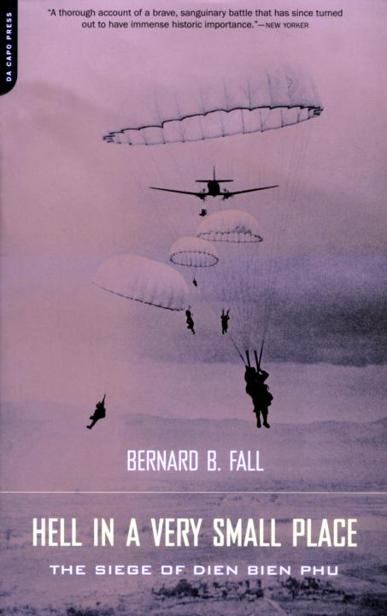

BERNARD B. FALL

To Dorothy

who lived with the ghosts of Dien Bien Phu for three long years

THERE HAVE been, even in recent history, many sieges which lasted longer than the French Union garrison's defense of a small town in the northeastern corner of Viet-Nam with the unlikely name of "Seat of the Border County Prefecture," or, in Vietnamese, Dien Bien Phu.

The French reoccupation of the valley lasted a total of 209 days, and the actual siege 56 days. The Germans held Stalingrad for 76 days, while the Americans held Bataan for 66 days and Corregidor for 26; British and Commonwealth troops defended Tobruk once for 241 days. The record World War II siege was no doubt that of the French coastal fortress of Lorient, held by German troops for 270 days from 1944 until VE-day. Many of the major sieges of recent years involved large numbers of troops on both sides: there were 330,000 German troops encircled at Stalingrad at the beginning of the siege, and the Soviet troops which encircled them numbered over one million. In comparison, Dien Bien Phu, with a garrison which barely exceeded 13,000 men at any one moment, and a Viet-Minh siege force totaling 49,500 combatants and 55,000 support troops, could hardly qualify as a major battle, let alone a decisive one.

Yet that is exactly what it was, and in a way which makes it one of the truly decisive battles of the twentieth century-in the same sense that the First Battle of the Marne, Stalingrad, and Midway were decisive in their times: although hostilities continued after the particular battle-sometimes for years-the whole "tone" of the conflict, as it were, had changed. One of the sides in the conflict had lost its chance of attaining whatever it had sought to gain in fighting the war.

This was true for the French after they had lost the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. The French Indochina War had dragged on indecisively since December 19, 1946, and reluctantly-far too reluctantly to derive any political or psychological benefit from the gesture-the French granted the non-Communist regime of ex-emperor Bao Dai some of the appurtenances but little of the reality of national independence. In fact, as the war bit deeper into the vitals of the French,professional army and consumed an ever-rising amount of France's postwar treasure (it finally

It is because the United States herself now takes precisely that latter position that Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara went to Paris in December, 1965, to plead for greater and more direct support by America's NATO allies in the struggle the United States has been shouldering almost exclusively (with the exception of the South Vietnamese Army and minor contingents from a few small nations). The results, apparently, were negligible.

In contrast to the United States, France never had the strength for a large-scale unilateral commitment, and knew that public opinion at home, as well as war weariness among the nationals upon whose territory the war was being fought (a factor that appears to be too often forgotten now), demanded that a short-range solution to the conflict be found. Or, barring victory, that a situation be created in which the national armies of the Associated States of Cambodia, Laos, and Viet-Nam could deal with Communist guerrilla remnants once the French regulars had destroyed the enemy's main battle forces in a series of major engagements.

Contrary also to the American Chief Executive who is able to commit American troops in unlimited numbers in undeclared overseas wars, the French Parliament, by an amendment to the Budget Law of 1950, restricted the use of draftees to French "homeland" territory (i.e., France and Algeria, and the French-occupied areas of Germany), thus severely limiting the number of troops that could be made available to the Indochina theater of operations. Caught in a web of conflicting commitments and priorities-NATO and communism in Europe vs. containment in a peripheral area of Asia-the ever-changing governments of the French Fourth Republic shortchanged all of them : the French units in Europe, gutted of the bulk of their regular cadres, were unusable in the event of war, and the regulars sent to Indochina were scarcely more than skeleton units to be hastily brought up to strength by locally recruited troops. When General Navarre, upon assuming command in May, 1953, requested 12 infantry battalions and various supporting units, along with 750 more officers and 2,550 noncommissioned officers for his already understrength units, he finally received 8 battalions, 320 officers and 200 noncommissioned officers-and was told that the "reinforcements" were in fact an advance on the replacements he would have received the following year for 1953 combat losses.

In the meantime, the enemy was getting stronger by the day, particularly in well-trained, regular combat divisions that could take on anything the French could oppose them with. Twelve years later, the North Vietnamese were still unafraid to take on the best forces the United States can muster. With the Korean war terminated in a stalemate in July, 1953, Chinese instructors and Chinese-provided Russian and American equipment began to arrive in North Viet-Nam en masse. The enemy now had seven mobile divisions and one full-fledged artillery division. and more were likely to come rapidly from the Chinese divisional training camps near Ching-Hsi and Nanning. It therefore became imperative for the French to destroy at least a large part of the enemy's main battle force as rapidly as possible. This was feasible only if the French could induce the enemy to face up to them in a set-piece battle, by offering the Viet-Minh a target sufficiently tempting to pounce at, but sufficiently strong to resist the onslaught once it came. It was an incredible gamble, for upon its success hinged not only the fate of the French forces in Indochina and France's political role in Southeast Asia, but the survival of Viet-Nam as a non-Communist state and, to a certain extent, that of Laos and Cambodia as well-and perhaps (depending on the extent to which one accepts the "falling dominoes" theory) the survival of some sort of residual Western presence in the vast mainland area between Calcutta, Singapore, and Hong Kong.

This book is the history of that gamble. When the general editor for the Great Battles Series, the eminent military historian and writer Hanson W. Baldwin, approached me in 1962 with the assignment, I undertook it with great trepidation. I realized, from previous research on far less sensitive aspects of the Indochina War, that it would be extremely difficult to piece together a reasonably accurate picture of what actually happened at Dien Bien Phu without access to the existing military archives. A perusal of the available literature, with its obvious contradictions and errors, only increased my concern. In presenting the French authorities with my request for access to the documentation, I emphasized that any scientifically accurate account of what actually occurred at Dien Bien Phu would hardly constitute a complimentary picture of French political or military leadership in the Far East at that time. But, I argued, the myths and misinformation that had hardened into "fact" over the years would not only distort history irremediably but also prevent others who have a more immediate concern with Viet-Nam from understanding present-day events which in many ways are shaped by events at Dien Bien Phu in the spring of 1954.