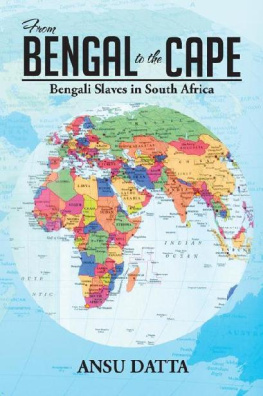

FROM BENGAL

TO THE CAPE

Bengali Slaves in South Africa

from 17 th to 19 th Century

ANSU DATTA

Copyright 2013 by ANSU DATTA.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012924354

ISBN: Hardcover 978-1-4797-7326-8

Softcover 978-1-4797-7325-1

Ebook 978-1-4797-7327-5

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

Xlibris Corporation

1-800-618-969

www.Xlibris.com.au

502429

Contents

Tables

Ansu Datta, sociologist and Africanist of a high order, had begun this research on Bengali slaves, especially women, bought and brought to South Africa, some years ago in Cape Town. Come to know of it from him, whom I had met after decades in connection with a volume I edited to which he contributed, I realized its importance in slave as well as population studies and suggested that he wrote a book on it. To compare notes, I referred him to a current Bengali novel built around the female slave traffic of about the time of his interest on the Bengal and Orissa coast. At my instance he had a talk too with the author regarding the latters sources. A long African sojourn and familiarity with the South African human geography were also conducive to him. The first draft was ready before long. There was an opportunity to try it out with a social sciences research group in Kolkata, and the response was most encouraging giving him every reason to put the final touches to his work and publish it. I even requested him to write a Bengali version of it so that the story could be available to the common Bengali reader. He assured me that he would do that after revising his English version. The revision did take a little time, for besides his text he had to spruce up the appendices. He might have done more, as was his wont, but his body didnt allow him. He fell ill with his manuscript on desk and passed away without seeing it in print. Our mourning for this gentle and perfect scholar, a rare human being, knew no bounds.

We are grateful to Xlibris for publishing it online and, thus, for its generosity in letting us remember him. I am writing these words as a former colleague at Jadavpur University, Kolkata where Ansu Datta had begun his teaching career.

Amiya Dev

Retired Professor of Comparative Literature

Jadavpur University, Kolkata

PS.

The above preface needs a small addition. It is likely that discrepancies, omissions or mistakes have occurred in the process of things being put together by someone who is not the author. For that I, his wife, take full responsibility. Secondly, a couple of documents listed in the contents of the manuscript had to be left out since their sources were not located in the authors many papers.

Finally, the contents of the book have been slightly rearranged. The author had felt that the documents listed were too important to be appended separately. But since these documents were not yet woven into the main text by the author, the only way to include them is as appendices. The readers may like to keep this in mind.

Large number of women and men were taken as slaves from Bengal to the Cape of Good Hope by the Dutch East Indies Company from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century. Yet very few of their descendants are aware of their Bengali roots. Professor Datta has left behind extensive notes on sources he had unearthed, along with information on other archives, which could be explored and exploited. It was his opinion that further useful work might be undertaken in this area. This book would have served its purpose if future scholars pick up the trail of the new direction charted by this author into a new aspect of slave trade and slavery in South Africa that deserves research and acknowledgement

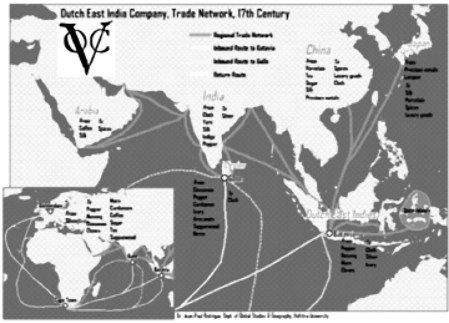

The map of the seventeenth century transoceanic trade routes of the Dutch East Indies Company, VOC, has been included in this book with the kind permission of Dr. Jean-Paul Rodrigue, Hofstra University, New York. For this I am really grateful to him.

Kusum Datta

Email:

Kolkata, India

Maps

1. The Cape of Good Hope in the 18 th century

javascript: Zoom(3032B12_to_323_plaat_Hottentots.jpg,%20en)

http://www.atlasofmutualheritage.nl/detail.aspx?page=dafb&lang=en&id=6413

2. Transoceanic VOC slave Trade Routes in the 17 th Century

Source: http://people.hofstra.edu/geotrans/eng/ch2en/conc2en/map_VOC_Tr

There have been several studies of African immigrants coming to India across the Arabian Sea. Some such immigrants were recruited and employed as soldiers by Hindu and Muslim rulers, as well as by Portuguese, French, and British colonial administrations. A few are known to have come as free merchants. Others were slaves brought to India under duress.

African immigrants were, and still are, known, generally, as Habshi. The word, derived from Abyssinia, modern-day Ethiopia, referred to the people from East Africa, especially from the Horn of Africa. Another common name for these people is Siddi or Sidi , the origin of which is debated. According to Suniti Kumar Chatterji (reprint 2004: 66) and Richard Pankhurst (2000), the term is a corruption of the Arabic word Saidi (my lord in English). How this word was later used in India to connote former slaves remains a socio-linguistic puzzle.

Pockets of Siddi settlements have been found in western India: Gujarat, Karnataka, and the Hyderabad region of Andhra Pradesh. According to one estimate, the Siddis in India currently number about 30,000 (Van Kessel, 2006: 461). Interestingly, Siddi (alternatively, Zanzibari) communities have also been found in Kwazulu-Natal, more precisely, Durban (Kaarsholm, 2008: 9-10).

In Indian historical records, we find various references to African slaves. In the first half of the thirteenth century, Queen Razias clandestine romance with an African slave led to tragic results. In the East, the offspring of African slaves ruled Bengal for a short period. Habshi rule in Bengal is generally traced to the reign of Ruknuddin Shah in the second half of the fifteenth century. Habshi power reached its peak during the last two decades of the fifteenth century when there were four successive Habshi sultans in Bengal. (Subramanyam, 1990: 118-19). Later, on the west coast of India, Habshi power emerged as a force to be reckoned with when the Siddis established themselves at a fort situated at a coastal village in Raigad, Maharashtra, locally known as Murud-Janjira. This is said to be the only fort along Indias western coast that remained free in the face of Maratha, Dutch and English East India Company. In actual fact, however, Siddis acted as feudatories of various political authorities on the Indian mainland, including the Mughals, but are said to have made a living mainly through piracy and coastal shipping.

Few Indians are aware of the forced migration in the opposite direction, i.e. export of Indian slaves to Africa. We find a mention of slave women from India exported to Sokotra Island in the Arabian Sea in Periplus of the Erythrean Sea (cited in Chananas Bengali translation 1995, pp. 143-44). There may have been other such cases. Unfortunately, there is little information about forced migration of Bengali (and other Indian) slaves to Africa, more precisely to the Cape Province in South Africa. It is known now that this process started in the seventeenth century and continued for more than two hundred years. Slaves were procured principally from three regions: Bengal, the Coromandel Coast, and Malabar.