AN ARISTOCRACY OF CRITICS

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2020 by Stephen Bates.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by IDS Infotech, Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935082

ISBN 978-0-300-11189-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

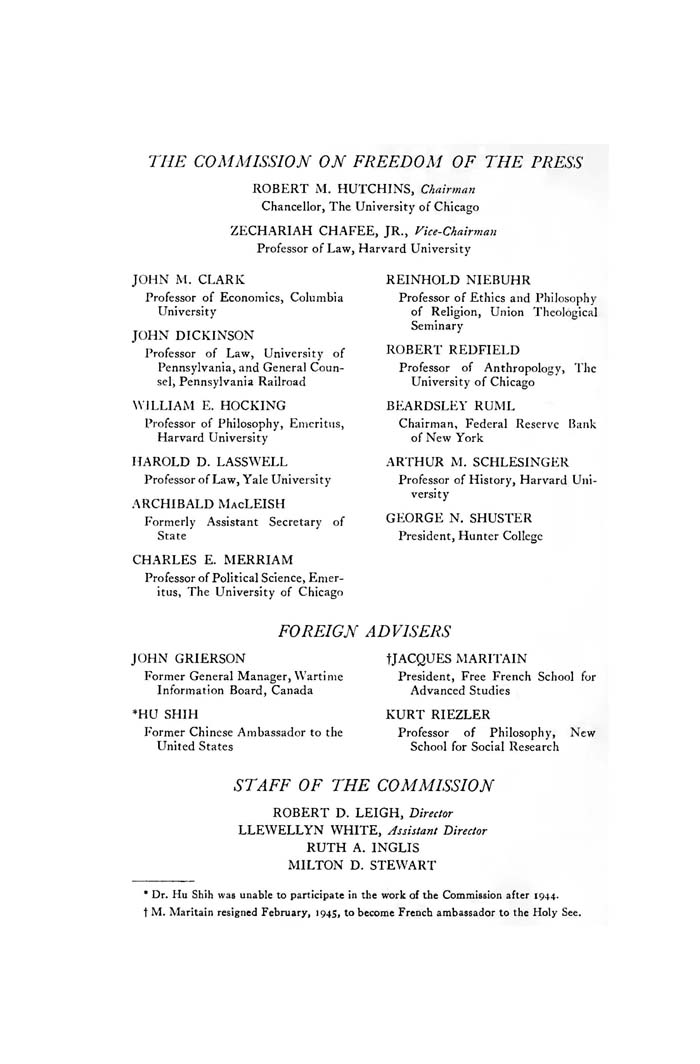

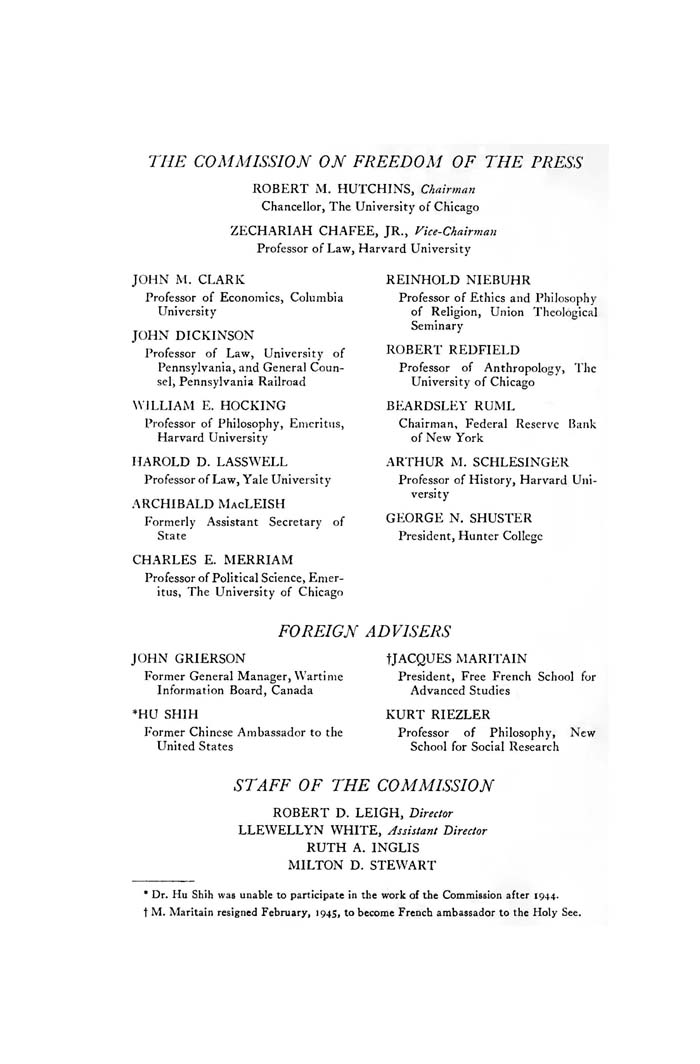

Frontispiece: A Free and Responsible Press (1947). (From A Free and Responsible Press, by the Commission on Freedom of the Press, edited by Robert D. Leigh; 1947 by The University of Chicago; reproduced by permission)

Excerpts from Time Inc. staff documents 1944, 1945, 1946, 1947, 1948, 1949, 1952, 1964, 1968 by TI Gotham, Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted/translated and published with permission of TI Gotham Inc. Reproduction in any manner in any language in whole or in part without written permission is prohibited.

Some material in this book appeared in different form in the following:

Stephen Bates, Is This the Best Philosophy Can Do? Henry R. Luce and A Free and Responsible Press,Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 95, no. 3 (2018): 811834. Copyright 2017, Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communications. DOI: 10.1177/1077699017719873.

Stephen Bates, Prejudice and the Press Critics: Colonel Robert McCormicks Assault on the Hutchins Commission, American Journalism 36, no. 3 (Fall 2019): 420446.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Clara and Charlotte

Contents

AN ARISTOCRACY OF CRITICS

Introduction

I N DECEMBER 1942 , Robert Maynard Hutchins met Henry R. Luce for lunch at the Drake Hotel in Chicago. Hutchins, the nations best-known educator, ran the University of Chicago. Luce, one of the nations best-known publishers, ran Time Inc. Arms-length friends since they first met as Yale undergraduates, both were cerebral, opinionated, and sharp-tongued, esteemed in some circles and abhorred in others. Out of their conversation that day would come the most extraordinary collaboration of American thinkers in the twentieth century, the Commission on Freedom of the Press. Hutchins and a dozen fellow intellectuals would investigate newsroom bias, distrust of the media, foreign and domestic propaganda, corporate domination of political discourse, a fragmenting and polarized electorate, hate speech, and demagoguery, as well as what we now call echo chambers, trolls, deplatforming, and post-truth politics. These problems afflicted the United States of the 1940s. Many of them afflict the United States of today.

Luce came up with the idea. Corporations, he told Hutchins, underwrite scientific research at the University of Chicago. What about a corporate-funded philosophical study? If Time Inc. provided the money, would the university convene a committee of intellectuals to rethink freedom of the press? No, said Hutchins. It couldnt be done. In subsequent encounters, Luce kept pushing. After a year, Hutchins agreed. The idea was audacious, but so were the men: Luce, proclaimer of the American Century, and Hutchins, anointer of the Great Books of the Western World.

Hutchins coined the grandiose name, the Commission on Freedom of the Press, and the two men recruited a group of intellectual superstars, including Reinhold Niebuhr, the foremost American theologian; Zechariah Chafee Jr., the preeminent First Amendment scholar; Archibald MacLeish, librarian of Congress and Pulitzer Prizewinning poet; Charles E. Merriam, a pioneering political scientist; William Ernest Hocking, an acclaimed philosopher; and Harold D. Lasswell, a propaganda expert and chief architect of the emerging field of media studies. Hutchins called them some very eminent characters. All were men, and most were professors, but not the sort who devoted their careers to the microscopic study of Byzantine mosaics, as Hutchins derided the gullies of academic specialization. These were foxes rather than hedgehogs, in Isaiah Berlins terms, men who articulated and defended big ideas: Hutchins versus John Dewey on the ideals of education, MacLeish versus James T. Farrell on the duties of the artist, Merriam versus Friedrich Hayek on the role of the state, Niebuhr versus Merriam on the arc of history. These men left the college cloisters and worked for President Franklin D. Roosevelt, testified before Congress, charted the course of policy, and opined on matters cosmic and quotidian. They were leading figures in what Luce called the aristocracy of critics.

Hutchins, one of the nations most sought-after speakers, appeared twice on the cover of Luces Time. His pronouncements made headlines. He championed isolationism before Pearl Harbor and world government after Hiroshima. He spoke out against greed in business, relativism in philosophy, electives in college, and physical exercise in leisure time. As his profile rose, many well-regarded Americans came to believe that the president of the University of Chicago ought to be president of the United States. Hutchins thought so too.

To Hutchins and others, it seemed an opportune moment to appraise the American media. Tabloids were pandering to the basest instincts of the crowd. Head-to-head newspaper competition was diminishing, and publishers were snapping up radio licenses. More and more media outlets were in the hands of fewer and fewer corporations. The corporations grew, but the political debate within the media didnt. Major news organizations ranged from Colonel Robert R. McCormicks Chicago Tribune, with its far-right fulminations against FDR, to Luces Time, with its center-right fulminations against FDR. President Roosevelt publicly complained about the press and privately plotted revenge through federal agencies, while his allies in Congress launched harassing investigations and threatened draconian regulations. Polls detected public animosity, too. In 1936, when researchers asked Americans which institutions were abusing their power, the press ranked number one, ahead even of bankers.

Newspaper publishers, for their part, acclaimed the press as an indispensable pillar of American self-government, a bulwark of democracy enshrined in the First Amendment not for its own sake but for the sake of the citizenry. (Whenever publishers gather together, said Harold Lasswell, expect to hear about bulwarks.) The Commission on Freedom of the Press, chaired by Hutchins, proposed to take the platitudes seriously. If the press is servant of the people, hows the service? After 17 meetings, 58 witnesses, 225 staff interviews, 176 documents, $215,000, and a lot of false starts and dead ends, the commission published its conclusions in a report, A Free and Responsible Press, in 1947.

From the name, one might expect the Commission on Freedom of the Press to have championed a new birth of freedom. Instead it called for a new burden of responsibility, backed by a tacit threat of punishment. American journalists, according to

Next page