Royalty Inc.

(Said to be the Queens private motto)

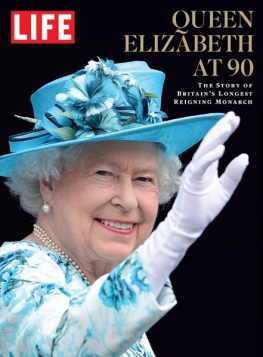

W hoever wrote the original words to the National Anthem, the signature tune of Britain, probably at some time in the first half of the eighteenth century, could not have known how apposite they would still be two and a half centuries later. Our noble Queen has certainly lived long longer than any previous monarch in the nations history and she has long reigned over us too, generally happily and graciously, though gloriously may be more a matter for debate. You have to be in your seventies now to remember a time when she was not the monarch. Indeed, if you were born on the day she became Queen you cant be far off reaching retirement and collecting your state pension.

The Queens longevity is a tribute to her robust health, but how is it that the institution she represents, based on some very quaint traditions and dated assumptions, tracing its origins back more than a thousand years, has not only managed to survive but to flourish well into the twenty-first century? There are very few enduring monarchies in the world in democratic countries: they are basically restricted to a fringe of western Europe, and the British monarchy is by far the best known of them. More than a governmental system, an ancient flummery or a tourist trap, it is, arguably, the most famous non-commercial brand in the world. Our small, sprightly, octogenarian Queen, after more than sixty-three years on the throne, is one of the most famous women anywhere on earth, as recognisable to someone in Tokyo or Tulsa, or even Timbuktu and Tuvalu, as in Tooting or Truro. Everything about her on the surface is familiar, from her dress sense pastel colours, off-the-face hats to her voice, reminiscent of a different era and class. We know she likes dogs and horses and Scotland, that in private she is a good mimic and sometimes sardonic, that she hates being late, that she is strongly religious and is very conscientious and stoic. What we dont know is what she thinks about almost anything: her opinions are unknown and unknowable, a blank. Her inscrutability is the secret of her success. If we really knew anything about her thoughts, the monarchy would rock: its apparent impartiality is its greatest strength, for almost any opinion held by the sovereign would divide the country, whereas having none publicly goes a long way towards uniting it.

For a journalist it is the greatest frustration: how do you report on someone you cannot talk to? With the possible exception of Kim Jong-un, the Supreme Leader of North Korea, the Queen is the only person on the planet who cannot be interviewed even Pope Francis regularly chats to the media these days. We can guess what she is like and speculate for all we are worth, the Queen even occasionally shows passive emotion, but ultimately the mask never slips. We may think we know what she is really like, but do we? As Lord Fellowes, her former private secretary, told a new member of staff: Just because she is friendly, it does not mean she is friends with you.

Everyone knows (or thinks they know) her family, too. The royal soap opera trundles on, less thrilling perhaps than twenty years ago, but still fulfilling all the requirements of an ongoing weekly saga: the matriarch with an ageing husband apt to speak his mind too freely and put his foot in it; the frustrated eldest son with the turbulent lovelorn backstory; the young married couple with babies; the dull and grasping younger children. Characters come and go, some die off, others arrive and plots emerge, then peter out, but the story continues. It is a seeming anachronism which remains incredibly popular much more so than most other institutions in Britain or abroad, shining bright in public affection, untarnished like politicians, or the church, the media, the bankers or big business. This is one company that has somehow pulled off the trick of seeming never to change, but yet it always manages to evolve, quietly, inconspicuously but firmly: as familiar in its way as a Coca-Cola bottle or a Marmite jar. A new label here, a new ingredient there, a plastic bottle instead of a glass one, a new taste sensation. We think iconic brands do not change, but they do and if they do it too drastically or obviously, they suffer. Equally, if they do not change, they decline and die. Royalty is a bit like that. It has been changing successfully for years, centuries even, without most people really noticing. It is not the same institution it was when the Queen came to the throne in 1952; in many ways it has changed out of all recognition and so it sails on. This book seeks to track the changes and explain how the monarchy has achieved its transformation. How has it pulled it off? And will it continue to do so?

The parameters are easy to discern, as are the changes to the lives of those she governs. Queen Elizabeth II is not the longest-reigning sovereign in history. Shell have to last nearly another twenty years to beat King Sobhuza of Swazilands eighty-two years and 254 days between 1899 and 1982, until 2024 to whizz past Louis XIV of France and 2019 to beat the Emperor Franz Josef of Austria and who knows when the reign of the King of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, who has . But in Britain the sixty-three years and 216 days that Queen Victoria was on the throne will be eclipsed on 9 September 2015. Remarkably, at the time of writing, Britain has had a female head of state for 127 of the past 180 years. The British Empire has long gone partly assembled in the reign of Queen Victoria, it has been completely dismantled in the time of her great-great-granddaughter but she still remains sovereign of sixteen realms, from the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize, Antigua and Barbuda to St Christopher and Nevis, and about 130 million people are her subjects. Any proposed change in the monarchs constitutional position in the UK requires their agreement as independent states too. The Commonwealth has replaced the empire: fifty-three independent nations, encompassing a third of the worlds population, and the Queen is at its head. Even countries that were never ruled by the British, such as Mozambique, have joined and those thirty-one member states that are now republics still acknowledge her: they recognise the organisation as a useful and beneficial international association, bound together by a colonial history, mainly a common language and shared traditions. In the words of the then Australian prime minister Julia Gillard in 2011, in a country that has strong republican traditions, not least in Gillards party: the Queen remains a vital, constitutional part of Australian democracy. If the Queen sometimes seems the most enthusiastic member of the Commonwealth, she also gives it something that other transnational bodies lack. She distinguishes us from the United States, as one Canadian commentator said to me during a royal trip. Shes something they dont have.