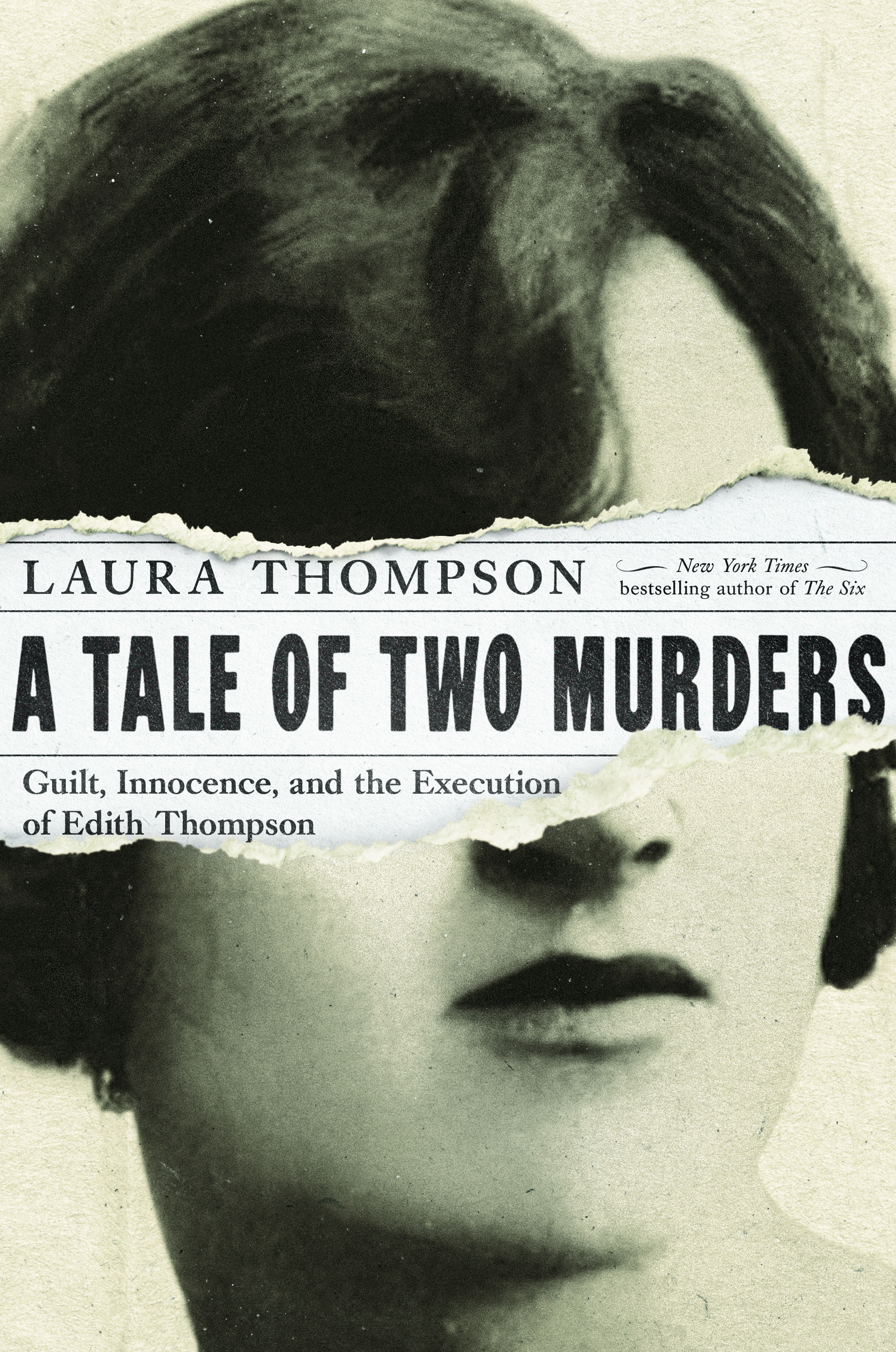

Laura Thompson - A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson

Here you can read online Laura Thompson - A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A TALE OF

TWO MURDERS

Guilt, Innocence, and

the Execution of Edith Thompson

LAURA THOMPSON

PEGASUS CRIME

NEW YORK LONDON

Whoever invented love ought to be shot.

As spoken in Love in a Cold Climate by Nancy Mitford

Please dont let me fall.

The last words of Mary Surratt, hanged in 1865

T HERE WAS A double hanging at Holloway jail on the morning of 3 February 1903. As Edith Graydon was skip-hop-skipping her way to school, travelling without foreknowledge through the neat, self-respecting, know-your-place streets of suburban east London, two women were waiting in their death cells to experience the last seconds of life. They had conspired together in their crimes, and they died side by side, in the same jolting moments of the morning. These were the first of the five hangings that would take place at Holloway, which had become an exclusively female prison in 1902.

Some murderers permit empathy, but Annie Walters and Amelia Sach do not: they were baby farmers, taking in unwanted children (of whom there were many) for an adoption fee, then disposing of them with chlorodyne. Such crimes were impossible to forgive. Despite the usual mitigating circumstance of poverty there was never any chance of a reprieve for Walters and Sach.

Anyway there was only muted opposition to the death penalty in 1903. Abolitionists had been making their case since the 1830s, but they did not really hit their stride until the 1920s, and even then the authorities remained adamantine. As Sir John Anderson, Permanent Under-Secretary of State in the Home Department, said in 1923 to the prison reformer, Margery Fry, those who opposed the death penalty were all too often sentimentalists.

So the public face of authority was obdurate, even as the stirrings of national queasiness were beginning to be felt (these came in waves, and were not felt by everybody). Throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, hangings had been the rampageous stuff of fatalistic folklore, part of the terrible theatre of daily life. From 1868 they took place in private, and perversely this made their reality less tenable. One knew where one was, at least, with the condemned who drank their nerves down on the ride from Newgate to Tyburn, and made bravura speeches to the open skies. The spectacle was appalling, but it was honest. Behind closed doors everything was contained within brick and stone, institutional buff and grey. It was measured and mechanistic, catalogued in paperwork by civil servants who blotted their words with passionless care. But it was still what it was. The form signed by the sheriff, the under sheriff, the prison governor, to the effect that they had witnessed the event how stately it looked, with its black flourishes and curlicues but the question remained: what had they witnessed? The inquest upon the executed person, conducted almost immediately and with such conscientiousness, with evidence and a jury, as if enclosing the event within the jaws of legal righteousness but still the words had to be written, in crabbed fountain pen, that the said person died from fractured dislocation of the cervical vertebrae.

The bureaucracy was absolute, however; it could not be faulted or gainsaid. Gentlemen, As directed in Standing Order no.459, I have the honour to submit the annexed Record of the execution of the above-named Prisoner: so ran the printed words on a form sent to the Home Office from the prison governor. When opened out, the form requested Particulars of the Execution. Rather like an examination paper in human biology, it asked for an Approximate statement of the character and amount of destruction to the soft and bony structures of the neck. A typical reply recorded Bruising of neck from rope. Fracture of odontoid process and right half of arch of Axis. Then came a request for The length of the drop as determined before the execution, and a subsequent request for The length of the drop, as measured after the execution, from the level of the floor of the scaffold to the heels of the suspended culprit. The answers to these two questions differed by a neatly inked two or three inches, nothing more.

There was also a Memorandum of Instructions for carrying out an Execution, drawn up in 1891 and amended three times, in reaction to events that did not quite go to plan. Again the attention to detail was irreproachable. The apparatus, meaning the drop, had to be tested a week before the hanging, first without any weight attached, then with a sandbag. As the gutta percha [rubber] round the noose end of the execution rope hardens in cold weather, the memorandum continued, for all the world as if advising on the best outcome for a recipe, care should be taken to have it warmed and manipulated immediately before the bag is tested. On the day before the hanging the apparatus was tested again, and the sandbag left in place overnight to take the stretch out of the rope. Then the execution shed, with its makeshift aspect and its array of basic tools, was locked. The key was kept by the prison governor.

As with the appointment of hangmen who knew their job, and killed with the intention to inflict a minimum of extraneous suffering men such as the Pierrepoints, whose family trade this was so every trouble was taken to make judicial execution a series of coolly predictable processes. Some of these could not help but be dramatic the piece of black cloth floating on the judges wig; the chaplain reciting I am the Resurrection and the life on the way to the scaffold but the rolling gravitas of ritual was, after all, what the supreme penalty required. And these rituals had God on their side, albeit a Low Church kind of God. What was going on was functional, formulaic, a regrettable necessity. Death for those found guilty of a capital crime was the due course of the law: a phrase so deliberately impersonal as to imply that the law had its own independent volition, and was not something created by mere people.

*

More accurately it was created by men. Gentlemen... Not until 1919 did a sole female legislator enter the House of Commons, and in 1922 two women were called to the English Bar I confess that at first I viewed the new step with alarm, the distinguished barrister Travers Humphreys (born 1867) would later write. He came round eventually, although he worried that women spoke too quietly in court, and wished that they would stay away from criminal law: There must be so much that is repulsive to a young woman in criminal practice.

Women, with their soft voices and soft bodies, were not equal with men at this time. They were so far from being equal that they could not even vote until 1918, and then only if they were aged thirty or more. Yet they were equal in this regard: they could be hanged.

At the very end of 1922 a time when the question of female execution was dominant in the news, and becoming almost dangerously emotive a document was drawn up by a senior Home Office civil servant, Sir Ernley Blackwell, and sent to Sir John Anderson. Its intention, as usual with this issue, was to codify and calm. It listed the women who had been convicted of murder in England and Wales since 1890, excluding infanticide (the specific crime of a woman killing her baby within a year of birth had recently ceased to be a capital offence: there was a dim understanding of the wretchedness that might lie behind it). Twenty-three names were typed on the document, together with a brief description of what they had done, and whether or not they had been executed for it.

Nine of the women had been hanged. Six of these had murdered other peoples children, a seventh was a sadistic mother. Condemnation was therefore an easy business. Of the remaining two, Mary Ann Ansell had poisoned her mentally incapacitated sister for 11 in life insurance unarguably cruel again while Emily Swann was executed, alongside her lover in another double hanging, for the murder of her husband.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson»

Look at similar books to A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Tale of Two Murders: Guilt, Innocence, and the Execution of Edith Thompson and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.