A SECRET MEETING

he sun is a cold star. Its heart, spines of ice. Its light, unforgiving. In February, the trees are dead, the river petrified, as if the springs had stopped spewing water and the sea could swallow no more. Time stands still. In the morning, not a sound, not even birdsong. Then an automobile, and another, and suddenly footsteps, unseen silhouettes. The play is about to begin, but the curtain wont rise.

he sun is a cold star. Its heart, spines of ice. Its light, unforgiving. In February, the trees are dead, the river petrified, as if the springs had stopped spewing water and the sea could swallow no more. Time stands still. In the morning, not a sound, not even birdsong. Then an automobile, and another, and suddenly footsteps, unseen silhouettes. The play is about to begin, but the curtain wont rise.

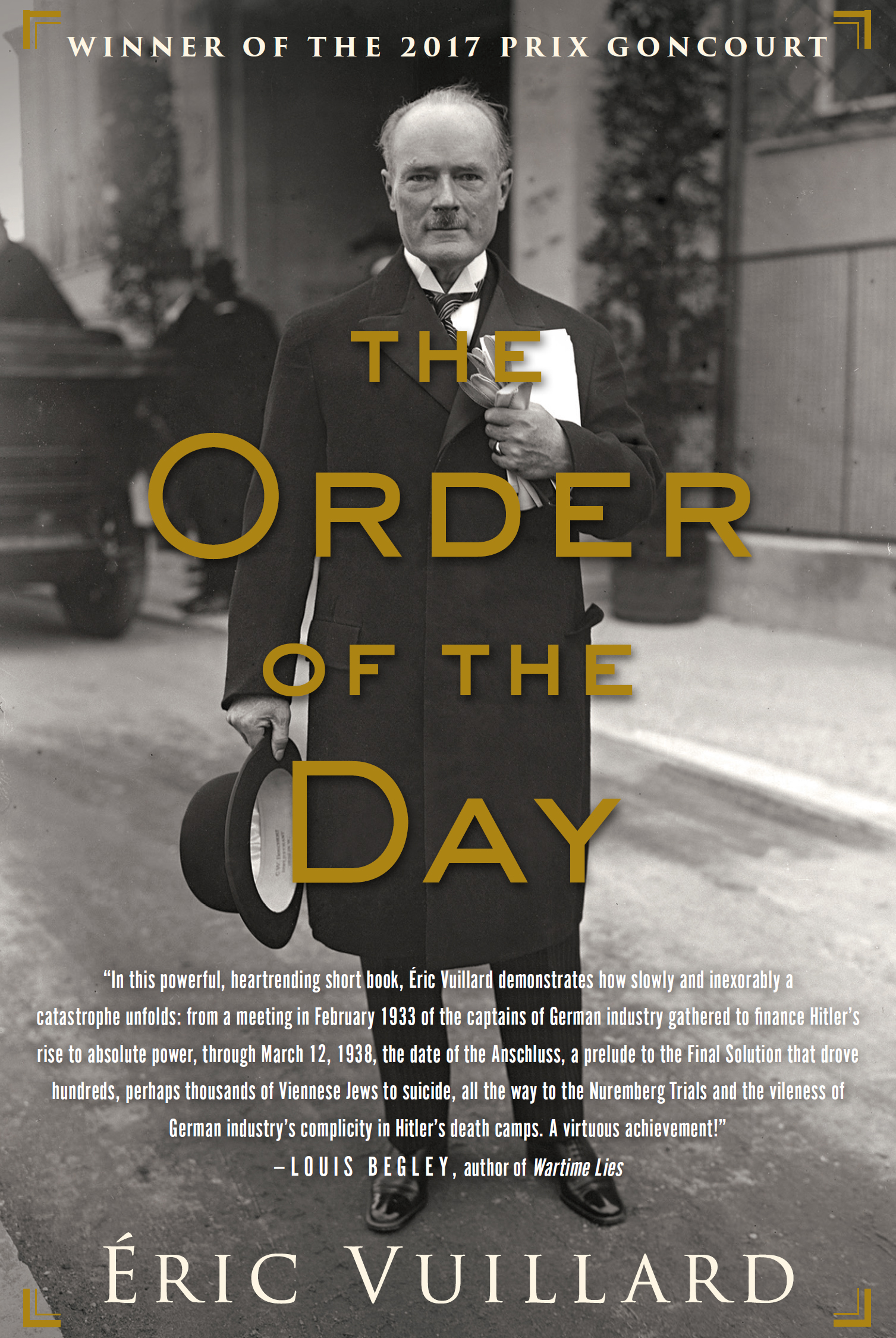

Its Monday. The city is just beginning to stir behind its scrim of fog. People go to work as on any other day; they board the bus or trolley, thread their way onto the upper deck, then daydream in the chill. And even though the twentieth of February 1933 was not just any other day, most people spent the morning grinding away, immersed in the great, decent fallacy of work, with its small gestures that enfold a silent, conventional truth and reduce the entire epic of our lives to a diligent pantomime. The day passed, quiet and normal. And while everyone shuttled between house and factory, market and courtyard where the laundry is hung out to dry, or in the evening between office and tavern, before finally heading homefar away, far from the decent labors, far from domestic life, on the banks of the Spree, some men got out of their cars in front of a palace. Through doors obsequiously held open, they stepped from their huge black sedans and paraded in single file, dwarfed by the heavy sandstone columns.

There were twenty-four of them, near the dead trees on the bank: twenty-four overcoats in black, brown, or amber; twenty-four pairs of wool-padded shoulders; twenty-four three-piece suits, and the same number of pleated trousers with wide cuffs. The shadows entered the large vestibule of the palace of the President of the Assemblythough before long, there would be no more assembly, no more president, and eventually no more parliament. Only a heap of smoking rubble.

For now, they doffed twenty-four felt hats and uncovered twenty-four bald pates or crowns of white hair. They shook hands solemnly before mounting the stage. The venerable patricians stood in the huge vestibule, exchanging casual, respectable banter, as if at the starchy opening of a garden party.

The twenty-four silhouettes conscientiously took a first stairway, then trudged up another flight, step after step, occasionally halting so as not to overtax their old hearts. They climbed, hands gripping the copper rail, eyes half-shut, without admiring the elegant banister or the vaulting, as if on a heap of invisible dead leaves. At the narrow entrance, they were ushered to the right; and there, after several paces over the checkered tiles, they scaled the thirty steps leading to the third floor. I dont know who was first in line, and ultimately it doesnt matter: all twenty-four had to do exactly the same thing, follow the same path, turn right around the stairwell, until finally, on their left, they entered the salon through the wide-open doors.

They say that literature gives you license. So I could, for instance, make them turn around the Penrose stairs in perpetuity, going neither up nor down, or both at the same time. And indeed, thats pretty much the sense we get from books. The time of wordscompact or fluid, dense or impenetrable, stretched out, granularhalts movement and leaves us mesmerized. Our heroes are in the palace for all eternity, as if in an enchanted castle. They are thunderstruck from the outset, petrified, frozen. The doors are simultaneously open and shut, the fanlights worn, dangling, smashed, or repainted. The stairwell gleams, but it is empty; the chandelier sparkles, but it is dead. We are everywhere in time. And so, Albert Vgler climbed the steps to the first landing, and there he raised his hand to his detachable collar, sweating, dripping with perspiration, feeling slightly dizzy. Beneath the large gilded lantern that lit the flights of stairs, he straightened his vest, undid a button, loosened his collar. Perhaps Gustav Krupp paused on the landing as well, giving Albert a compassionate word, a small apothegm on old ageshowed a little solidarity, in short. Then Gustav went on his way and Albert Vgler remained there a few moments longer, alone beneath the chandelier: a huge, gold-plated vegetable with an enormous ball of light in the center.

Finally, they entered the small salon. Wolf-Dietrich, private secretary to Carl von Siemens, dawdled for a moment near the French windows, letting his eyes linger on the thin coat of frost dusting the balcony. For a moment he escaped from the petty intrigues of this world, borne on cotton wool. And while the others chitchatted and puffed on their Montecristos, jabbering about the cream or taupe color of the wrappers and whether they liked their cigars smooth or spiced (though all of them were partial to fat ring gauges), absently squeezing the fine gold bandswhile all of this was happening, Wolf-Dietrich stood daydreaming at the window, wavering with the bare branches and floating above the Spree.

A few steps away, admiring the delicate plaster figurines decorating the ceiling, Wilhelm von Opel raised and lowered his thick round glasses. His family was among those that had risen over the generations, going, through promotions and accumulations of estates and grandiose titles, from small landowners around the municipality of Braubach to magistrates, then burgomasters, until Adam Opelissued from his mothers indecipherable entrails and schooled in the tricks of the locksmiths tradedesigned a marvelous sewing machine that marked the true onset of their glory. In reality, Adam invented nothing. He got himself hired by a manufacturer, kept a low profile, then made a few improvements. He married Sophie Scheller, who brought with her a substantial dowry, and named his first sewing machine after her. At that point, production soared. It took only a few years for the sewing machine to realize its potential, enter the mainstream, become part of everyday life. Its true inventors had come along too early. Once the success of his sewing machines was a fait accompli, Adam Opel branched off into velocipedes. But one night, a strange voice slipped through the half-open door. His heart felt cold, so cold. It wasnt the sewing machines actual inventors come to beg for royalties, or his workers demanding their share of the profits. It was God claiming his soul: he had to give it back.

he sun is a cold star. Its heart, spines of ice. Its light, unforgiving. In February, the trees are dead, the river petrified, as if the springs had stopped spewing water and the sea could swallow no more. Time stands still. In the morning, not a sound, not even birdsong. Then an automobile, and another, and suddenly footsteps, unseen silhouettes. The play is about to begin, but the curtain wont rise.

he sun is a cold star. Its heart, spines of ice. Its light, unforgiving. In February, the trees are dead, the river petrified, as if the springs had stopped spewing water and the sea could swallow no more. Time stands still. In the morning, not a sound, not even birdsong. Then an automobile, and another, and suddenly footsteps, unseen silhouettes. The play is about to begin, but the curtain wont rise.