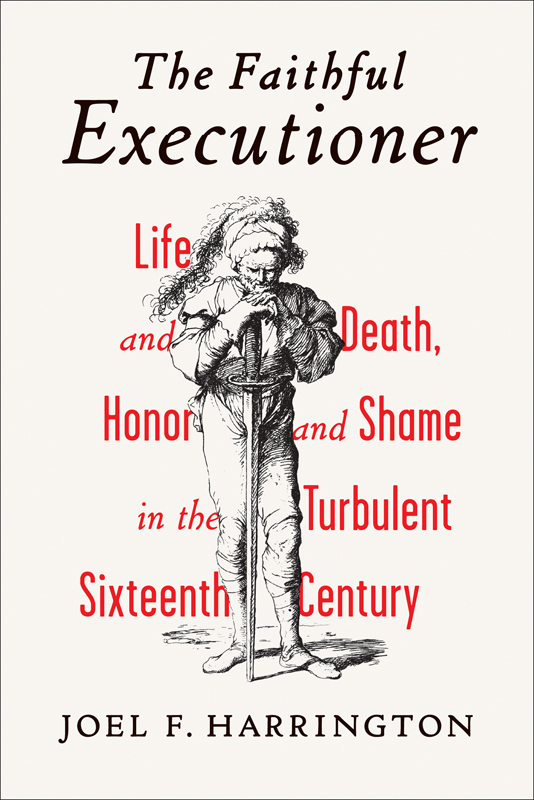

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my father, John E. Harrington, Jr.

Contents

Preface

Every useful person is respectable.

Julius Krautz, executioner of Berlin (1889)

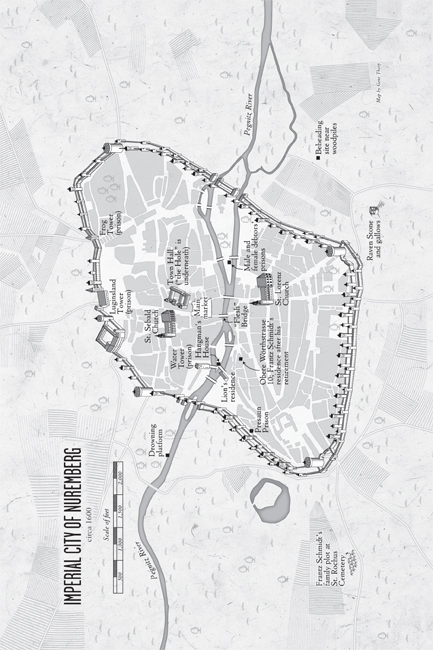

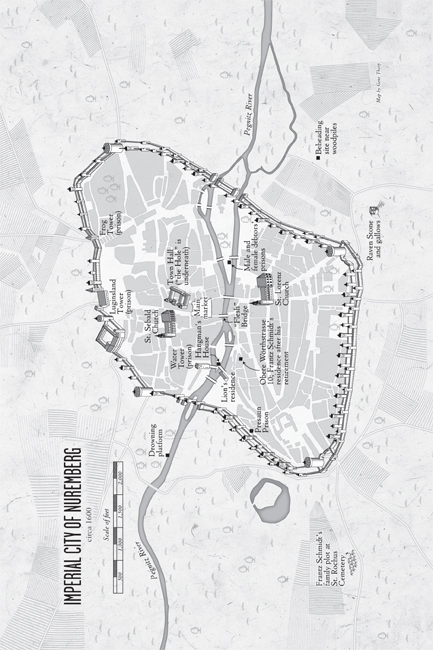

The sun has barely cleared the horizon when a crowd begins to form on the chilly Thursday morning of November 13, 1617. Yet another public execution awaits the free city of Nuremberg, renowned throughout Europe as a bastion of law and order, and spectators from all ranks of society are eager to secure a good viewing spot before the main event gets under way. Vendors have already set up makeshift stands to hawk Nuremberger sausages, fermented cabbage, and salted herrings, lining the entire route of the death procession, from the town hall to the gallows just outside the city walls. Other adults and children roam the crowd, selling bottles of beer and wine. By midmorning the throng has grown to a few thousand spectators and the dozen or so town constables on duty, known as archers, are visibly uneasy at the prospect of maintaining order. Drunken young men jostle one another and grow restless, filling the air with their ribald ditties. Pungent wafts of vomit and urine mix with the fragrant smoke from grilling sausages and roasting chestnuts.

Rumors about the condemned prisoner, traditionally referred to as the poor sinner, circulate through the crowd at a dizzying pace. The basics are quickly conveyed: his name is Georg Karl Lambrecht, age thirty, formerly of the Franconian village of Mainberheim. Though he had trained and worked for many years as a miller, he most recently toiled in the more menial position of wine carrier. Everyone knows that he has been sentenced to death for counterfeiting prolific amounts of gold and silver coins with his brother and other nefarious figures, all of whom successfully got away. More intriguing to the anxious spectators, he is widely reputed to be skilled in magic, having divorced his first wife for adultery and whored around the countryside with an infamous sorceress known as the Iron Biter. On one recent occasion, according to several witnesses, Lambrecht threw a black hen in the air and cried, See, devil, you have here your morsel, now give me mine! upon which he cursed to death one of his many enemies. His late mother is also rumored to have been a witch and his father was long ago hanged as a thief, thereby validating the prison chaplains assessment that the apple did not fall far from the tree with this one.

Shortly before noon, the bells of nearby Saint Sebaldus begin to ring solemnly, joined in quick succession by Our Ladys Church on the main market, then Saint Lorenz on the other side of the Pegnitz River. Within a few minutes, the poor sinner is led out of a side door of the stately town hall, his ankles shackled and wrists bound tightly with sturdy rope. Johannes Hagendorn, one of the criminal courts two chaplains, later writes in his journal that at this moment Lambrecht turns to him and fervently asks for forgiveness from his many sins. He also makes one last futile plea to be dispatched with a sword stroke to the neck, a quicker and more honorable death than being burned alive, the prescribed punishment for counterfeiting. His request denied, Lambrecht is expertly shepherded to the adjoining market square by the citys longtime executioner, Frantz Schmidt. From there a slow procession of local dignitaries moves toward the site of execution, a mile away. The judge of the blood court, dressed in red and black patrician finery, leads the solemn cortege on horseback, followed on foot by the condemned man, two chaplains, and the executioner, better known to residents, like all men of his craft, by the honorific of Meister (Master) Frantz. Behind him walk darkly clad representatives from the Nuremberg city council, scions of the citys wealthy leading families, followed by the heads of several local craftsmens guilds, thus signaling a genuinely civic occasion. As he passes the spectators lining his way, the visibly weeping Lambrecht calls out blessings to those he recognizes, asking their pardon. Upon exiting the citys formidable walls through the southern Ladies Gate (Frauentor), the procession approaches its destination: a solitary raised platform popularly known as the Raven Stone, in reference to the birds that come to feast on the corpses left to rot after execution. The poor sinner climbs a few stone steps with the executioner and turns to address the crowd from the platform, unable to avoid a glance at the neighboring gallows. He makes one more public confession and a plea for divine forgiveness, then drops to his knees and recites the Lords Prayer, the chaplain murmuring words of consolation in his ear.

Upon the prayers conclusion, Meister Frantz sits Lambrecht down in the judgment chair and drapes a fine silk cord around his neck so that he might be discreetly strangled before being set on firea final act of mercy on the part of the executioner. He also binds the condemned tightly with a chain around his chest, then hangs a small sack of gunpowder from his neck and places wreaths covered in pitch between Lambrechts arms and legs, all designed to accelerate the bodys burning. The chaplain continues to pray with the poor sinner while Meister Frantz adds several bushels of straw around the chair, fixing them in place with small pegs. Just before the executioner tosses a torch at Lambrechts feet, his assistant surreptitiously tightens the cord around the condemned mans neck, presumably garroting him to death. Once the flames begin licking the chair, however, it is immediately clear that this effort has been botched, with the condemned man pathetically crying out Lord, into your hands I commend my spirit. As the fire burns on, there are a few more shrieks of Lord Jesus, take my spirit, then only the crackles of the flames are heard and the stench of burnt flesh fills the air. Later that day, Chaplain Hagendorn, now fully sympathetic, confides to his journal, based on the clear evidence of pious contrition at the end, I have no doubt whatsoever that he came through this terrible and pitiful death to eternal life and has become a child and heir of eternal life.

One outcast departs this life; another remains behind, sweeping up his victims charred bones and embers. Professional killers like Frantz Schmidt have long been feared, despised, and even pitied, but rarely considered as genuine individuals, capableor worthyof being known to posterity. But what is going through the mind of this sixty-three-year-old veteran executioner as he brushes clean the stone where the convicted mans last gasps of desperate piety so recently pierced the thickening smoke? Certainly not any doubts about Lambrechts guilt, which he himself helped establish during two lengthy interrogations of the accused, as well as the depositions of several witnessesnot to mention the counterfeiting tools and other incontrovertible evidence found in the condemneds residence. Is Meister Frantz perhaps reenvisioning and ruing the bungled strangulation that made such an embarrassing scene possible? Has his professional pride been wounded, his reputation besmirched? Or has he simply been hardened to insensitivity by nearly five decades in what everyone considered a singularly unsavory occupation?