For my mother, Anne Valerie Marr, sometimes mistaken for

Contents

PART ONE

PART TWO

PART THREE

PART FOUR

PART FIVE

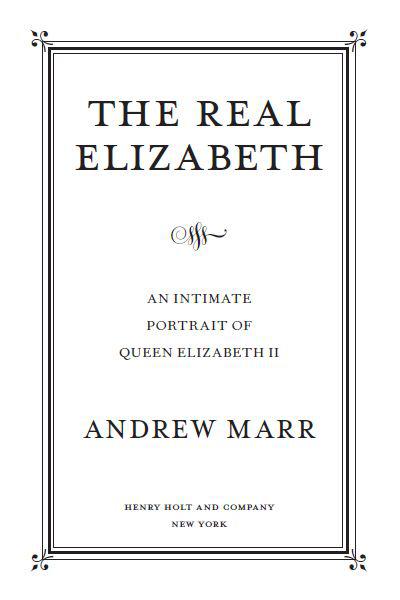

Preface to the U.S. Edition

Why should Americans be interested in Queen Elizabeth II, monarch of the United Kingdom and fifteen other countries, from Canada and Australia to tiny Tuvalu? It is a good question. She is a kind of anti-celebrity, a woman happiest in scarf, old coat and rubber boots, out with her dogs or horses. Though enormously wealthy, she eats frugally, keeping her breakfast cereals in plastic boxes and switching off unnecessary lights as she passes through rooms. She has a wonderful smile when she chooses to use it, but otherwise her face falls naturally into a rubbery solemnity she herself has likened to Miss Piggy. Her formal power is very small, and almost entirely irrelevant to the lives of those who are not her subjects.

Her son Charleswho as he approaches his own old age looks increasingly like his Hanoverian ancestor George III, the King who lost the American coloniesis hardly a celebrity either. The last time Americans became fixated by his story was when he separated from his far more media-friendly wife Diana, who was later killed in a Paris road accident. Now, with Kate Middleton, the middle-class woman whose wedding to Prince William, the Queens grandson, was watched by a third of the worlds television audience, the House of Windsor may have a new star. But the Queen herself has never played to the cameras and lives a life about as out of step as its possible to be from the glossy, brash, fast-moving world of comtemporary culture.

This is exactly why she ought to fascinate anyone interested in American politics and history, as well as those simply curious about modern royalty. And since the Queen has no equivalent in the United States, her story presents a series of striking contrasts. The first, most obvious one is that she has been head of state for so very long. In 2012 she celebrates her Diamond Jubilee, marking the sixtieth anniversary of her accession to the British throne. Before our eyes, she has grown from the willowy, dark-haired young mother of the 1950s into the shrewd great-grandmother of today. Now, at eighty-five, she is the second-longest-reigning monarch in British history. Only her great predecessor Queen Victoria spent more time in Londons palaces. That means she has known, personally and sometimes quite well, every U.S. President since Harry Truman. Of all of them, she was probably closest to Ronald Reagan, although she and her ninety-year-old husband Prince Philip have struck up an unlikely-seeming cordiality with the Obamas. Whatever one thinks about her, the Queen and her long reign have provided the British people with a sense of continuity unlike any that can be found in a democratic republic.

For many of us, she is the only British monarch we have ever known. Her father, King George VI, died on February 6, 1952, less than seven years after the end of World War II. She inherited the throne in the same year Stalin died, Truman announced the hydrogen bomb and the Rosenbergs were executed; it was also the year the first edition of Playboy magazine appeared, Elvis Presley graduated from high school, and Kinsey electrified America with his report on female sexuality. During her reign, the Queen saw the final transition of the British Empire into a Commonwealth of fifty-four countriesan organization that comprises about a third of the worlds population yet is unknown to most Americans. She met the leaders of the post-Stalin Soviet Union, such as Khrushchev and Bulganin, and became the first British monarch to visit Russia since the killing of Tsar Nicholas and his family in 1917. She had a ringside seat from which to witness the disastrous British and French invasion of Nassers Egypt and the terrifying Cuban missile crisis. She remembers historic figures such as Charles de Gaulle and Haile Selassie. She has seen her country go from being overwhelmingly white to a multiracial world island with hundreds of new communities. She has reigned through the Korean and Vietnam wars, the worst stages of the Cold War, Perestroika, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Iraq and Afghan wars and the rise of China.

Across all those years, the Queen has devoted a good part of every day except Christmas to a close reading of the private paperwork of the British state, secret intelligence reports and paperwork about humdrum appointments alike. She has a wicked enthusiasm for mimicry and a phenomenal memory, so although she is deadlock-discreet, her recall of the events and players of modern times is probably unparalleled. This vast store of knowledge has proved beneficial, particularly because of her role as a private counselor and informal therapist to a long procession of prime ministers. The early ones, including Winston Churchill, rather bullied her; the later ones have mostly been in awe of her. In hard times she has been able to talk them through earlier, parallel crises and so provide invaluable perspective.

Monarchy can allow for the longer view. Americans, like the British, live their politics on a four-year electoral cycle, but the biggest issues we face play out over much longer time spans than that. Energy security, climate change, mass migration, long-term government debt and species extinction are hard for political leaders to focus on, given that they tend to think only a year or two ahead. By their nature, Royals think in generations, and its useful to have someone in a position of influence consider the long-term implications of a policy or a program.

Another contrast worth noting is Elizabeth IIs own view of her role. Though we live in a secular and materialistic age, the Queen believes, quite literally, that she has a vocationthat her function is a religious calling she must answer every day of her life. When she was anointed with a secret recipe of oils at her Coronation in 1953, a tradition going back to ancient Jewish custom, she accepted a life-long position that can more easily be compared to religious service than to modern politics. This, perhaps more than anything, explains her remarkable humility. She is, in fact, a shy person whose nerves can still get a little shaky before she makes a speech, which is quite remarkable given that she spends most of her life meeting strangers and making speeches. No wonder her outspoken husband has said that no one in their right mind would choose to do her job.

The Real Elizabeth is, I hope, very different from most books about the British royalty that are published in the United States. There is an insatiable and entirely understandable appetite for gossip and scandal, and it must be said that even in a world so full of both, the House of Windsor has done its bit for splashy sensation. The essential outbreaks of royal mayhem are described and analyzed here too: without understanding the disastrous reign of Edward VIII or the breakdown of the marriage of Charles and Diana, we cannot possibly understand the Queens reign. Further, I have spoken to many of those who know and work with the Queen, and I have tried to provide a rounded portrait of her as a woman as well as a monarch. My sources have included many of the politicians, officials and courtiersas well as members of the Queens close familywho never speak about the Queen and her role in public, and only rarely to outsiders, even in private.

My ultimate purpose here is to show how monarchy has actually worked, through the various political periods and crises of modern times, and to explain and make the case for a system of government that will strike most Americans as little short of bizarre. In other words, I have taken the Queen seriously, on her own terms. She is, after all, singular. No other ruler of a major country has lasted so long in modern times, or had to cope with such a mixture of international and family crises. It is a pretty safe prediction that there will never be anyone like her again. She is, in her own way, a major world figure whose story is both stranger and more complex than most people know.

Next page