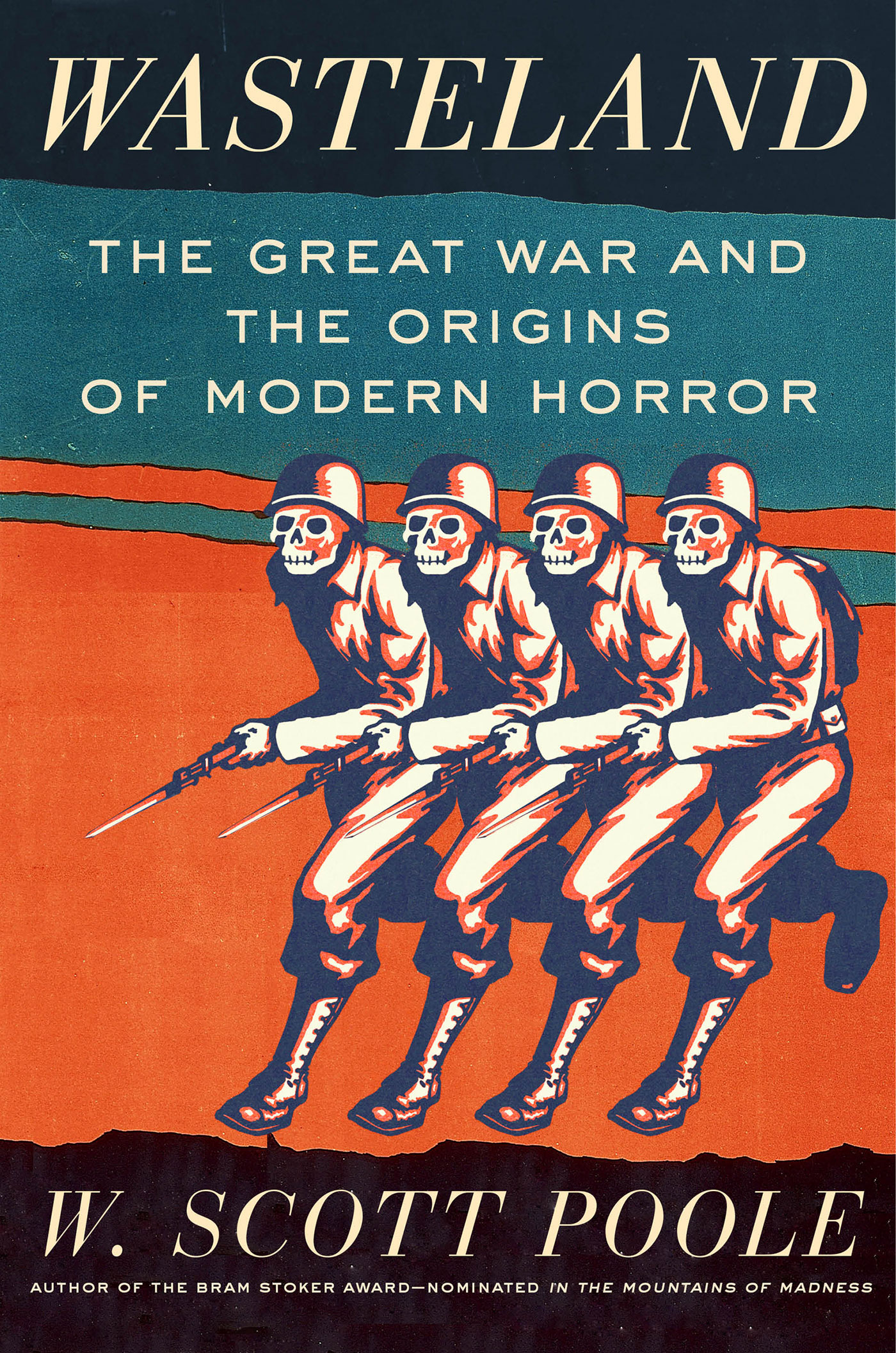

WASTELAND

ALSO BY W. SCOTT POOLE

In the Mountains of Madness

The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of H. P. Lovecraft

Vampira

Dark Goddess of Horror

Monsters in America

Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting

Satan in America

The Devil We Know

South Carolinas Civil War

A Narrative History

Never Surrender

Confederate Memory and Conservatism in the South Carolina Upcountry

WASTELAND

Copyright 2018 by W. Scott Poole

First hardcover edition: 2018

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

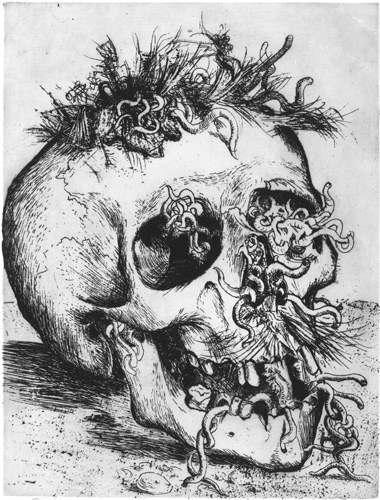

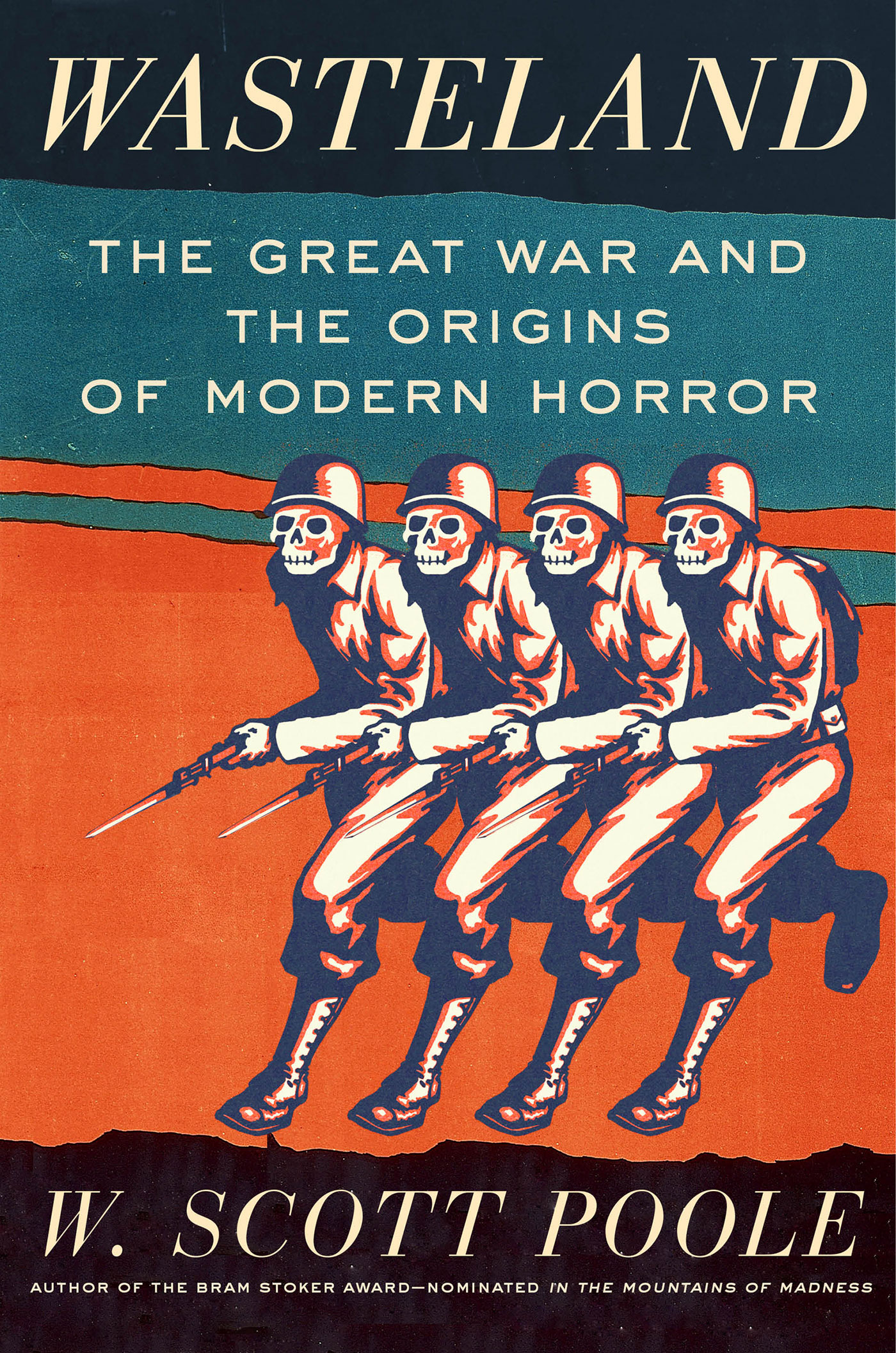

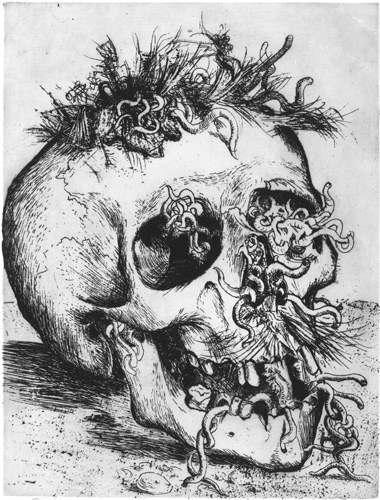

Frontispiece: Skull by Otto Dix The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Poole, W. Scott, 1971 author.

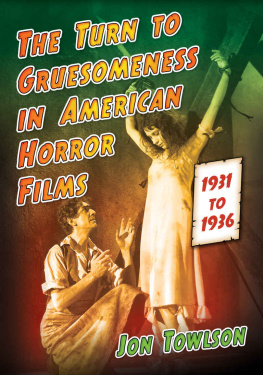

Title: Wasteland : the Great War and the origins of modern horror / W. Scott Poole.

Description: First hardcover edition. | Berkeley, California : Counterpoint :

Distributed by Publishers Group West, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018021078 | ISBN 9781640090934 | eISBN 9781640090941

Subjects: LCSH: Horror filmsHistory and criticism. | Horror in literatureHistory. | Horror in artHistory. | Psychic trauma

History. | World War, 19141918Influence. | War and society

History20th century. | Civilization, Modern20th century.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.H6 P64 2018 | DDC 791.43/6164dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018021078

Jacket design by Jaya Micelli

Book design by Wah-Ming Chang

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Beth

War broke: and now the Winter of the world

WILFRED OWEN , 1914 (1914)

The Wasteland grows; woe to those who cannot see the wasteland within.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE , Thus Spake Zarathustra (1891),

used as an epigram by painter Otto Dix

for Seven Deadly Sins (1933)

And still they come and go and this is all I know

That from the gloom I watch an endless picture show.

SIEGFRIED SASSOON , Picture Show (1919)

C ONTENTS

WASTELAND

Foreword

Corpses in the Wasteland

There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.

WALTER BENJAMIN

Writing history seems mostly the preoccupation of dwellers among ruins. The Great War (19141918) represents the literal and figurative ruins of the twentieth century, the years that caused the sense of exuberance born in the nineteenth century to sicken and sour. In much of Europe, the sheer number of the dead swept away a century of sentimental mourning practices in a matter of months. The war remade the worlds map, created new global powers, and brought with these changes some of the seemingly intractable, and possibly apocalyptic, problems in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Russia that appear to us in every days news feed.

Behind the words of the freewheeling intellectual and essayist Walter Benjamin, a man who wandered across the broken Europe of the 1920s and 30s until it became his death, lay another truth. What we admire and love in our cultureboth high culture and pop culture, and even what Mark Dery calls unpopular culturehides a world of suffering. Everything produced by civilization has written into it the viral code of barbarism. In every horror movie we see, every horror story we read, every horror-based video game we play, the phantoms of the Great War skittle and scratch just beyond the door of our consciousness. Numberless dead and wounded bodies appear on our screens, documents of barbarism coauthored by the Great War generation and all the forces that have fed off them in the decades since.

The world before 1914, just a little over a hundred years ago, seems unrecognizable today. It was a world of creaky empires that had hobbled from the Middle Ages into the modern worldRussia, Hapsburg Austria, the Ottoman Empire. All of them welded together peoples and language groups with little or nothing in common. After the final defeat of Napoleon in 1815, many crowned heads thought the mighty jinn of revolution had been placed firmly back in its prison. Kaisers, emperors, and kings fought short conflicts, made marriage alliances, and negotiated treaties in exchange for tiny territories. Scrappy Great Britainwith its constitutional monarchy, muscular industrial revolution, large middle class, and unmatched sea powerruled an empire that stretched from the Caribbean to Africa to Asia. America seemed an upstart with a tiny army and territorial ambitions focused on Latin America and the Pacific, regions that had attracted only limited attention among the old European powers.

Signs appeared that this world might crumble. The inability to consider all the ramifications of these signs helps explain why Europes political culture decided to turn the Old World into flaming wreckage. The Serbian people of the Balkans had developed enormous national pride and grounded it in a partially fictionalized history. They had no interest in becoming another principality of the Hapsburg Empire. The burgeoning economies in western Europe depended more and more on the markets and materials of their colonial possessions, without which they feared economic ruin at home. Russia lost a war in 1905 to Japan, and suddenly a new power appeared on the world stage, one that constituted an utter riddle to most in the West despite its long and fascinating history. The United States had also won a war against Spain, a seemingly decrepit European power. Wars like the short but bloody Crimean conflict and the protracted American Civil War suggested that changes in technology could now kill in the tens of thousands while leaving whole generations scarred and wounded. But a tenuous peace existed while nations and empires played with whole populations as if they were chess pieces. The gamesmanship of the old powers of Europe rigged up a complicated system of alliances, tethered to one another in such a way that one falling into the abyss would drag all the others with it.

In the summer of 1914, the coming of the conflict that at first saw Germany and Austria-Hungary (the Central Powers) fighting against France, Britain, Russia, and Serbia (the Allies) caused an eerie joy to come to the romantically inclined. In this book, we will watch writers and artists and actors and early film directors joining artillery companies, machine gun units, and the infantry. Many, though certainly not all, Europeans spoke of the conflict as an adventure, and probably a short-lived one, in which the grinding routine of daily life would give way to the lan of conflict. Everyone expected to return home a hero. Like a storm breaking the monotony of a hot, dry day, the dark clouds of war thundered across the landscape while a vital rain poured down.

In only a few short weeks, however, horror replaced the so-called war fever of the summer. On the western front, Germany swept through Belgium. German troops came within eighteen miles of Paris, causing at least one million of the citys three million inhabitants to flee. British and French troops fought back the Germans at the Battle of the Marne, but both sides suffered catastrophic losses. Fifteen thousand British soldiers died in just two weeks of fighting. In the east, czarist Russia had some early successes against Austria-Hungary and Germany, invading East Prussia. At the Battle of Tannenberg in August, a relatively small German army under Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff handed the Russian Empire a defeat from which it never fully recovered. The fighting enveloped eastern Europein Bulgaria, which fought alongside the Central Powers; in Serbia and Romania, both joined to the Allies.

Next page

![Matt Cardin - Horror Literature Through History [2 Volumes]: An Encyclopedia of the Stories That Speak to Our Deepest Fears](/uploads/posts/book/119545/thumbs/matt-cardin-horror-literature-through-history-2.jpg)