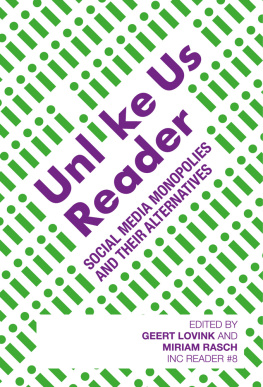

Geert Buelens - Everything to Nothing

Here you can read online Geert Buelens - Everything to Nothing full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Penguin Random House, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Everything to Nothing

- Author:

- Publisher:Penguin Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Everything to Nothing: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Everything to Nothing" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Everything to Nothing — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Everything to Nothing" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

TO NOTHING

The Poetry of the Great War, Revolution

and the Transformation of Europe

GEERT BUELENS

TRANSLATED BY

DAVID McKAY

The translation of this book was funded by the Flemish Literature Fund

(Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren flemishliterature.be)

First published in the English language by Verso 2015

Originally published as Europa Europa! Over de dichters van de Grote Oorlog

Ambo/Manteau 2008

Translation of Consolation by Anna Akhmatova Lydia Razran Stone 2012

Translation of 1917 by Carl Zuckmayer David Colmer 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-149-1 (PB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-150-7 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-151-4 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Fournier by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Press

In memoriam Alfons Buelens (18941975),

1st Caribiniers Regiment, soldier of the Great War

Chauvinism is the constant threat to the survival of humanity.

Franz Pfempfert, Die Besessenen

(The Possessed), Die Aktion, 1 August 1914

Start of the Twentieth Century

I have now seen four icebergs.

Bertrand Russell, on an ocean voyage, June 1914

Let us praise life and not shy from grand words. Let us be like the retired naval architect who, writing from London in June 1914, struck a tone commensurate with his ambitions, his spirit, and his age. His Ode Triunfal (Triumphal Ode) is a paean to modern life, an exuberant, almost erotic celebration of the sensations excited by new vehicles, machines, factories and modes of communication in the mind of one sensitive and keenly perceptive poet. No longer will he sing of chirping crickets or the foul recesses of the human heart, but of the total autonomy of modern machinery, the hitherto inconceivable pleasures of city life, and the now of a new-fashioned world that is constantly starting afresh. Ah, he sighs, how Id love to be the pander of all this!

Bathed in this metropolitan glow, even political life, crime and the media acquire an unprecedented charm. Door-to-door salesmen are no longer mere peddlers, but errant knights of industry. Nor is the poet oblivious to the birth of consumerism (O useless items everyone wants to buy). Yet in this paradise framed in flickering neon, this immediate system of the Universe, he believes that something essential is coming to light. This man is a twentieth-century counterpart of Walt Whitman (181992). The pantheism of life on wheels is his theme, the New metallic and dynamic Revelation of God a deity not benign, but utterly amoral.

This life is decidedly not without violence and danger. But why should that trouble a poet who literally has no conscience? He hails not only new construction techniques, but also advances in the arms industry, waxing rhapsodic about tanks, cannons, machine-guns, submarines, flying machines. Railway crashes, mine collapses and shipwrecks are all in the game. He compares being torn to shreds by an engine to a woman submitting to ravishment. Yes, sexuality too will be transformed: Masochism through machines is his heated cry. He spurns reason and moderation, pursuing extreme experiences without bounds or scruples. Yet in contrast to his like-minded contemporaries the Italian Futurists, he does not call for the demolition of old buildings. Instead he extols the cathedrals of Europe, confessing his fervent desire to smash his head into one and be dragged off the street, bleeding like a pig, without anyone knowing who he is.

Is this modern man? Someone whose nerves are so tightly wound that he wants them to snap on his command when the time comes? From its opening lines, this ode acknowledges the dark side of the glorious new age: By the painful light of the factorys huge electric lamps / I write in a fever. Writing appears to be a way for the poet to soothe himself, a surrogate for the aggression that he investigates and contemplates in his work:

Hi-ya-ho revolutions here, there, and everywhere,

Constitutional changes, wars, treaties, invasions,

Outcries, injustice, violence, and perhaps very soon the end,

The great invasion of yellow barbarians across Europe,

And another Sun on the new Horizon!

The poet is not unenthusiastic about the coming apocalypse, but at the same time he puts these revolutionary changes into perspective. How significant are they, really, in the light of that ageless, ever-unfolding Moment that underpins the experience of modernity? He no longer has an inner life; his only consciousness is of the outer world, where he is coupled to every train, hoisted on every dock, and spun in the propellers of every ship. Hey! Im mechanical heat and electricity! / Hey! and the railways and engine rooms and Europe! Swept up and pulled along in the seething roar, he is finally reduced to wordless cries. Man has become machine.

But then the pace slackens after all:

Z-z-z-z-z-z-z-z-z-z-z-z!

Ah if only I could be all people and all places!

He calls this a Triumphal Ode? What a farce! Its nothing but a mental trip, a futuristic thought experiment that lands, with a thud, back in reality. This man was neither a machine nor the pimp of modern life. He was not Europe, not all people and all places. Nor was his vision of catastrophe part ecstatic, part impatient entirely unique. The author of this ode, lvaro de Campos, was composing idiosyncratic variations on themes sounded elsewhere in the European avant-garde. And, despite his defiant extremism, his words betrayed a certain ambivalence. But how could it be otherwise? De Camposs life, work, views and visions issued from the protean imagination of Fernando Pessoa (18881935). These lines were written not in London but in Lisbon, at the desk of a man who rarely left the city but constructed whole worlds in his head. Pessoa took Whitmans boast, I contain multitudes, literally, publishing not only under his own name, but also under a series of heteronyms. He invented names, backgrounds and bibliographies for them, as well as opinions about literature that showed some affinity with his own, but which he could not (or dared not) unequivocally embrace. The spring of 1914 saw the birth of the serene, pagan master poet Alberto Caeiro and his two followers, the discipline-obsessed neoclassicist Ricardo Reis, and the occasionally manic Futurist lvaro de Campos. That may sound like an arbitrary cacophony of voices, but their different strategies and methods were representative of almost every major current in European intellectual life.

Pessoas poetics may appear extreme, but the deliberate ambiguity on which they were based was far from exceptional at a time when hope and despair were vying for supremacy as were the great European powers, whose Cold War style conflicts and crises in places like Morocco (in 1905, 1907 and 1911), Bosnia-Herzegovina (in 1908, 1909 and 191213) and Turkey (1911) could just barely be confined to a regional scale or warded off through diplomatic manoeuvring. The Russians and, above all, the colonial superpower of Great Britain feared the new German nation with its drive for economic and territorial expansion. The French shared this fear but were also out for vengeance, intent on reclaiming the Alsace-Lorraine region they had lost in the shameful defeat of 1870. The strikingly militaristic German state thus had so many enemies that it clung to its strong ties with AustriaHungary. But the Dual Monarchy, sunk in its own arrogance, was so despised and menaced (both its own ethnic minorities and its neighbours in Italy, the Balkans and Russia were eager to see it partly or entirely dismantled) that it seemed certain to drag Germany into armed conflict. Power centres and arsenals were being expanded, alliances forged and tested. Many people sensed that this was a historic turning point.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Everything to Nothing»

Look at similar books to Everything to Nothing. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Everything to Nothing and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.