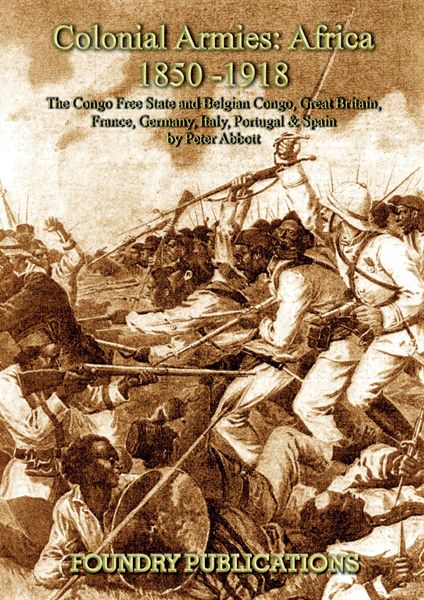

Series Editor: Ian Heath

First published in Great Britain in 2005

by Foundry Books

24-34 St. Marks Street

Nottingham

NG3 1DE

United Kingdom

Tel 0115 8414141

We are dedicated to furthering the study of all apsects of military history,

and are happy to consider suggestions for new books on

military subjects.

If you have an idea or project suitable for our list, please write to

Foundry Books Editorial Office

at the above address.

Copyright 2005 by Peter Abbott

The right of Peter Abbott to be identified as the author

of this work has been asserted in accordance

with sections 77 and 78 of the

Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 1-901543-37-4

ISBN 978-1-901543-37-7

Print ISBN: 9781901543070

Digital ISBN: 9781901543377

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may

be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior

permission in writing from the publishers.

Typeset & Digital scanning by Kevin Dallimore

0181 658 2488

Digital conversion by Kevin Dallimore

Other books by the same author:

Germanys Eastern Front Allies 194145 (with Nigel Thomas) (Osprey 1982)

Partisan Warfare 194145 (with Nigel Thomas) (Osprey 1982)

The Korean War 195053 (with Nigel Thomas) (Osprey 1986)

Modern African Wars (1): Rhodesia 196580 (with Philip Botham) (Osprey 1986)

Modern African Wars (2): Angola and Mozambique 196174 (with Manuel Ribeiro Rodrigues) (Osprey 1988)

Unknown Armies 1: British East Africa (Raider Games 1988)

Unknown Armies 2: Persia/Iran (Raider Games 1988)

Unknown Armies 3: Iraq (Imperial Press 1992)

Armies in East Africa 191418 (Osprey 2003)

CONTENTS

Colonial Armies: Africa 18501918

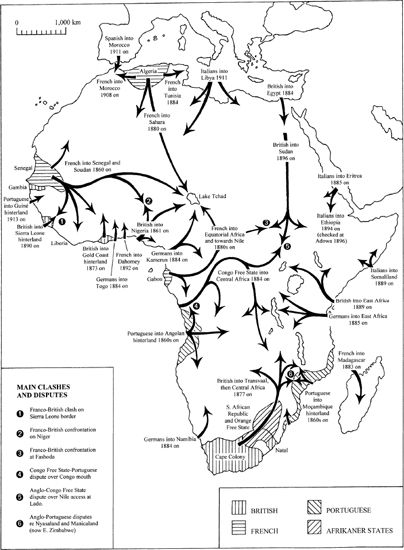

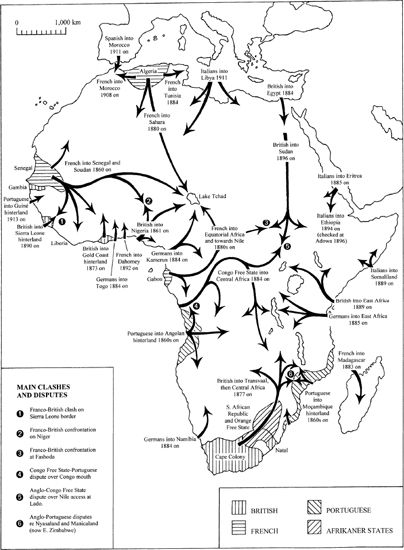

European possessions in Africa in 1850 and subsequent lines of advance. Some smaller possessions such as Ceuta and Melilla (Spain) and Ajuda (Portugal) are not shown, and the territories and routes are only approximate. Wherever possible, advances followed the courses of major rivers such as the Nile, Senegal, Niger, Congo, and Zambesi. Note that Turkey controlled Libya between 1835 and 1912, and that the Danes and Dutch had forts on the Gold Coast until they sold them to the British in 1850 and 1871 respectively.

INTRODUCTION

Africa is a big continent, larger than either North or South America and second only to Asia. The north has always been an integral part of the Mediterranean world, but the rest remained virtually unknown to outsiders. Then the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1486, sailed into the Indian Ocean, and made themselves masters of the coasts. In due course other Europeans followed. They were unable to extend their rule into the interior, however, and their settlements remained tiny, tolerated only because the local potentates benefited from the trade they brought.

All this changed in the second half of the 19th century. Suddenly, European-led columns began to fan out from their coastal footholds, smashing whatever forces could be brought against them, no matter how brave or determined the latter were. The process began at different dates in different parts of the continent, but much of it was concentrated into the 15 or so years between 1884 and 1900. By 1914 the Europeans had overrun the greater part of the continent. Remarkably, they did so without clashing with each other in the process, and conflict between them only occurred after 1914 because what was essentially a European power-struggle was projected on to the African landscape.

Although the spotlight has fallen on a few popular campaigns like the Zulu War, the armies which carried out this extraordinary conquest have seldom been surveyed as a whole, and not in the kind of organisational detail I have attempted here. This is not a diplomatic history, nor even a campaign one, but rather an attempt to describe the structure, armament, and uniforms of the colonial armies, with as much order of battle material as possible. It does not try to detail the campaigns themselves because, to be brutally honest, the superior training and weaponry of the European-led forces made most of these very one-sided. Rather, it tries to answer the question What military forces existed in Belgian, British, French, German, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish Africa in any particular year? Such years need not necessarily have seen any campaigning, although the nature of colonial warfare meant that most of them did.

I have included the First World War because this provided the real test of battle for all these forces except the Spanish (and even they had to cope with its disruptive effects). In general, the results reflected the relative military efficiencies of their European parents, but there were one or two surprises, like the high rating the Portuguese gave the Belgian colonial troops. The nastiest surprise of all, probably, was that experienced by the white South Africans, who went to East Africa confident that they would make short work of a few despised kaffirs and found themselves being taught a lesson in bush fighting by the German askaris.

The Europeans had not been able to penetrate very far into the interior until the second half of the 19th century because Africa presented formidable barriers to invasion. Much of the coastline was either desert or swamp and there were few natural harbours. The main rivers were barred by cataracts near their mouths. Endemic fevers killed off the invaders, who lacked the hard-won immunity of the native African, and the tsetse fly was equally lethal to their horses. The primitive agricultural methods used over much of the continent meant that there was little surplus food available to feed expeditions. The indigenous population was hardy and warlike, using weapons and tactics which were often better adapted to the terrain than those of the invaders. Finally, the land produced little easily exportable wealth of the kind that the early adventurers coveted. Francisco Barretos Portuguese expedition of 1571 illustrates the kind of difficulties they faced. Hearing rumours of enormously wealthy gold and silver mines, he assembled a force of would-be Conquistadors and set off into the interior of Moambique. They found no great store of precious metals there, and only a sickly remnant ever reached the coast again. Experiences like these soon showed the Europeans that Africa offered no easy road to wealth. India and the newly discovered Americas held out far better prospects. As a result, European interest in the continent soon waned, and only the profits from the infamous slave trade made it worth maintaining a limited presence on its coasts.

For something like three centuries the Africans of the interior were left to their own devices. Throughout this period there were countless wars. The slave trade undoubtedly contributed to these, but they also occurred in areas remote from its influence. Many of these conflicts were little more than glorified scrimmages, but others were savage and bloody by any standards. Some peoples were more warlike than others, but the constant threat of attack meant that all were forced to develop some sort of military system.

The typical African army was a militia in which every able-bodied man was expected to serve. In eastern and southern Africa much use was made of age regiments. Initiation ceremonies were held at regular intervals, and the youths who thus graduated together served as a kind of first-line defence force until they were replaced in due course by their successors. Elsewhere, the warriors fought together in clan or lineage groups. The Tiv of Nigeria illustrate the working of the system at its most rudimentary level. They had little or no formal political organisation, but clan members were expected to aid close relatives against more distant enemies. A familys menfolk would make their way to the battlefield, look along the fighting line for a relation, and join in beside him. In more elaborately organised states these small groups formed part of the following of a territorial chief. Each had its traditional place in the battle formation, and each man knew his allotted station. European observers unfamiliar with the African way of doing things sometimes made the mistake of thinking all was confusion and disorder. Thus a Captain Jones, commissioned to report on a Yoruba army in 1861, referred disparagingly to the irregular marching and skirmishing of the barbarous horde. However, Samuel Johnson, himself a Yoruba, explains that every man capable of bearing arms knows his right place in the army, so that what appears to be a motley crowd is really a well organised body, every man being in his right place at the front, the right or the left of his immediate chief.

Next page