Contents

Contents

Guide

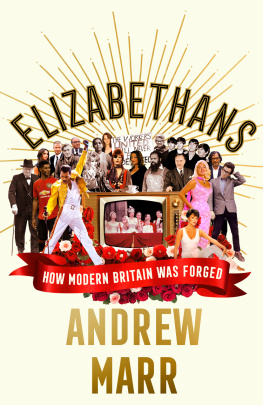

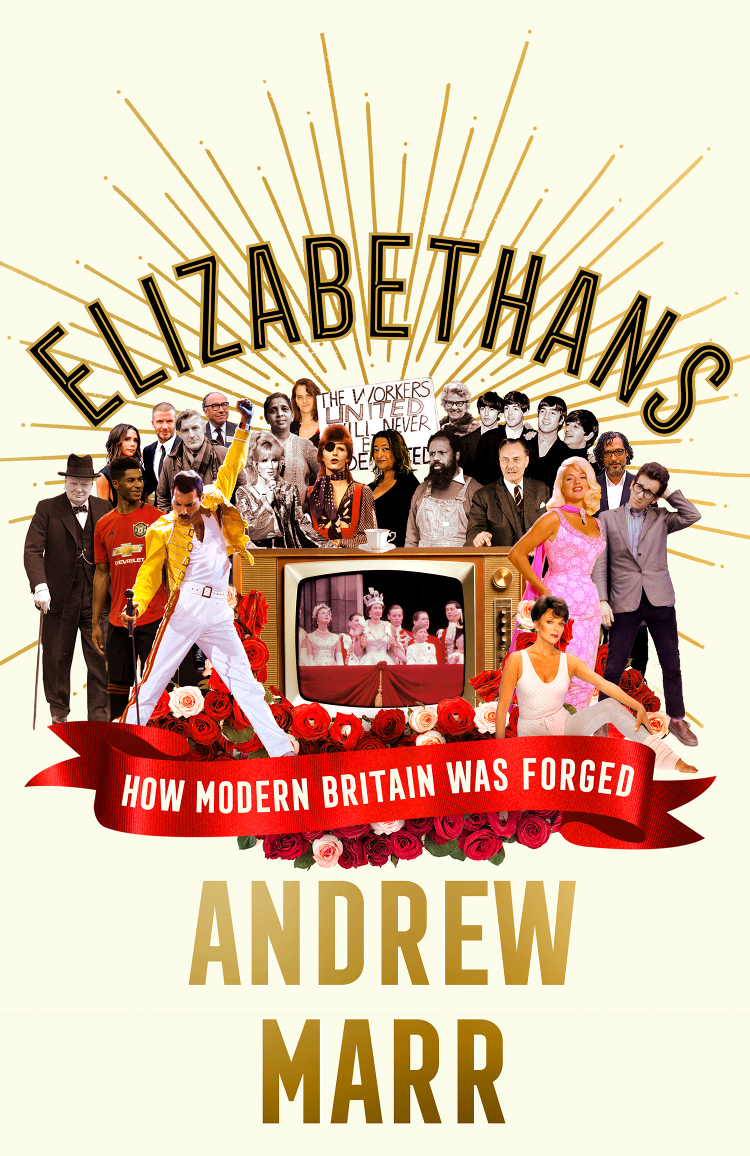

ELIZABETHANS

How Modern Britain was Forged

Andrew Marr

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2020

Copyright Andrew Marr 2020

Extract from Jan Morriss Conundrum (Faber & Faber Ltd) used with the kind permission of the publisher

Extract from Robin Morgans Monster, Monster: Poems (Random House and Vintage Press, 1971). All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of the author

Cover design: Jo Thomson

Andrew Marr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008298401

Ebook Edition October 2020 ISBN: 9780008298425

Version: 2020-09-03

In memory of William Donald Marr, 19302020,

a wonderful father and a fine Elizabethan.

O n the evening of 5 April 2020, speaking at Windsor Castle and attended by a single BBC cameraman hidden behind protective clothing, Queen Elizabeth II gave the fourth televised address of her reign outside her annual Christmas messages. She was talking to the British about coronavirus, as deaths soared and most of her subjects chafed indoors under tight government restrictions. Her subject was patriotism. As she was speaking, her Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, was being taken to St Thomass Hospital in London, where he would be placed briefly in intensive care, as his coronavirus symptoms worsened.

The Queen was too subtle to compare the coronavirus crisis directly with wartime conditions. Indeed, she emphasized the difference: This time we join with all nations across the globe in a common endeavour using the great advances of science and our instinctive compassion to heal. However, the separation of family made necessary by social distancing and the general lockdown in homes made her, she said, think back to the broadcast she had made during the Second World War to the evacuee children.

The Queen repeated the governments key messages about staying at home and supporting the NHS she had not spent her life as head of state for nothing before making her central patriotic appeal.

In the years to come everyone will be able to take pride in how they responded to this challenge. And those who come after us will say, the Britons of this generation were as strong as any; that the attributes of self-discipline, of quiet good-humoured resolve and of fellow feeling, still characterize this country. The pride in who we are is not part of our past. It defines our present and future.

This is without doubt how most British people would like to think of themselves. The Queen went on to mention specifically the then regular 8 p.m. Thursday applause for NHS and key workers, which would be remembered as an expression of our national spirit.

Our national spirit is quite close to being the subject of this book. Exceptionalism how different are we? is the staple question of all national history. Yet, in modern circumstances and particularly during a global pandemic, it may be the wrong question.

Most developed human societies are moving in roughly the same direction when it comes to their economies, attitudes to fairness and rights, and their failures, particularly over the environment. There are renegade countries and dissenting civilizations, such as Hungary, Russia and China far more so than when the end of history was vaingloriously proclaimed after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. But among liberal democracies todays Elizabethan Britain is broadly in the mainstream. After Brexit, it is still (much) more like other European cultures than unlike.

So let us turn to that Thursday applause, both origin and object. It should not be too much of a surprise that inspiration came not from a native Briton but from Annemarie Plas, a thirty-six-year-old Dutch software saleswoman and yoga teacher, who got the idea from friends in the Netherlands. Her message, sent by a variety of social media, read: Please join us on 26th March at 8pm for a big applause (from front doors, garden, balcony, windows, living rooms, etc) to show all the nurses, doctors, GPs, and carers our appreciation for their ongoing hard work and fight against the virus.

All over Britain, huge numbers of people heeded her call. Soon, among those standing on their doorsteps or in their houses to clap were many members of the Queens family, the Prime Minister and actors such as Daniel Craig. Television channels made a point of stopping normal programming to record it.

It was heartwarming and proper, and made most British people feel better. But it wasnt a specifically British thing. Locked-down individuals and families in virus-hit Lombardy, in southern Italy and in Spain had done similar things as, of course, had the Dutch.

Then there are the identities of those who were being applauded. As the New York Times reported three days after the Queens address, of the first eight doctors who died in Britain of coronavirus while treating it, all were immigrants here. Lists of those who had died began to appear in newspapers. One, in the Daily Telegraph, at around the time of the Queens address, included the following names: Abdul Mabud Chowdhury, a fifty-three-year-old Muslim consultant virologist working in Romford Essex, who had recently warned the government about the lack of personal protection equipment in hospitals; Edmond Adedeji, sixty-two, working in Swindon; Fayez Ayache, seventy-six, who had migrated from Syria, working in Ipswich; Alice Kit Tak Ong, a seventy-year-old nurse from Hong Kong, working in the Royal Free Hospital in North London; Jitendra Rathod, fifty-eight, a heart surgeon working at the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff; Alfa Saadu, from Nigeria, still working at sixty-eight in the Whittington Hospital North London; and Adil El Tayar, a sixty-three-year-old Sudanese doctor working in Middlesex. The New York Times listed the countries from which the first dead had come as being India, Nigeria, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Sudan.

Again, anyone familiar with modern Britain would be unsurprised by that list. The British National Health Service has long relied on doctors and nurses who have migrated here from poorer countries. European medical staff, at the beginning of the epidemic, may well have gone back to their own health services to help; and sadly it is not a surprise that immigrant doctors were on the front line doing some of the most dangerous jobs when it struck. But had something similar happened in the early years of the Queens reign, then the surnames of the dead doctors would have been more likely to read Wilkins, Smith, Walker, McDonald, Davies, Jones.