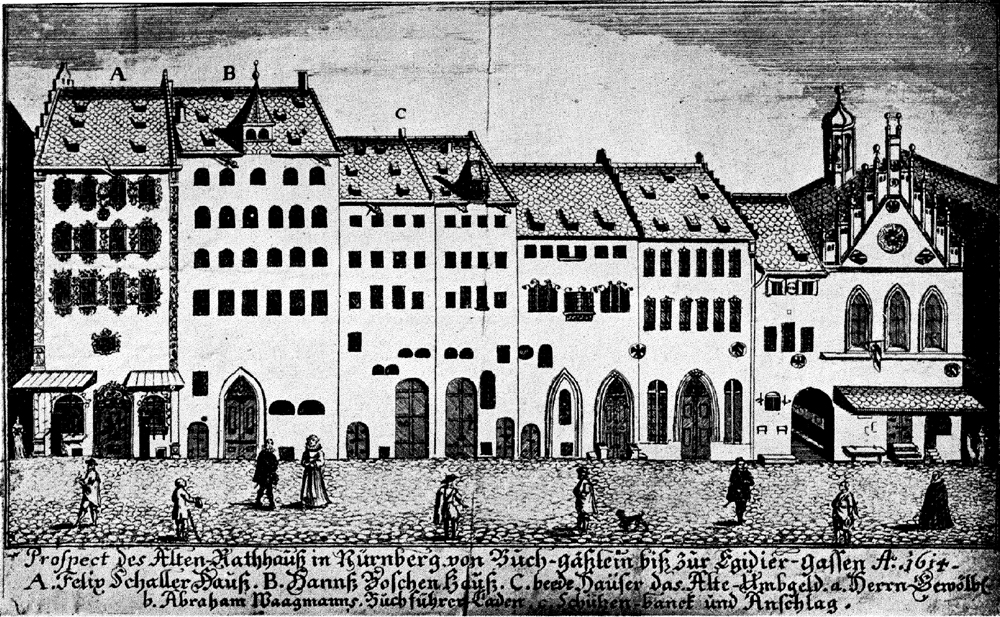

THE OLD TOWN HALL (RATHAUS) OF NUREMBERG

First published in 1928 by D. Appleton and Company

First Skyhorse Publishing edition, 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

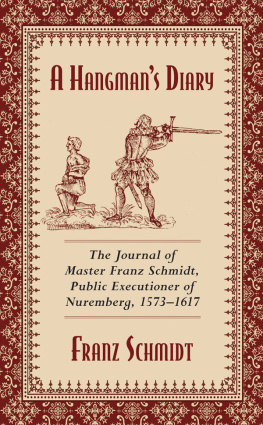

Cover design by Jane Sheppard

Cover photo The Execution of Hans Frschel by Master Franz Schmit, State Archives of Nuremberg

Print ISBN: 978-1-62914-480-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-62914-976-9

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE IN GERMANY IN THE MIDDLE AGES

by

C. C ALVERT

A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF CRIMINAL PROCEDURE IN GERMANY IN THE MIDDLE AGES

I. THE JAIL

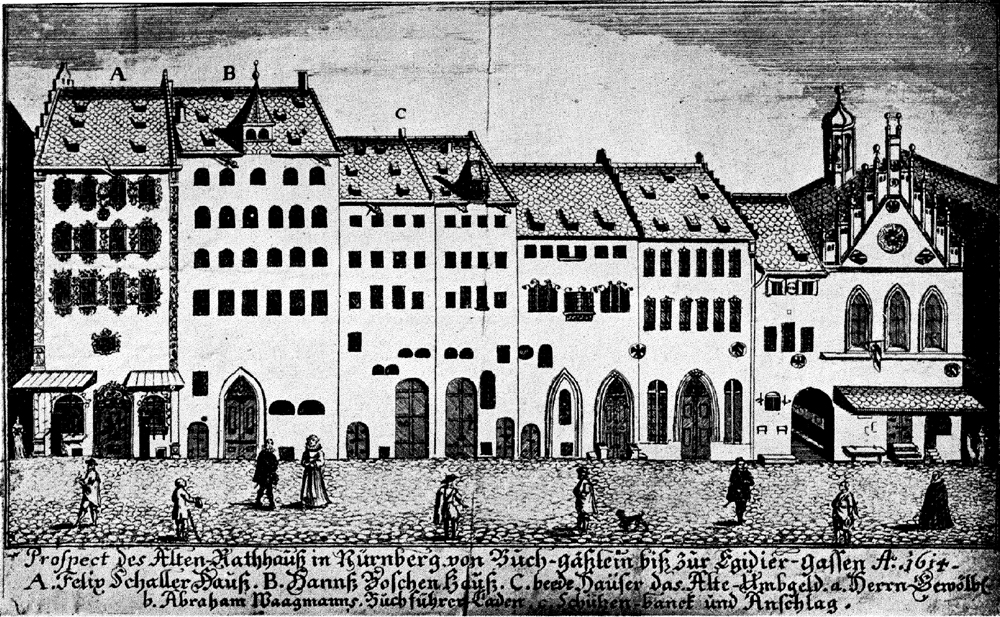

B ETWEEN 161622 the Nuremberg Rathaus was, to a large extent, enlarged or rebuilt, and further important additions were made during the second half of the nineteenth century; but the dungeons that honeycombed the foundations of the ancient structure have survived almost unaltered. A few cells retain some of their original fittings; it is therefore possible to form an accurate idea of the way in which lawbreakers were housed inside the Loch , when this was the principal jail of the City and Ban of Nuremberg.

Here, during those centuries, thousands of sinners and, unfortunately, not a few innocent people, spent weeks, months, or even years, in gloomy, underground cells, the horrors of which were aggravated by dampness, vermin, foul air, and defective sanitation. So bad were the conditions that prisoners released after any considerable term of confinement were found to be broken in health and often mentally enfeebled. Feuchtwangers Jew Sss gives a detailed, and not overdrawn, description of the effect that similar treatment had on a vigorous man in the prime of life.

The harsh fashion in which law-givers punished crime was, however, regarded with apathy by the public, who apparently considered imprisonment, whether wrongly or rightly inflicted, as one of the chances of fortune, or one of the many crosses laid on mankind by Heaven; a misfortune that might befall anyone, and which must, therefore, be borne patiently. Guests at the sumptuous banquets and entertainments given in the splendid Hall of the Rathaus were not troubled by compassion for the poor wretches lingering, often enough under sentence of death, in the dark cells only a few yards below.

Bad as was the Nuremberg jail, it long compared favourably with most contemporary prisons, either in Germany or elsewhere. Those of the neighbouring towns, Bornheim, Frankfurt, Mainz, and Landau, were assuredly no better; but the Nuremberg Government appears to have lagged behind in this respect, for a report on the Loch , published in 1799, states that in no other prison of the time were conditions so wretched. Everything was out of date; the cells still dark, damp, insanitary, infested with vermin; cleaned, at most, twice a month; and during the winter insufficiently warmed by braziers of burning charcoal, the fumes of which half suffocated the inmates. Medical attendance and spiritual consolation were almost entirely lacking, even for those who were in urgent need of them. Prisoners, many of them heavily ironed round the waist and at the feet, were confined for years, often together with their innocent children. Visitors and all means of passing away the time were still forbidden, as in the worst medival times. And yet, centuries before, the Karolina Code had expressly laid down that imprisonment should serve merely to secure the person, and not as a means of torture.

The Loch consists of a maze of passages, lighted, if at all, by narrow, barred windows. In these passages are sixty wooden doors, iron-lined, some of them bearing numbers. On one is the picture of a crowing cock, coloured fiery red; from which it is supposed that incendiaries were imprisoned there. On another door is painted a black cat, possibly because the cell was used to confine those under suspicion of magic or of witchcraft.

The masonry is of rough stone, and the cells measure, on the average, between nine and ten feet in length, about eight in breadth, and ten feet or so to the top of the vaulted roof. Originally the walls were bare, but later they were lined with heavy planks, which, as they did not follow the curve of the roof, considerably diminished the air space. Along the wall facing the entrance, at the height of approximately two feet from the floor, is a wooden shelf or bunk about a yard wide. A bench, also of wood, occupies one side of the apartment. In addition, the cells were formerly provided with a large, wooden, sanitary bucket, fitted with a lid that served as a table.

In the passage leading to the Torture Chamber are three larger apartments, the condemned cells. To these, after receiving sentence of death, prisoners were transferred and watched day and night to prevent suicide or attempts to escape. In one of these cells, besides the usual shelf, bench, and bucket, is a table on which the felons last meal was laid.

Another apartment contains the Stocks, an instrument freely employed, not only for the correction of ordinary rogues, but also to extract information from prisoners of war, unless such captives happened to be of good standing, and therefore valuable for the purposes of ransom or of exchange. The sanitary arrangements provided with this machine show that some of those who were locked in it suffered for days on end. It was customary to put such patients on short rations.

A narrow passage, formerly kept locked when not in use, leads to the surprisingly small and narrow Torture Chamber. In it we see a windlass and a wooden frame, furnished with a roller. Over this ran a rope to which the prisoner was fastened and then hoisted aloft with wooden, or stone, weights hanging to his feet. On the wall is a board bearing the sinister words: Male patratis sunt atra theatra parata . Formerly there were two torture chambers; but one was suppressed to provide an extra room for the Head Jailer.

The prison contained a repairing shop, by means of which, among other things, the torture instruments were kept in good order. There was also a bathroom, but this was so little used that its very existence seems to have been forgotten for a time. The few who benefited by it were those suffering from wounds received under torture, as well as prisoners who had contracted skin diseases and other complaints by reason of the damp and filth of the cells. These were so unhealthy that several entries record special grants of clothing to captives whose garments had rotted on them during confinement.