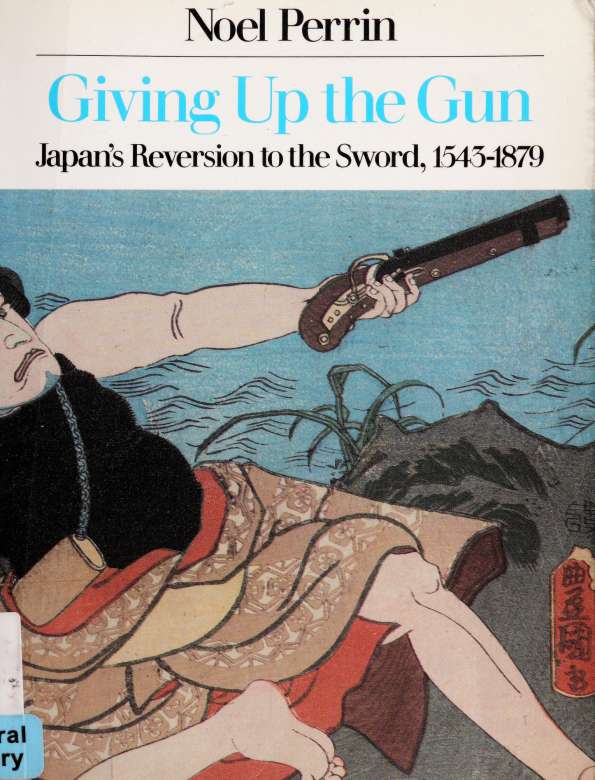

Noel Perrin - Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879

Here you can read online Noel Perrin - Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1988, publisher: David R. Godine, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879

- Author:

- Publisher:David R. Godine

- Genre:

- Year:1988

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

FOR MISHIMA YUKIO,

no pacifist, but a long-time hater of guns.

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Kahle/Austin Foundation

https://archive.org/details/givingupgunOOnoel

Alas! Can we ring the bells backward? Can we unlearn the arts that pretend to civilize and then burn the world? There is a march of science; but who shall beat the drums for its retreat?

Charles Lamb^

You can't turn back the hands of the clock.

Erie Stanley Gardner^

/ am not of course suggesting any reform; for we can no more go back from poison [gas^ to the gun than we can go back from the gun to the sword.

Lord Dunsany^

Ja" ^^'1

\

i

%

I

,1

V

V

#

FOREWORD

This book tells the story of an almost unknown incident in history. A civilized country, possessing high technology, voluntarily chose to give up an advanced military weapon and to return to a more primitive one. It chose to do this, and it succeeded. There is no exact analogy to the worlds present dilemma about nuclear weapons, but there is enough of one so that the story deserves to be far better known.

To follow the story, the reader needs to know a very little bit of Japanese history. The Japanese have had high culture and advanced technology (of a preindustrial sort) since roughly the eighth century of the Christian era. For the next 850 years the country developed completely independently of Europe, but along somewhat similar lines. It grew to be a feudal society, complete with knights in armor. Better armor, incidentally, than Europeans possessed. It had a code of chivalry. It had a complex religious establishment and many monasteries, most of them in the warlike tradition of the Knights Templar rather than the pacific tradition of the Little Brothers of St. Francis. It had great wealth. It did not have guns.^

Guns arrived in 1543, brought by the first Europeans. They were adopted at once, and were used widely for the next hun

Noel Perrin

dred years. Then they were gradually abandoned. The adoption was amply witnessed, but not the abandonment. The reason is simple. From 1543 to 1615, foreigners moved freely around Japan. First the Portuguese and then the Spanish., Dutch, and English opened trading stations. The Portuguese and Spanish (but not the Dutch and English) also attempted to convert Japan to Christianity. After some initial successes, they almost completely failed - but not before the Japanese government had become convinced that European missionaries were usually a prelude to European attempts at colonization.^ The government therefore placed a series of increasingly tight controls, first on missionaries and then on foreigners altogether. From 1616 on, free movement was at an end. The Portuguese and Spanish were required to stay within the city limits of Nagasaki; the Dutch and English were confined to the little port of Hirado.

Even these enclaves proved temporary. In 1623 the English voluntarily gave up their factory at Hirado, because they were losing money. In 1624 the Spanish were expelled from Nagasaki, because they couldnt or wouldnt control their Franciscan missionaries. In 1638 the Portuguese were also expelled. What that left in the way of foreign observers was a handful of Dutchmen. Three years later they virtually ceased to observe, because the Japanese pulled the curtain down on their window. They were not made to leave the country - the Dutch East India Company was too useful in handling trade with China - they were merely put in a kind of limbo. On May 21, 1641, the Dutch were required to give up their shipyards and foundries at Hirado and move to a tiny artificial island in Nagasaki harbor, called De-shima. It was about two hundred yards long by eighty yards wide: just over three acres.

With one annual exception, the Dutch merchants who lived on the island were not allowed to set foot on the mainland, nor were they encouraged to learn Japanese. They saw little and

X

Giving Up the Gun

understood less of what went on in Japan during the next two centuries.^ Certainly they did not understand what happened about guns.

When the first Europeans arrived, Japan consisted of several hundred semi-independent principalities. (The early Europeans regularly referred to the daimyo who ruled these principalities as kings.) Technically, all of them were subservient to the emperor in Kyoto but the mikados rule was even more of a fiction than that of the Holy Roman Emperor in Germany.

These principalities were almost continuously at war with each other during the first sixty years that Europeans were allowed in Japan. But during that time, three of the most famous leaders Japan has ever had gradually unified the country. These men were Lord Oda Nobunaga, who began the process; Lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who all but completed it; and Lord Toku-gawa leyasu,^ who established in 1600 a stable dynasty that lasted until 1867. (Still, of course, technically subservient to the emperor.) Some years before the Tokugawas fell, Japan had been forcibly reopened to foreign trade and foreign technology

* These names are backward by Western standards. In Japan the family name comes first, and what we call the first name comes last. Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa are surnames; Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and leyasu are first names. But though this is the practice in Japan itself, since 1868 there has been a gradual though never complete conversion to Western name-order for use outside Japan. Japanese first and last names looking much alike to Western eyes, the possibilities for confusion are numerous.

In this book I have followed a simple rule. All Japanese names in the text are family-name-first, even those of the one or two people who lived after 1868. The same is true in the narrative part of footnotes. In book citations and in the bibliography, however, I have followed the standard Western form. In a citation to Junji Homma, The Japanese Sword^^ Junji is the authors first name, Homma his last.

XI

Noel Perrin

... and at that point my brief account can cease. Japans subsequent history is more or less well known in the V/est, if not always correctly interpreted.

One final note. The principal European observers in sixteenth-century Japan were Jesuit missionaries, sent by Portugal. Some of them were very capable observers indeed. They read and spoke Japanese with ease, they were highly educated, they were careful and accurate. But they naturally tended to stress religious matters, and to pay relatively little attention to military technology - beyond observing with disgust that their Japanese counterparts, the Buddhist monks, were keen swordsmen and, for a time, formidable users of guns.- So even for the period from 1543 to 1615, European accounts tend to be brief and vague on matters of war, full and precise on the number of Christian converts in Owari, the kinds of restrictions placed on missionaries in Kyoto. This is one reason why even now, in the Western memory of that period in Japan, there is general awareness of the expulsion of Christianity, and almost no awareness of either the rise or the abandonment of firearms.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879»

Look at similar books to Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Giving Up the Gun: Japan’s Reversion to the Sword, 1545-1879 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.