highest official in the land, the Lawspeaker of the Al-thing, was elected by the chieftains, his period of office lasting three years, after which he could be re-elected for another term. The Althing met annually for a fortnight at Thingvellir to consider and change the laws and settle disputes. At the same time thirteen local assemblies were set up, one for every three chieftains. Soon after the middle of the tenth century, the country was divided into four Quartersa division reflected in the structure of the Book of Settlements and each of these had a court dealing with legal disputes between litigants of different local assemblies within the same Quarter. This political organization lasted without major changes until Iceland came under Norwegian rule in 1262-4.

1Writing about 825 in France, the Irish monk Dicuil mentions three Irish anchorites who had sailed to 'Thule' thirty years earlier. The latitude he assigns to 'Thule' makes it certain that this must have been Iceland. (Liber de mensura orbis terrae, Berlin, 1870, 42-44). The first Norwegian settlers in Iceland called these anchorites Papar, see p. 15 below.

We have already mentioned that the chieftains had certain priestly duties, but these came to an end with the adoption of Christianity by the Althing in AD 999 or 1000, and soon the Church became the most important organization in the country. The first native bishop of Iceland, Isleif Gizurarson (1056-80) laid much stress on the education of the clergy and during his term of office a number of schools were founded. His son and successor, Gizur, (1082-1118) was responsible for two important innovations: in 1097 a tithe system was set up for the whole country, and it has been suggested that this may have contributed to the first compilation of the Book of Settlements, as we shall see later. Secondly, Gizur divided the country into two bishoprics, of Holar for the North Quarter, and of Skalholt for the rest of the country. This happened in 1106, and it strengthened not only the church, but learning too. Not long afterwards, Benedictines founded the first monastery at Thingeyrar (probably about 1113), and several others, as well as Augustinian houses, were founded during the course of the twelfth century. The codification of the Icelandic laws began in 1117, and in 1127 a new church law was adopted.