EARLY BIRD BOOKS

FRESH EBOOK DEALS, DELIVERED DAILY

LOVE TO READ ?

LOVE GREAT SALES ?

GET FANTASTIC DEALS ON BESTSELLING EBOOKS

DELIVERED TO YOUR INBOX EVERY DAY!

Marine Corps

Tank Battles

in Vietnam

by

Oscar E. Gilbert

CONTENTS

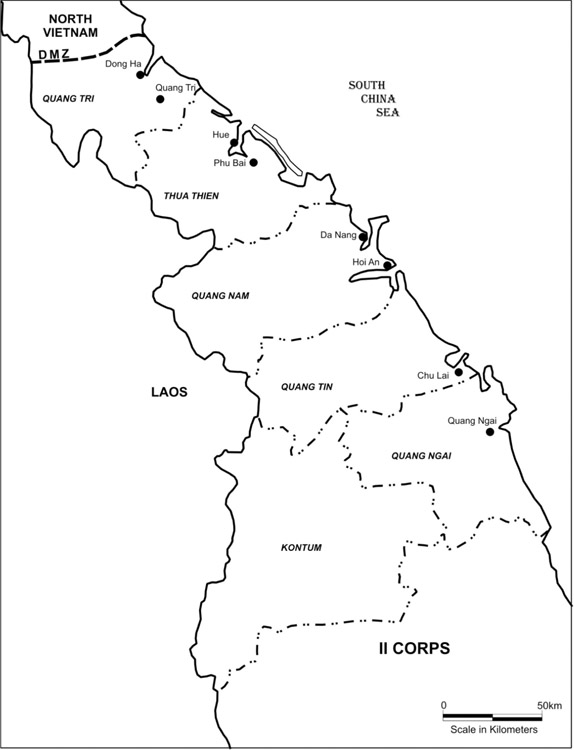

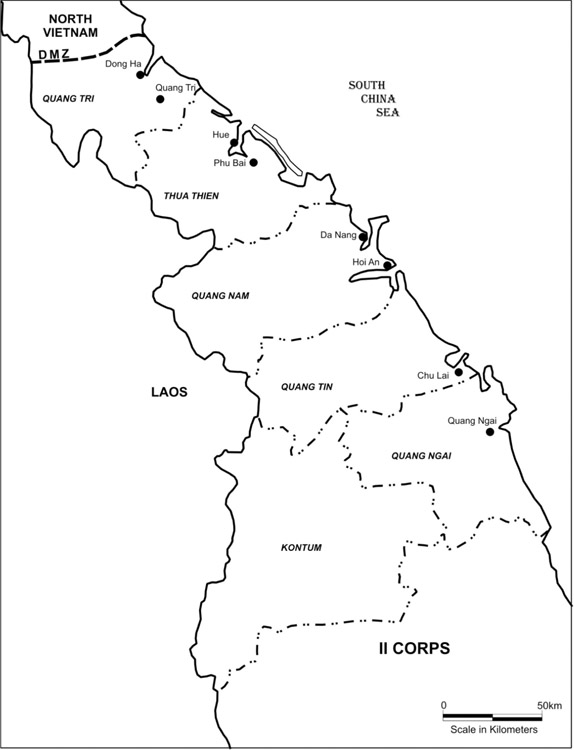

The vast bulk of Marine Corps operations in South Vietnam took place in I Corps, the northernmost sector of the country bordering the DMZ.

PREFACE:

A Complex and Undocumented War

All wars are both alike and unique. Each one is alike in that it contains that bizarre mix of horror, brutality, and waste on a massive scale that somehow brings out both the best and the worst in everyone it touches. Each war is unique in the why, where, and how it is fought, and in the way that it touches its victims. The veterans of one war may identify and sympathize with those of another, but the experience of a man who waded through the bloody tide at Tarawa alongside comrades with whom he had trained for months was vastly different from that of the man who flew to Southeast Asia on a civilian airliner to fight alongside a group of relative strangers.

Vietnam carried war to a whole other level of complexity and ambiguitymilitarily, politically and morally. There was an almost conventional war against the forces of the North Vietnamese Army, fought with artillery and maneuvering units of uniformed infantry amid a landscape almost devoid of civilians. At the other extreme was a far more personal war for the hearts and minds of a largely peasant population, where small units from both sides fought each other while intermixed with the civilians in their ancestral villages and homes.

For the individual, the war gave rise to dreadful moral ambiguities. Was a child a spy, a saboteur, or merely friendly and hungry? Was the guy who sold you a hot beer the same one who lobbed mortar rounds at you last night? Why could you pat a farmer on the back and give him a new hoe, but kill him without compunction if he wandered across an arbitrary line on a map and into a free-fire zone?

It was a war in which you could depend only upon your enemy. He would be professional, brave, tenacious, resourceful, and merciless. You could not depend upon your ally. In one day and place he might be loyal and courageous. In another time and place he might be feckless, corrupt, inept, cowardly, or even murderous if it suited his purpose of the day.

Depending upon where you were in the complex landscape it was a war fought amid shifting sand dunes, the stinking mud of rice paddies, steaming jungle, steep and stony mountains where the cold night chilled you to the bone, or all of the above.

The only clear division between how the war was experienced was geographic, with a conventional war against the NVA north of the Hai Van Pass, and a guerrilla war against the VC south of the pass. Even that distinction eventually fell away.

The nature and prosecution of military operations was far different from those of previous wars. An operation in Vietnam could be defined in any one of several ways. To the military amateur the concept of an operation is usually assumed to be some group of units undertaking a military endeavor directed toward some goal, fighting in a specific area during some defined period of time. Many operations like STARLITE and DEWEY CANYON were just such operations.

In Vietnam an operation might also be defined as any military activity within a specific geographic area. It was not unusual for a unit to be engaged in a named operation, but when it crossed some defined boundaryoften a grid line on a mapit was suddenly engaged in a different operation. Some were both, as in October 1966 when Operation PRAIRIE transitioned from an offensive field operation to an operating area.

Still other operations were thematic, defined by a specific type of activity such as COUNTY FAIR (combined civic actions and searches for local VC agents) or DECKHOUSE (amphibious raids). The Marine Corps conducted 195 such named operations, of all types, over the course of the war.

Unlike in previous wars, the Corps imitated the Army practice of creating ad hoc temporary brigades for specific operations, made up of whatever units were available. This practice allowed greater tactical flexibility, but created other problems when a battalion, company, or even a platoon was suddenly placed under an unfamiliar command structure.

Most confusing, some units in the tank battalions were simply redesignated. A platoon might be told to drive north and report to a new unit. Overnight a platoon might find itself part of a different battalion, in a different division. Small wonder that most Marines do not know to this day the names of the operations in which they participated.

Underpinning everything was the question of why America was fighting the war. It is true that there was a flawed contemporary vision of monolithic communism marching toward world dominationflawed because we could not see the nationalistic cracks in the global communist movement. The North Vietnamese under Ho Chi Minh had a clear vision of what they wanted to achieve: the forceful reunification of Vietnam. We seemed to have no overarching political counter-plan, at least not one with a clear strategy for victory. We lacked even a definition of victory. Our only definition of success was to keep the enemy from winning, and it was a recipe for failure.

The Vietnam War was unlike almost all of Americas wars in that thirty-five years after it ended the story of how, or even why, we fought it baffles historians. However, the war was very much like other wars on a more primal level. At the time the men, and a few women, who fought in Vietnam had one crystal clear vision of why they were there. It was because fate had cast them all together, eye deep in hell. They needed each other as they never would again in this world.

To add to its other ambiguities, the Vietnam War is quite poorly documented at the operational level. The common perception of the military is that they are obsessive compilers of documentation and paperwork. That much is true, and there is a form and a process for everything. Often, though, the executors of the process are nineteen-year-old clerks who dont want to be there, supervised by harried staff officers with too much to do. This alliance records everything, and then at various intervals they burn the records.

Typically the starting point for any researcher into Marine Corps operations in any conflict is the usually excellent series of official histories compiled by the Marine Corps Historical Branch. Compared to other wars, the official histories for Vietnam are strangely limited in their mention of the role of supporting arms, other than the Air Wing, which kept separate records. This is an artifact of how forces were structured, how the war was fought, and in particular it is an artifact of the unit level at which records were kept.

For both the Army and the Marine Corps in Vietnam the basic record keeping entity was the battalion. For the Marine Corps tank battalions the most useful basic records are the monthly Command Chronologies, with their intelligence summaries and numerous other sections. If you are interested in details of headquarters location, personnel and disciplinary actions, total ammunition expended, and replacement and repair of equipment, then this is the primary source.

Next page