www.headofzeus.com

To my family

Contents

Law! What law can search into the remote abyss of Nature, what evidence can prove the unaccountable disaffections of wedlock? Can a jury sum up the endless aversions that are rooted in our souls, or can a bench give judgment upon antipathies?

G EORGE F ARQUHAR , The Beaux Stratagem , 1707

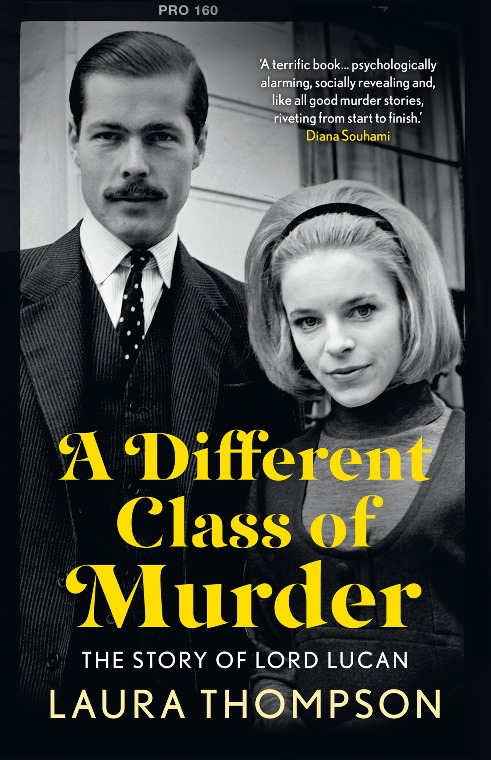

A Brief History of Murder, According to Social Class

Anything a Wimsey does is right and Heaven help the person who gets in his way.

D OROTHY L. S AYERS , Strong Poison , 1930

Do earls commit murder?

It is an incendiary question, in a country obsessed with class. Why shouldnt a peer of the realm be a murderer, the same as anybody else?

Why not indeed; yet murdering is something that they seldom do.

They have slaughtered to achieve advancement, of course, since historically that is how advancement was often achieved. An example: Richard Bingham, a soldier of fortune whose descendants became the Earls of Lucan, defended Ireland for Queen Elizabeth I and earned a knighthood for his savage efficiency. Peers have also killed by the careless exercise of inherited power. During the Irish potato famine of the 1840s, for instance, the 3rd Earl of Lucan cleared his Co. Mayo estate of poverty-stricken tenants, serving 6,000 processes for eviction, and eventually caused the workhouse gates to close in their death like faces.

But domestic murder: no.

In the last 500 years just eleven titled people have been tried for murder in England, two of them twice. A twelfth person, the 7th Earl of Lucan, was named guilty in 1975 by an inquest jury.

Of the eleven who faced trial, six were convicted of murder, and four of manslaughter. All were tried by their peers; meaning by other titled persons. This right continued until 1948, as did the tradition of the silken rope, with which aristocrats could be hanged more soothingly than with hemp. A further right was privilege of peerage, which could be pleaded by those found guilty of a first offence. It did not extend to murder, but it allowed a peer to walk free from a lesser charge.

When, therefore, the 7th Earl of Pembroke was convicted of manslaughter in 1678, he got away with it. The Lord High Steward warned him that his lordship would do well to take notice that no man could have the benefit of that statute but once, but Pembroke carried on exactly as before. In 1680 he was found guilty of murder, and received a royal pardon. His status as an earl clearly brought him an outrageous degree of favour. This did not extend to every aristocrat: three have been hanged for murder in the last 500 years. Yet Pembrokes treatment was far more typical. So too was the nature of his crimes. Both the deaths for which he was indicted were the product of boredom, booze and a belief that he could do whatever he liked at any given moment and too bad if somebody got hurt along the way. This, in murder and in much else besides, was the aristocratic way.

Pembrokes sense of entitlement defined him. He lived within his own world, according to his own crazy code of conduct. So too did the 4th Baron Mohun, a posh thug acquitted of murder in 1699 after a drunken duel in Leicester Square; and the 5th Baron Byron, great-uncle to the poet, who in 1765 put a sword through his cousins stomach and was let off with a fine. Later Byron shot his coachman. He did so in the manner of somebody taking a pop at a pheasant, just as Lord Pembroke, in 1680, had killed an officer of the watch who happened to be on a street where he was brandishing his blade.

It is unsurprising that the lower orders should have been so frequently the victims of aristocratic murder. In 1760, for instance, the 4th Earl Ferrers shot a man named John Johnson, a steward for his family estate. Ferrers was described as being of ungovernable temper, at times almost amounting to insanity, although this may, of course, have been simply a manifestation of extreme arrogance. It is very difficult to tell, in these cases, where arrogance ends and lunacy begins.

Ferrers was one of the few who did not get away with his crime. He was hanged at Tyburn, where he was denied the courtesy of the silk rope. This was the last occasion to date on which an aristocrat would be tried and convicted of murder in England. The excitable, damn ye sir passions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries had pretty much burned themselves out, although it was not until the last duel was fought, in 1852, that gentlemen would cease their particular kind of terrorizing street violence.

There had been innumerable deaths by duelling, very rarely resulting in any kind of prosecution. Of the handful that were charged, the last was the 7th Earl of Cardigan, who with his hated brother-in-law, the 3rd Earl of Lucan, would later preside over the hundred-plus deaths that occurred during the 1854 Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War. Thirteen years earlier, Cardigan had been tried for shooting a fellow officer in a duel. I have hit my man, he said. Yet in the House of Lords he was acquitted on a ludicrous technicality: his victim was wrongly named in the indictment, presumably in order to leave a loophole through which Cardigan could slide. In England, wrote The Times , there is one law for the rich and another for the poor.

That same year, 1841, the right to plead exemption from justice for a first offence was ended, but nobody really believed that privilege of peerage did not carry on regardless. In 1922, for instance, the public was convinced that Ronald True, a former RAF officer, had dodged the gallows because he was the illegitimate son of an unnamed peeress.

The thirty-one-year-old True had savagely murdered a prostitute in her London flat. His defence of insanity failed, and he was sentenced to death. However, when further medical evidence was presented to the Home Secretary, True was reprieved and sent to Broadmoor; and the public went berserk.

The sense of outrage was class-based. Even as Trues life was being saved, a pantry boy named Henry Jacoby, who had murdered his titled employer, was hanged despite a recommendation to mercy on grounds of youth. As it happened, Trues peeress mother was a creature of myth. He had simply been lucky. Yet the rage against his escape from justice, and the collective belief in the hidden powers of privilege, were intense.

The acquittal of Sir Jock Delves Broughton, tried for murder in Kenya in 1941, also tugged at the idea that posh people can get away with things. Broughton was accused of killing the Earl of Erroll, the lover of his far younger wife. These three belonged to what was known as the Happy Valley set, a collection of beyond-bored white settlers, who slept with each other in between drinking themselves silly: symbols of the deadly decadence of lives in which nothing is earned.

Although Broughtons acquittal had not been a foregone conclusion, the idea that this man would hang a baronet, an old Etonian never seemed quite real. As the verdict was about to be delivered, the foreman of the jury winked at the defendant and gave him a thumbs-up sign. Not all the Happy Valley set had rallied to his defence, although generally it closed ranks. And the stepdaughter of one of Broughtons friends, to whom he confessed murder, kept his secret for almost forty years. I can remember having it drilled into me, she later said, that a mans life hung on it and that every time I spoke to the police I mustnt say anything that might hurt him.

Next page