PROHIBITION

Prohibition

A Concise History

W. J. Rorabaugh

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers

the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education

by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University

Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted

by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction

rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the

above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the

address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rorabaugh, W. J., author.

Title: Prohibition : a concise history / W. J. Rorabaugh.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2018. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017025526 (print) | LCCN 2017038948 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190689940 (updf) | ISBN 9780190689957 (epub) |

ISBN 9780190689933 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: ProhibitionUnited StatesHistory. |

TemperanceUnited StatesHistory. |

BISAC: HISTORY / United States / 20th Century.

| HISTORY / Modern / 21st Century.

Classification: LCC HV5089 (ebook) | LCC HV5089 .R667 2018 (print) |

DDC 364.1/730973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017025526

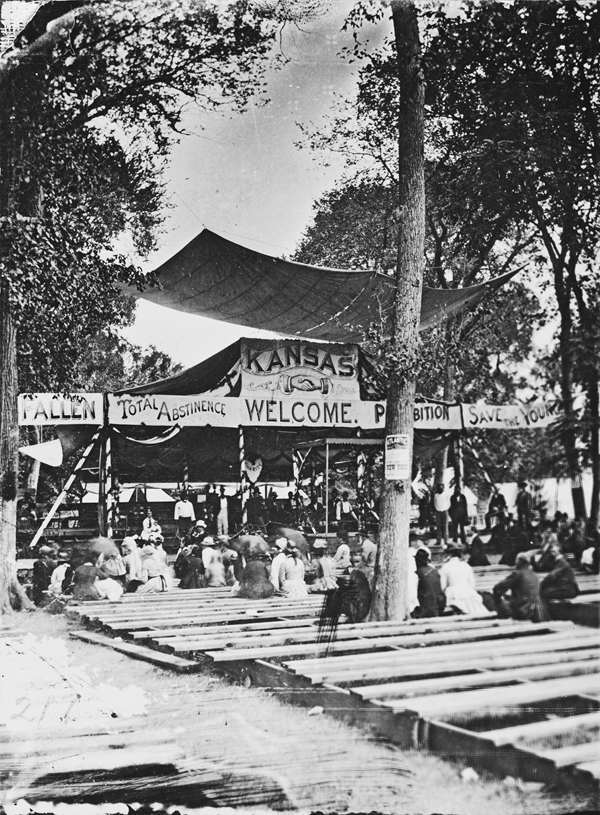

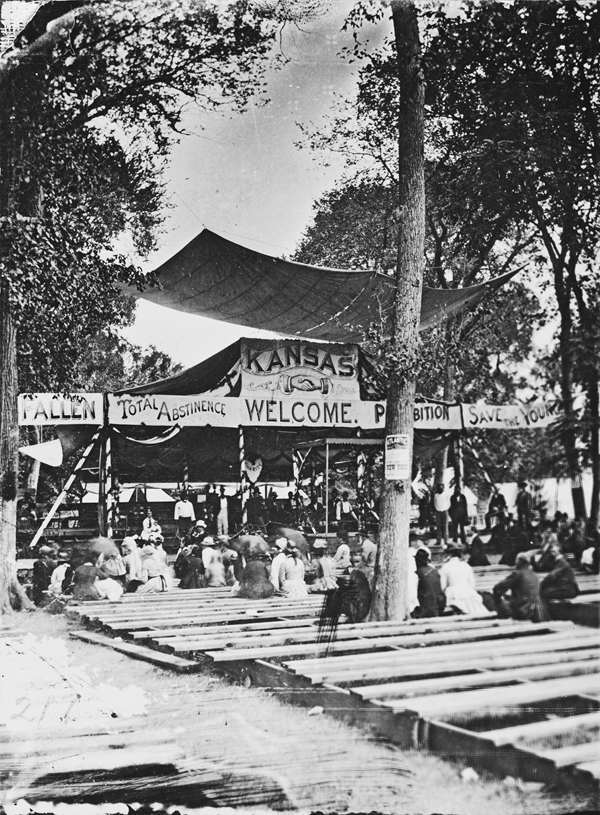

Frontispiece: At a prohibition tent revival in Bismarck Grove, Kansas, in 1878, the rural faithful rallied against the Demon Rum. kansasmemory.org, Kansas State Historical Society, 207891

CONTENTS

My curiosity about prohibition began early in life when I had to negotiate the cultural differences between my mothers wet family and my fathers dry family. During prohibition my maternal grandfather made wine in the basement from Concord grapes grown in the backyard. My mother later described the product as awful. When I was a child, my mother occasionally took a drink, but my father never did. My abstinent paternal grandfather had always declared that he would try alcohol at seventy-five. On his seventy-fifth birthday, the neighbors in the small town where he lived gathered on his front porch, knocked on the door, and presented him with a half pint of whiskey. He took one sip, set the bottle on the porch rail, muttered that he had not missed a thing, went back inside, and closed the door. His was a short drinking career.

My interest in alcohol led to The Alcoholic Republic (1979), to other research in alcohol history, and now to this short history of prohibition. I am grateful to the many scholars whose works have helped make this synthesis possible. They are cited in the notes and bibliography. Anand Yang, the chair of the History Department at the University of Washington, provided a teaching schedule that eased the writing of this book. I would like to thank Donald Critchlow and the anonymous readers for the press for their insights on earlier drafts. I am indebted to both Nancy Toff and Elizabeth Vaziri at Oxford University Press. In particular, Nancy has been a model editor at every stage of the process. For help with photographs, I would like to thank the staffs at the Denver Public Library, Indiana Historical Society, Kansas State Historical Society, Ohio Historical Society, Washington State Historical Society, and Wisconsin Historical Society.

From 1920 to 1933, the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution banned the production, sale, or transportation of alcoholic beverages. This book is about both prohibition and the century-long campaign that led to that result. The American dry movement was part of a global effort to ban or control alcohol and other drugs. This worldwide effort against pleasurable but addictive and often destructive substances began with the Enlightenment, gained strength during religious-based moral uplift and industrialization in the 1800s, and peaked after 1900 amid rising concerns about public health, family problems, and the power of producers to entice overuse. Many of these same issues belong to the war on drugs. Global trade and imperial politics have played major roles both in the spread of alcohol and other drugs and in the battle to control or stop use.

How, then, should a government handle alcohol? Can more be gained by controls or by prohibition? Sweden adopted a state control system, and Britain long used restrictive policies to reduce consumption. Although a number of nations considered a ban, only a handful have instituted one. Prohibition seldom worked the way it was intended. For example, Russian prohibition during World War I helped bring down the tsars regime.and the government lost alcohol taxes. In 1933, a disgusted country abandoned national prohibition.

This book about American prohibition addresses several related questions: How and why did one of the hardest drinking countries decide to adopt prohibition? How did a religious-based temperance movement to stop the abuse of whiskey turn into a political crusade to stop all alcohol consumption? What role did women play in this movement? How did immigration affect drinking and the campaign against alcohol? What happened during prohibition that caused Americans to change their minds? What kind of alcohol policies were adopted when prohibition ended in 1933?

The road to prohibition began with heavy drinking in colonial times. After the American Revolution, a plentiful supply of cheap untaxed whiskey made from surplus corn on the western frontier caused alcohol consumption to soar. Whiskey cost less than beer, wine, coffee, tea, or milk, and it was safer than water. By the 1820s, the average adult white male drank a half pint of whiskey a day. Liquor corrupted elections, wife beating and child abuse were common, and many crimes were committed while the perpetrator was under the influence. Serious people wondered if the republic could survive.

The growing level of alcohol abuse provoked a backlash. Reformers, rooted in the evangelical Protestant revivals of the 1820s, urged Americans to switch from whiskey to beer or light wine. Commercial beer, however, was available only in cities, and imported wine cost too much for the average drinker. Reformers then demanded that everyone voluntarily abstain from all alcoholic beverages. By 1840, perhaps half of Americans had taken the pledge, and reformers decided that the rest of the population needed to be sober, too. Beginning with Maine in 1851, eleven states passed prohibition laws during the 1850s. These laws failed in large part because Irish and German immigrants refused to give up whiskey and beer. Alcohol policy was temporarily put aside during the Civil War.

The Womans Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1874, resumed the long campaign to dry out America by fighting to ban alcohol at the local, state, and national levels. Under Frances Willard, the organization also advocated womens suffrage. Until Willards death in 1898, the WCTU was the main organization pushing anti-liquor legislation. Local option prohibition enjoyed considerable success in rural areas, where evangelical churches were strong.