Contents

Guide

Page List

For Lily and her generation, that they

may grow up in a country that values honesty

and freedom of expression

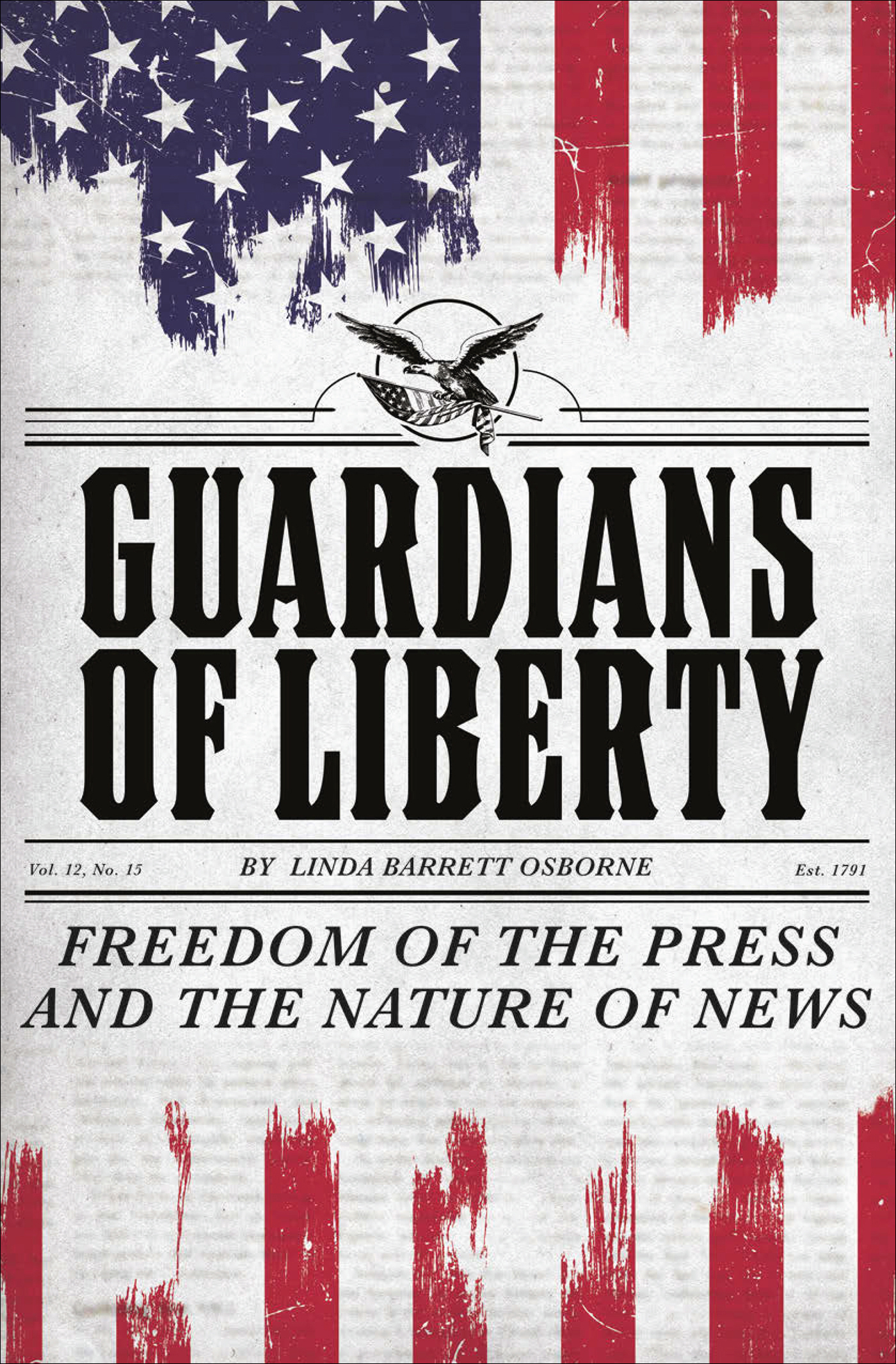

Title page: American eagle and coat of arms. Woodblock. 1882.

Incidental line illustrations: Introduction: Gavel. Chapter 1: Inkwell and goose feather quill pen. Chapter 2: Early printing press. Chapter 3: Linotype typesetting machine. Chapter 4: Vintage radios. Chapter 5: Vintage television. Chapter 6: Notepad, pen and press pass. Chapter 7: Space satellite. Chapter 8: Mobile phone. Microphone. Chapter 9: Megaphone.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for and may be obtained from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-1-4197-3689-6

eISBN 978-1-68335-627-1

Text copyright 2020 Linda Barrett Osborne

Edited by Howard W. Reeves

Book design by Erich Lazar

Published in 2020 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Abrams Books for Young Readers are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

The Eighteenth Century: Partisan Press and Revolution

CHAPTER 2

Congress Does Make a Law

CHAPTER 3

News, Politics, and War in the Nineteenth Century

CHAPTER 4

Twentieth-Century Presidents, War, and the News Media

CHAPTER 5

Civil Rights, Vietnam, and the News Media

CHAPTER 6

Freedom for the Student Press

CHAPTER 7

National Security, 9/11, and Press Censorship

CHAPTER 8

Fake News, Real Lies, and the Press

CHAPTER 9

Keeping the Press Safe for Democracy

INTRODUCTION

Congress shall make no law... abridging the freedom... of the press, states the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. This amendment was one of tencalled the Bill of Rightsadded to the Constitution in 1791. For more than 220 years, it has guaranteed that the federal government cannot stop news media from publishing news, ideas, and opinions, even those that disagree with the actions and policies of presidents and lawmakers. Protecting any Americans printed news or opinion is exactly what the First Amendment was meant to do.

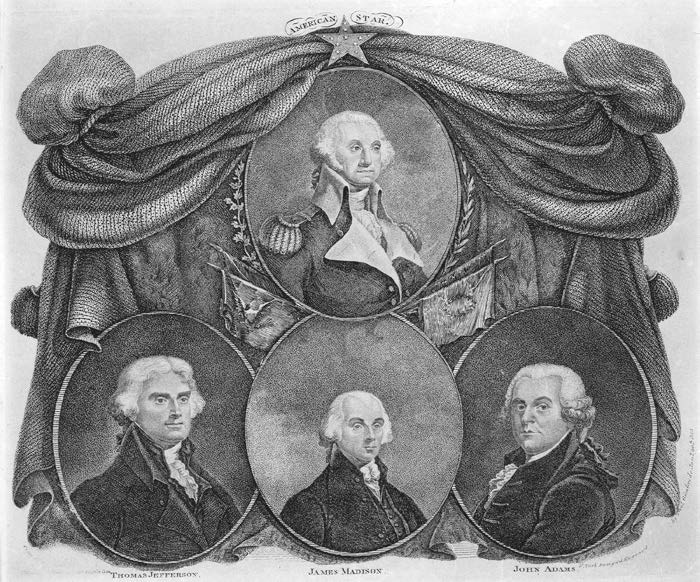

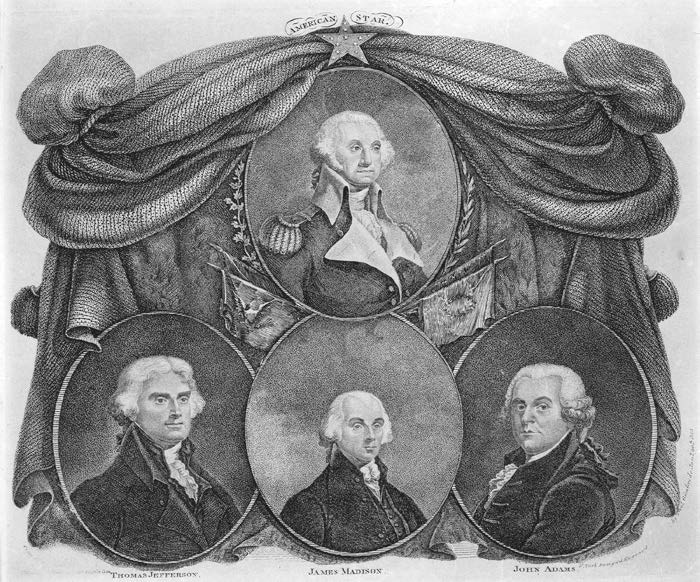

We live in a time when media technologythe way news is deliveredhas changed dramatically. It is also a time when much of the news has been attacked by a president as being fake and unbelievable. Knowing the story of why freedom of the press was important to the Founding Fathersmen like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madisonand how it has stayed a strong principle in American law and culture can help us understand its value today.

This engraving shows portraits of four of the Founding Fathers. George Washington is at the top, and the others are (left to right) Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Adams. The founders of the United States believed that freedom of the press was an essential right.

There were government complaints about the press and calls to censor it even before the United States became a country. There was also a feisty, very partisan press. A partisan is someone who supports one political partys point of view and not the other. It is true of much of the media today. It is striking how similar the issues have been over the last two hundred years. Basic questions about freedom of the press have not changed. How does the press act as a watchdog against government abuses? Can freedom of the press exist in time of war without endangering national security? Why does it matter that different points of view are represented? From the beginning of our country, Americans have debated these questionsoften in the press itself.

They have also been debated in Supreme Court hearings and decisions. This book explores the way that the Supreme Court has helped interpret the meaning of freedom of the press over time. Challenges to total press freedom usually come through the courts, and their decisions are used to shape the decisions in newer cases. The controversial areas where the law sets limits to press freedom are national security, discrediting another person (libel), offending community values (this includes pornography), and incitement to violence based on hatred of a group because of race, politics, religion, or gender. Another question Americans ask is, are these limits valid or should there be no limits at all?

Often, the press reports information or opinions that we would rather not know or consider. Accepting ideas that we agree with is easy. Accepting the publication of ideas we dislike, fear, or believe damage our country or some of its peopleor that are negative about ourselvesis much harder. The principle of free thoughtnot free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hateis an important principle of the Constitution, wrote famous Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in 1929. That is the heart of press freedom: that everyone, even if we disagree strongly with them, has a right to be heard.

When the Founding Fathers came to create the Bill of Rights, they included freedom of the press because they believed that a democracy needs an active, vital press representing all points of view. They thought that the best way to preserve democracy was to encourage debate based on reading different accounts and opinions. Open discussion of ideas and their faults or merits would eventually lead to the best solutions for everyone. A free press would encourage Americans to think, argue, and defend all ideas. Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government, wrote Benjamin Franklin. When this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved.

The Founding Fathers also believed in a press that would be a watchdog over government. These were men who had rebelled against their rulers during the American Revolution because they believed the British government, led by the king and Parliament, was unfair. They wanted a press that would point out and criticize bad decisions rather than say only good things about leaders and lawmakers. One way to protect the people from government interference was to let them know when their political leaders were acting badly.

There is nothing so fretting