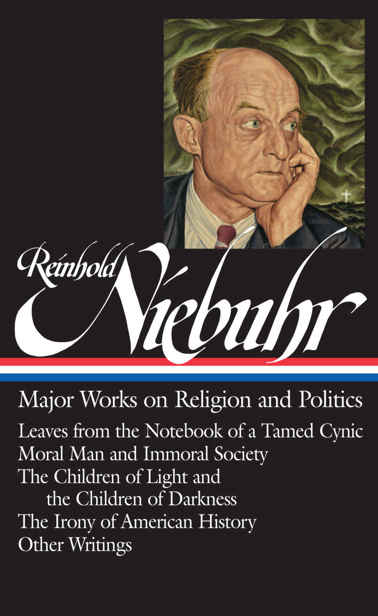

REINHOLD NIEBUHR

MAJOR WORKS ON RELIGION

AND POLITICS

Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic

Moral Man and Immoral Society

The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness

The Irony of American History

Other Writings

Elisabeth Sifton, editor

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2015 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced commercially

by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without

the permission of the publisher.

Visit our website at www.loa.org

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about The Library of America, and to sign up to receive our occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors, and our popular Story of the Week e-mails.

Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic copyright 1929, renewed 1957 by Reinhold Niebuhr. Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics copyright 1932 by Charles Scribners Sons, renewed 1960 by Reinhold Niebuhr. The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: A Vindication of Democracy and a Critique of its Traditional Defense copyright 1944 by Charles Scribners Sons, renewed 1972 by Ursula M. Niebuhr. The Irony of American History copyright 1952 by Charles Scribners Sons, renewed 1980 by Ursula M. Niebuhr. All works reprinted by arrangement with The Estate of Reinhold Niebuhr. All rights reserved. See Note on the Texts on page for sources and acknowledgements.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014946648

Print 9781598533750

eISBN 9781598534054

Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics

is kept in print with a gift from

PETER H. & JOAN M. KASKELL

in memory of his parents

JOSEPH KASKELL

(18911989)

a friend of Reinhold Niebuhr,

who translated into German Niebuhrs

The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness

and made possible its postwar publication in Germany

and

LILO KASKELL

(19011970)

photographer of Reinhold Niebuhr.

Contents

LEAVES FROM THE NOTEBOOK OF A TAMED CYNIC

TO

my friends

and former coworkers

in

Bethel Evangelical Church

Detroit, Michigan

Preface and Apology

M OST OF the reflections recorded in these pages were prompted by experiences of a local Christian pastorate. Some are derived from wider contacts with the churches and colleges of the country. For the sake of giving a better clue to the meaning of a few of them, it may be necessary to say that they have as their background a pastorate in an industrial community in which the natural growth of the city made the expansion of a small church into a congregation of considerable size, in a period of thirteen years, inevitable. By the time these lines reach the reader the author will have exchanged his pastoral activities for academic pursuits.

It must be confessed in all candor that some of the notes, particularly the later ones, were written after it seemed fairly certain that they would reach the eye of the public in some form or other. It was therefore psychologically difficult to maintain the type of honesty which characterizes the self-revelations of a private diary. The reader must consequently be warned (though such a warning may be superfluous) to discount the unconscious insincerities which no amount of self-discipline can eliminate from words which are meant for the public.

The notes which have been chosen for publication have been picked to illustrate the typical problems of a modern minister in an industrial and urban community and what seem to be more or less typical reactions of a young minister to such problems. Nothing new or startling was attempted in the pastorate out of which these reflections grew. If there is any justification for their publication, it must lie in the light they may throw upon the problems of the modern church and ministry rather than upon any possible solutions of these problems.

The book is published with an uneasy conscience, the author half hoping that the publishers would make short shrift of his indiscretions by throttling the book. Some of the notes are really too inane to deserve inclusion in any published work, and they can be justified only as a background for those notes which deal critically with the problems of the modern ministry. The latter are unfortunately, in many instances, too impertinent to be in good taste, and I lacked the grace to rob them of their impertinence without destroying whatever critical value they might possess. I can only emphasize in extenuation of the spirit which prompted them, what is confessed in some of the criticisms, namely, that the author is not unconscious of what the critical reader will himself divine, a tendency to be most critical of that in other men to which he is most tempted himself.

The modern ministry is in no easy position; for it is committed to the espousal of ideals (professionally, at that) which are in direct conflict with the dominant interests and prejudices of contemporary civilization. This conflict is nowhere more apparent than in America, where neither ancient sanctities nor new social insights tend to qualify, as they do in Europe, the heedless economic forces of an industrial era.

Inevitably a compromise must be made, or is made, between the rigor of the ideal and the necessities of the day. That has always been the case, but the resulting compromises are more obvious to an astute observer in our own day than in other generations. We are a world-conscious generation, and we have the means at our disposal to see and to analyze the brutalities which characterize mens larger social relationships and to note the dehumanizing effects of a civilization which unites men mechanically and isolates them spiritually.

Our knowledge may ultimately be the means of our redemption, but for the moment it seems to rob us of self-respect and respect for one another. Every conscientious minister is easily tempted to a sense of futility because we live our lives microscopically while we are able to view the scene in which we labor telescopically. But the higher perspective has its advantages as well as its dangers. It saves us from too much self-deception. Men who are engaged in the espousal of ideals easily fall into sentimentality. From the outside and the disinterested perspective this sentimentality may seem like hypocrisy. If it is only sentimentality and self-deception, viewed at closer range, it may degenerate into real hypocrisy if no determined effort is made to reduce it to a minimum.

It is no easy task to deal realistically with the moral confusion of our day, either in the pulpit or the pew, and avoid the appearance, and possibly the actual peril, of cynicism. An age which obscures the essentially unethical nature of its dominant interests by an undue preoccupation with the application of Christian principles in limited areas, may, as a matter of fact, deserve and profit by ruthless satire. Yet the pedagogical merits of satire are dubious, and in any event its weapons will be foresworn by an inside critic for both selfish and social reasons. For reasons of self-defense he will be very gentle in dealing with limitations which his own life illustrates.