Q uick question: Was George Washington straight?

Umm... yeah?

Most of us have probably never considered our first presidents sexual identity beyond knowing that he was married to a woman. We just assume he was straight because history doesnt explicitly tell us otherwise. But when we make assumptions about any historical figure, we rewrite the past without even knowing it. What other assumptions are we making about the gender identities and sexualities of historical figures we think we know? And how do those assumptions shape the way we see the pastand our present?

The version of history we learn in school puts a straight, cisgender mask on almost everyone. But the truth is, queer people have been part of history throughout every era, on every continent. Being queer isnt new; queer people have existed for as long as people have existed! And acknowledging that fact does something major: it reminds those who identify as queer that they have proud queer ancestors who fought for their rights, that they have cultural grandparents who took a stand. No one is alone in being queer, and shedding light on past queer identities can help us dig for the whole story on any number of historical figures. Recognizing the worlds rich history of queerness helps reduce homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia, and helps welcome queer identities to the mainstream with love and acceptance. Thats important, not only for queer people but for anyone who feels left out of or incapable of relating to the popular version of history most of us know.

QUEER...

What do we mean when we say queer? The word means so many different things to different people, and its definition is changing all the time. For some, its still a painful and derogatory term; for others, its been reclaimed. For the purpose of this book, queer means anyone not totally straight or not totally cisgenderanyone outside societys gender and sexuality norms. Queer in this book does not only equal gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender (terms often lumped together in the abbreviation LGBT or GLBT). Those four words refer to specific modern identity labels, and only a few of them at that. Queer also includes labels like genderqueer, panromantic, and asexual, as well as identities of people who showed characteristics of queerness (like gender nonconforming or same-sex loving) before we had any labels for them. A lot of these words and constructions didnt even exist a couple hundred years ago. Seriously: the words heterosexual and homosexual werent invented until 1869. But of course people of the same sex were into each other, dated, had sex with each other, and loved each other before the 1860s. They have done those things since forever. But putting present labels on past actions is tricky, which is why you need to choose your words wisely. (For more information about different queer terms, check out the glossary in the back of the book.)

So: the language we bring to the exploration of queer history is obviously as complex as the history itself. Were leaving out hundreds, if not thousands, of terms for different kinds of queerness just by focusing on the words we have in the English language. (For instance, around the globe there have been entire minilanguages used exclusively by queer people, like Polari in Britain and Gayle in South Africa.) In English, all language related to queerness was initially more focused on actual sex acts than on a sense of self. One early example is the word sodomite, which means a person who commits the crime of sodomy. Sodomy comes from the Bible, specifically the town of Sodom, which was synonymous with violence and cruelty, including, in one story, an instance of attempted same-sex rape. Sodomy was used to describe men having sex with men and then, natch, used to outlaw men having sex with men. Since self-identifying as gay wasnt yet a thing, it was doing the sex act itself rather than being homosexual that was illegal.

When a new sense of personal identity began to form around same-sex sexual attractions, language expanded accordingly. Uranian was used in 1800s Europe to mean men with female spirits, and the word bisexual was also coined around the same time. (Previously, no English word had existed to describe a person sexually attracted to more than one gender!) Then, through most of the 1900s in Europe and North America, people with any kind of same-sex attraction were labeled homosexual, without any room for identity complexity. Fast-forward to 1950s and 1960s North America, where there was a popular movement to adopt the term homophiles instead of homosexuals, placing the emphasis on same-sex love instead of sex. Obviously, that didnt stick.

As for the ladies, we currently use lesbian to describe women attracted to other women. The term means from Lesbos, the Greek island where the poet Sappho wrote about loving other women in the 600s BCE, though the word took on its current connotation centuries later. (Fun fact: The citizens of Lesbos, the original Lesbians, unsuccessfully sued the Homosexual and Lesbian Community of Greece in 2008 for people to stop using that word to mean gay women.) Tribade (referring to tribadism, an old word for scissoring) and sapphist (theres Sappho again) were used before lesbian was popularized.

And for the trans and gender nonconforming folks out there, Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term transvestite in 1910 (more on Magnus later). Cross-dresser was also common back then and was used more broadly than it is today. In the 1970s a bunch of words like transgenderal, transgenderous, and transgenderist were tried out before transgender was generally settled upon. One of the earliest words used to describe intersex people, hermaphrodite (now a slur but once the preferred term), came from the god Hermaphroditos, who in mythology blended with a nymph to become one being of two genders.

The language we use to describe peoples identities matters; these words have a great deal of power. There are literally hundreds of ways to describe queerness in English aloneand its important to respect the exact terms a person uses to self-identify. For gender pronouns in the chapters to come, weve made case-by-case decisions in an effort to respect how individuals described themselves; and youll see in one story that we chose the gender-neutral they instead of he or she. In a few stories we also used the birth name of a person who later transitioned to using another name; in modern times, its almost always considered hurtful and rude to bring up a transgender persons birth name, and we only did it here either because that person used both names to describe themselves even after transitioning, or for historical clarity when unavoidable.

THERE...

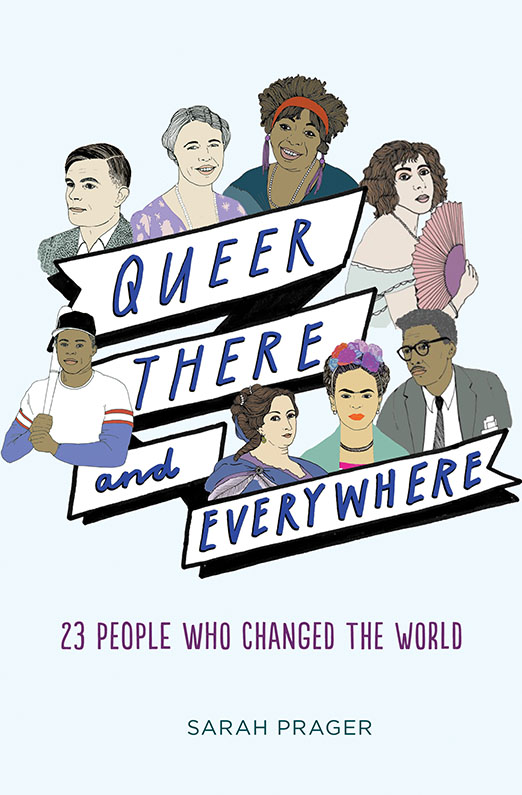

There has been no time in human history when queer genders and sexualities didnt exist. From aboriginal Australia to Japanese folk culture to American slave plantations, people of all faiths, races, heritages, and cultures have been queerevery color of the rainbow and then some. Some of the individuals featured in the chapters ahead illustrate a few of the many different ways people have transgressed gender and sexuality norms throughout time. Others are historymakers youve heard of, but who you might not have realized had a queer side. And still others are the activists who shaped the queer rights movement thats ongoing today. Each one of them is a part of the story.

But before you get the lowdown on these twenty-three incredible individuals, its important to have all the context. What was going on around the world, and in their local communities, while each of them was alive? What strides had the queer rights movement already made? Global cultures have demonstrated various levels of queer acceptanceand intolerancethroughout history. For those cultures that did embrace diversity, tolerance became a lot harder when Christian European colonists conquered almost every corner of the globe in the fifteenth to twentieth centuries. Suddenly there was exactly one correct way to do gender and sex almost everywhere. Sure, some places maintained their unique structures, like the Bugis in Indonesia (who still have five genders instead of two), but the world overall had far fewer rainbow colors. A rise in the persecution of queer people can be linked to the rise of Christianity, though Christianity is certainly not the only religion to question the morality of queer identities and sexualities. The story of worldwide queerness is being written and rewritten across the globe every day, as mainstream attitudes change and understanding grows.