I FIRST HEARD ABOUT HENRY B. WHIPPLE WHEN I HAPPENED to be a few miles from his birthplace in Adams, New York, one early March day, cold even by northern New York standards. I had come up Interstate 81 to lecture at a community college in Watertown, the last city a driver sees before crossing the bridge over the Saint Lawrence River into Canada.

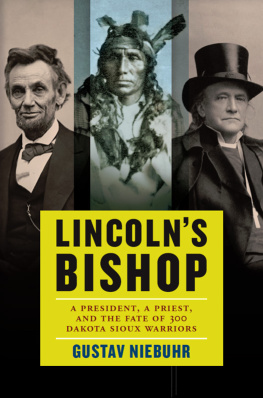

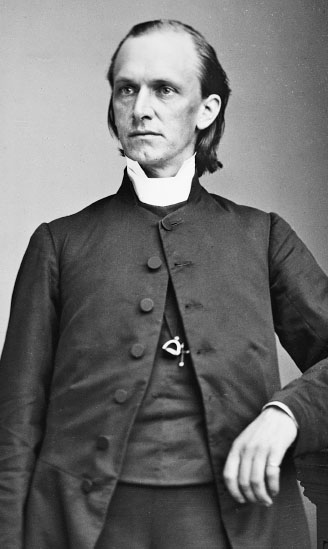

To orient me, my hosta newspaper editor deeply invested in his communityshared a handful of names of local, historic figures he admired. Whipple was near the top of his list. The name did not register with me, so he helpfully supplied an epitaph: He was the Episcopal bishop who went to see Lincoln to try to stop a mass hanging of the Sioux Indians. That sentence landed with an impact that made me want more information, and I sought it as soon as I got back to Syracuse University, where I teach. I pursued the bishop from there. I found that, yes, Whipple did go to see Lincoln about the Sioux (henceforth to be called by their own name, the Dakotas), but the visit took place in a much larger, more impressive context: years of Whipples advocacy, including several trips and letters to Washington in which the bishop demanded a sweeping reform of how the U.S. government treated Native Americans. Whipple acted as a one-man movement, seeking respect and protection for American Indians to replace the monstrous fraud and injustice to which he saw them subjected.

It took me little time to find in the story a contemporary resonance. I had recently had occasion to reread one of the most powerful Christian documents of my lifetime, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.s Letter from a Birmingham Jail. It seemed to speak to Whipples best work, as a dedicated social reformer laboring on behalf of abused people amidst a time of great violence.

Kings essay, written principally to white moderates during the Civil Rights campaign in 1963, focuses on the paradox of religious figures and institutions that claim moral authority yet do little with it, despite being figuratively sunk to their breastbones in the poisonous waters of injustice. Kings prose bore heartbreaking witness. On sweltering summer days and crisp autumn mornings I have looked at the Souths beautiful churches with their lofty spires pointing heavenward. I have beheld the impressive outlines of her massive religious-education buildings. Over and over I have found myself asking: What kind of people worship here? Who is their God?

Early Christians, he recalled, confronted head-on the Roman Empires social abuses. Their acts of dangerous defiance contrasted with the largely silent Southern church of his own time, one he said had a

Whipple does not bear comparison with King. Who does? But he possessed a motivation similar to the vision King commanded. He placed Christianity above race and ethnicityspecifically focusing on Native Americansat a time when few whites, clergy or otherwise, did likewise.

That an individual Christian might act as if the requirements of the faith trump racial and cultural divisions is a difficult task, but not an impossible one. Perhaps because something similar had happened within my own extended family, I felt all the more drawn to Whipple. In 1952, my uncle Lansing Hicks, a young Episcopal priest from North Carolina who had married my mothers middle sister, resigned in protest from his position as a professor of theology at a divinity school in Tennessee. It was the job he had always wanted. He had a toddler son, and his wife, my aunt Helen, was pregnant with their second child. But the schools trustees raised a serious moral obstacle when they declined to desegregate the school, which would have allowed African Americans to study there. Lansing, along with seven of his colleagues, rebuked the board, declaring its decision untenable in the light of Christian ethics. The trustees remained unmoved. My uncle gave up his dream job, resigning along with his seven colleagues.

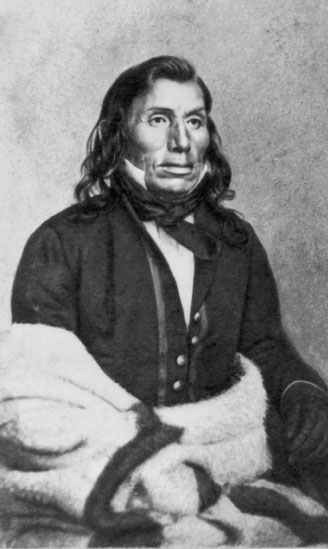

In the mid-nineteenth century, journalist John OSullivan coined the phrase manifest destiny, shorthand for white Americans territorial ambitions and the related belief the Indians would vanish before them. As a newly consecrated bishop, Whipple moved to Minnesota in 1859, a year after its political leaders had adopted the idea of manifest destiny on an official state seal, showing a white farmer at his plow watching an Indian ride into the setting sun. Whipple arrived a missionary, eager to preach to Indians and whites alike, but he did not subscribe to a vision of Native American dispossession. That made him a countercultural figure.

A month after Whipple took up residence in the state, he began lobbying on the Indians behalf, and when he finally reached President Lincoln, he did so at what a less determined individual would have recognized was the worst time possible. In September 1862 the Dakota War spread death and terror across Minnesota, its principle victims white civilians; the states leaders demanded Native Americans be exterminated. That did not stop Whipple. He recognized that moral authority, when kept sheathed like a sword in its scabbard, eventually loses its purpose.

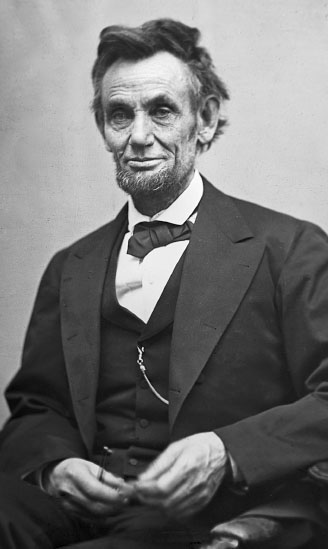

WHEN HE STEPPED ACROSS THE THRESHOLD INTO Abraham Lincolns White House in September 1862, Henry Whipple had come directly from the war that had thrown his state into upheaval. Minnesotas first Protestant Episcopal Church bishop, Whipple estimated that eight hundred civilians had lost their lives, and many bodies still lay unburied on the prairies and creek banks where they had fallen. He had come to tell Lincoln how this catastrophe had occurredand, more important, how a future such disaster could be avoided.

By coincidence (or, as some might have it, the hand of providence), the bishop chose an extraordinary moment to approach Lincoln. The very week he went to see the president, more than seventy-five thousand Union troops marched west through Maryland to confront General Robert E. Lees Army of Northern Virginia, which had crossed the Potomac River in a daring invasion of the North. That Wednesday, the Army of the Potomac, commanded by General George McClellan (whom Whipple counted as a friend), fought Lee outside the village of Sharpsburg, at Antietam Creek. By sunset, more than twenty-two thousand men were dead, wounded, or missing, making that September 17 the bloodiest single day in American history. Neither side emerged clearly victorious, but McClellan had possession of the battlefield, a tactical win that would stifle talk in Europe about its governments recognizing the South as an independent nation. In the office in which he would meet Whipple, Lincoln had quietly drafted an executive order to free nearly four million men, women, and children held as slaves. He kept the document in a desk drawer, awaiting a sign from God that the moment had come to make it public. He would recognize Antietam as providing that sign.