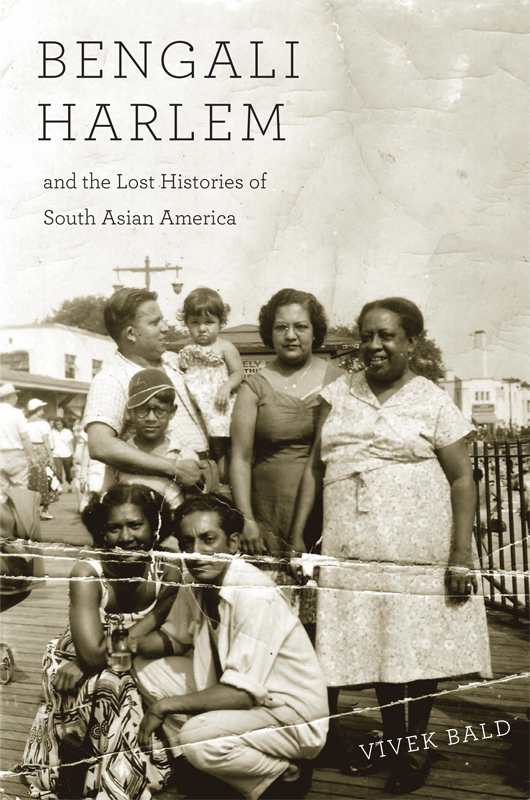

Vivek Bald - Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America

Here you can read online Vivek Bald - Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: History / Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Vivek Bald: author's other books

Who wrote Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America

Bengali Harlem

and the

Lost Histories

of

South Asian America

Vivek Bald

Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London England

2013

Copyright 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Jacket art courtesy Habib Ullah, Jr.

and the jacket designer is Graciela Galup.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Bald, Vivek.

Bengali Harlem and the lost histories of South Asian America / Vivek Bald.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-06666-3

1. South Asian AmericansHistory20th century. 2. South Asian AmericansCultural assimilation. 3. MuslimsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Working classUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. Haidar, Dada Amir. 6. United StatesRace relationsHistory20th century. 7. Harlem (New York, N.Y.)Race relationsHistory20th century. 8. United StatesEmigration and immigrationHistory20th century. 9. South AsiaEmigration and immigrationHistory20th century. I. Title.

E184.S69B35 2012

305.891'4073dc23

2012022231

For my daughter.

Contents

Lost in Migration

Lost Futures

A LTHOUGH MANY OF THE PEOPLE about whom I have written came from regions that are now part of the nations of Bangladesh and Pakistan, most of the period covered here pre-dates the creation of those nations. When I am writing about the pre-1947 period, I have chosen to refer to these individuals as Indian and their place of origin as India in order to maintain historical accuracy. I use the term South Asian when referring either to the post-1947 period or to a stretch of time that includes both the pre- and post-1947 periods. I use the term Bengali to refer to many of the individuals who appear in this book in order to specify their origins in the larger region of Bengal, both West (in present-day India) and East (in present-day Bangladesh). To many of these migrants, regional (Bengali) and sub-regional (e.g.: Sylheti) identity appears to have been more salient on a day-to-day basis than any national identification.

The research for this book entailed piecing together archival documentsship manifests; census enumerations; birth, death, and marriage certificatesin which British and U.S. officials transliterated South Asian names in multiple ways. The migrants whose lives and travels are recorded in these documents also likely used different English spellings of their names at different times. In the interest of clarity, I have standardized my spelling of specific individuals names within the text of the book. I have generally chosen the spelling that appears most frequently in the archives or the name that the individual appears to have settled on in his own daily life in New Orleans, Harlem, or elsewhere. These spellings often take forms that might be considered unorthodox by contemporary South Asian readers (e.g., Ally, Fozlay, Surker, Raymond, Box). When I refer to specific archival documents in the footnotes, I use the spellings that appear in those original documents.

I named this project Bengali Harlem early on in its development, when it focused primarily on a set of interconnected families of Bengali ex-seamen who had settled and intermarried in Harlem. At that time, the title was literal, referring to a particular set of people in a particular place. Over several years of research, as I followed an expanding trail of archival documents, the history I was piecing together grew far beyond Harlem and it grew to include many other people who were not Bengalifrom the Kashmiri seaman and activist Dada Amir Haider Khan to Creole, African American, and Puerto Rican women. Over time, the name has become metaphorical rather than literal, standing for a particular set of encounters and possibilities tied to South Asian life making and place making in U.S. neighborhoods of color.

Each and every identity is extended through a relationship with the Other.

douard Glissant, Poetics of Relation

Lost in Migration

I N M ARCH OF 1945, two men from India led testimony before the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization of the U.S. Congress.

Mubarek Ali Khan and J. J. Singh sought to change this status quo, and as they stood before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, the two Indian lobbyists could not have seemed more different. Khan was a graying middle-aged man who wore spectacles, plain suits, and a cap that marked his Muslim faith. At six feet, J. J. Singh towered over Khan. He was in his late forties, handsome, self-assured, and polished in both demeanor and appearance. He had short hair and was clean shaven, having dispensed with his turban and beard after settling in the United States, and he favored fine suits.

As different as the two bills were, Khan and Singh and their respective supporters had come to lean on similar arguments when they went before Congress. Both mens camps bolstered their cases for repeal of the naturalization laws by stressing the accomplishments of leading Indian Americans of the day, and each presented lists and biographies of these scientists, engineers, and scholars. Such individuals, they argued, were wronged by the current laws; they were prevented from becoming American citizens even though they had contributed their considerable knowledge and expertise to the United States. Khan also stressed the injustice suffered by large-scale Indian farmers, like those in Arizona, who could not own the land they had made productive. Singh spoke of the Indian businessmen who could not do meaningful business in the United States because they were restricted to short-term tourist visas. Both sides stressed the participation of Indian forces and Indian men in the war effort and touted the benefits of expanded U.S. trade with an India that would likely gain its independence at the wars end.

The majority of Indians who were living in the United States in 1945 and who were being prevented from becoming U.S. citizens were, in fact, not scientists, not businessmen, not engineers, scholars, or even large-scale agriculturalists. They were farm laborers and industrial and service workers. But in the 1945 hearing, this was mentioned only sporadically and often obliquely. Even Mubarek Ali Khan, who represented this group, was cautious in how he described the three thousand. J. J. Singh made a few references to the farm and factory workers, but always in the negative: that is, he assured the committee that because his bill required that most of the one hundred naturalizations per year be filled by Indians from India (rather than by those already living in the United States) his legislation would not result in a flood of Indian workers becoming U.S. citizens. Acknowledging that some congressional committee members were still worried about the so-called laboring classes, Singh went so far as to assure them that with the industrialization schemes that are afoot in India, I do not anticipate that [any workers] would care to leave India to come to the United States. As the hearings progressed, no one seemed willing to speak boldly for the silent majority of Indians in the United States, for a shadow population of migrants, spread across the country, who had dropped out of status as the immigration laws changed around them. No one, that is, except a Bengali from New York City named Ibrahim Choudry.

Choudry was a former director of an Indian merchant sailors club in Manhattan and seaman turned community activist, secretary of the India Association for American Citizenship. Although allied with Mubarek Ali Khan, he was willingand likely felt boundto be more forceful than Khan in his advocacy. In the midst of the March 1945 hearings before the Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, a letter that Choudry had written was introduced into testimony. There is no indication that it was read aloud, which likely means that it was simply handed by Khan to the appropriate clerk to be added to the typed record after the conclusion of the hearing. Shuffled into archival obscurity, Choudrys letter spoke up unequivocally for a population that other witnesses were less forthright in acknowledging. I do not speak here for the few, Choudry wrote:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America»

Look at similar books to Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Bengali Harlem and the Lost Histories of South Asian America and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.