i

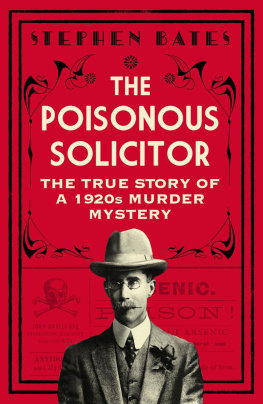

Immersive and compelling, The Poisonous Solicitor works at every level: as human drama, as an evocative slice of social and legal history, above all as a lucid and dispassionate presenting of the evidence about a century-old puzzle.

David Kynaston, bestselling author and historian

Stephen Bates puts us in the middle of an extraordinary trial for murder, when one life and many reputations were at stake. It was gripping then and fascinating now, with a shocking sting in the tale. You will read it in one sitting.

Marc Mulholland, author of The Murderer of Warren Street

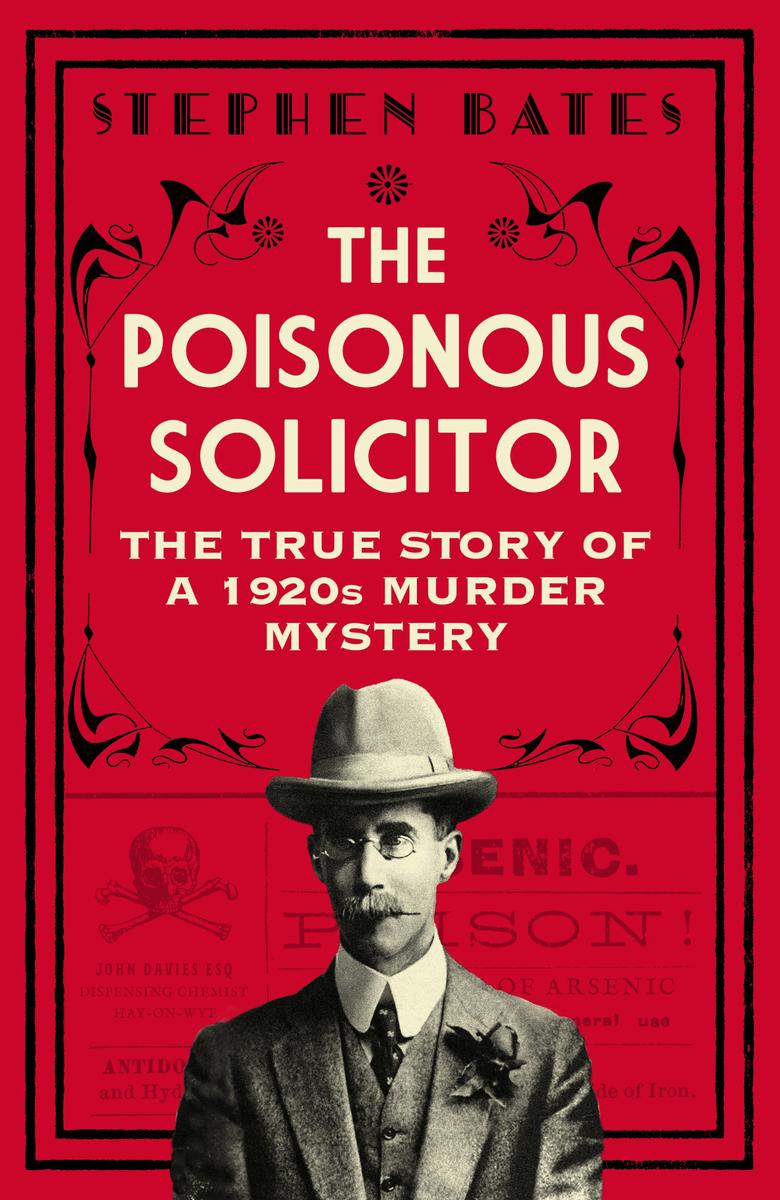

Marital disharmony, spare arsenic in the house, a premature death, the suspicions of nosey neighbours all leading to the judge putting on the Black Cap. Have you ever imagined you might find yourself sitting in judgement over a murder trial? Stephen Bates gripping narrative takes you right inside one of the classic court cases of the 20th century. His page-turner lays out all the evidence for you to examine, so you feel you are actually up there on the bench presiding over the dramatic trial of the only solicitor ever to be hanged in England. Guilty or innocent? You decide .

Robert Lacey, bestselling historian and biographer

Part Agatha Christie, part social history, Stephen Bates has stripped one of the classic 20th-century murders of a hundred years of conjecture and supposition, revealing a dark and troubling parable of inter-war rural Britain, a suffocating world of professional rivalries, rigid social codes and deadly small-town gossip where poisoned chocolates are delivered by first-class post. Finding nuance and ambiguity in what has often been viewed as a black-and-white case, The Poisonous Solicitor is a real-life golden age crime novel with a tragic heart and an unexpectedly poignant denouement.

Sean OConnor, author of Handsome Brute and The Fatal Passion of Alma Rattenbury

A careful and compelling reconstruction of one of the most infamous murder trials of the 20th century. Stephen Bates excels at contrasting the claustrophobia of small-town life with the grisly details which make the story still so notorious, a century on.

Kate Morgan, author of Murder: The Biography ii

v

For Alice vi

Stephen Bates read Modern History at New College, Oxford, before working as a journalist for the BBC, The Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail and the Guardian. He worked at the latter for 22 years as a political correspondent, European Affairs Editor in Brussels and religious and royal correspondent. A regular broadcaster, he has also written for a wide range of British and global newspapers and magazines. He is married with three adult children and lives in Kent. x

T he tale of Major Armstrong was a sensation on both sides of the Atlantic a century ago, in 1922. It was a life-or-death struggle played out in a country courtroom, a real-life tale of professional rivalries, gossip and poisoning in a small British market town, at a time when fictional murders in such settings were becoming bestsellers for authors such as Agatha Christie. Newspapers devoted tens of thousands of words to every twist and turn of the Armstrong story and they have returned to it periodically ever since. It has also been the subject of documentaries and at least one dramatic retelling, for the story, as contemporary writers such as Edgar Wallace knew, is extraordinarily dramatic and remains a real whodunit with many unanswered questions.

Since its notoriety in the 1920s however, there have been only two substantial retellings; one by the crime historian Robin Odell, called Exhumation of a Murder and published in 1975, which explicitly supported the police case that Armstrong was guilty: a born loser with his egotistical fantasies. The other, published twenty years later in 1995, was by Martin Beales, a solicitor who not only found himself working in the same office as the major, even occupying his desk and chair, but who also later moved into Armstrongs former home. He reached the opposite conclusion to Odell, in his book Dead Not Buried, that the major was framed, did not receive a fair trial and should not have been executed. Both books are formidably professionally researched and I have drawn on them, but xii their diametrically opposed views demonstrate that mystery remains. Twenty-five years on, although all the cast are now long dead, there are still documents and archives to explore, experts and relatives to listen to and previously overlooked stories to recount, shedding new light on a sensational story from the not-so distant past.

Stephen Bates,

Deal, August 2021

Ill build a stairway to Paradise,

With a new step every day.

L yrics by I ra G ershwin,

a hit for the P aul W hiteman B and in 1922

O n a bleak Tuesday morning in February 1921, a middle-aged woman named Katharine Armstrong died in her bedroom on the first floor of an imposing Edwardian villa overlooking the green fields and rolling hills of the isolated borderlands between Wales and England. Her last coherent words as she lay paralysed and terrified, five hours before her death, according to the nurse looking after her, were: I am not going to die, am I, because I have everything to live for my children and my husband.

It was a sad end for a woman who was only 48 years old, apparently happily married and with three school-aged children, but no more remarkable, seemingly, or tragic than the recent deaths of hundreds of thousands of young men in the trenches of the First World War which had ended a little over two years earlier, or thousands more men, women and children who had died in the influenza pandemic which had followed. It was a tragedy only for her children and her husband, who had just gone to work, cadging a lift with the local doctor who had been treating her for gastritis, inflammation of the kidneys and possible heart problems all manageable conditions for the previous eighteen months or so.

Within three days she was buried in the local churchyard at Cusop, the hamlet just outside Hay-on-Wye where the couple lived, and where her husband Herbert was a long-established and well-liked solicitor, magistrates clerk, a churchwarden and a pillar of the local Freemasons lodge: the very definition of respectability.

The best and truest wife has gone to the Great Beyond and I am left without a partner and without a friend, he allegedly wailed to an acquaintance. But despite an obituary in the local Brecon and Radnor Express under the headline A Popular Hay Lady, there were few mourners: Herbert and the Chicks, as it said on the card attached to the familys wreath; Dr Tom Hincks, the local GP and his wife; Mrs Griffiths and her son Trevor from the rival solicitors firm in the town and Emily Pearce, the Armstrongs housekeeper. Few other people in Hay paid much attention.

Yet, within fifteen months of such a sad domestic tragedy, Herbert Rowse Armstrong would be arrested, tried and hanged for her murder, the only solicitor ever to be executed in England, certainly in modern times. The domestic tragedy in a remote corner of the country became an international media sensation and a distraction from the worlds other news. The loving husband would become a villain of the age, one of the most notorious figures of the 1920s. A dapper, punctilious, little man with a waxed moustache who usually wore gilt-rimmed pince-nez spectacles, he would become more than a murderer at the centre of a case that the judge at his trial described in strangulated judicial syntax as so deeply interesting that I doubt whether any of us have in recollection a case so remarkable. He would, in fact, become an archetype: a member of the professional classes who had unaccountably turned bad and been caught out by a simple slip.