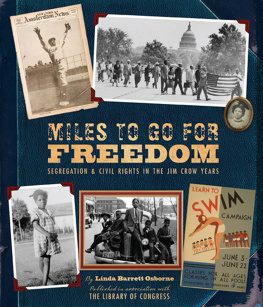

This poster was printed in the late 1930s to advertise swimming lessons given by the New York Department of Parks. Even though the lessons were open to all children, the design suggests that white children would be taught separately from black children.

To teachers and librarians, who pass on the legacy

of American history to their students, so that they can

better understand the past and shape a better future

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Osborne, Linda Barrett, 1949

Miles to go for freedom : segregation and civil rights in the Jim Crow years / by Linda Barrett Osborne.

p. cm.

Published in association with the Library of Congress.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4197-0020-0

eISBN: 978-1-6131-2206-8

1. African AmericansSegregationHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 2. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 3. Civil rights movementsUnited StatesHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 4. United StatesRace relationsJuvenile literature. I. Library of Congress. II. Title.

E185.61.O827 2011

305.896073009041dc23

2011022854

Copyright 2012 Library of Congress

Book design by Maria T. Middleton

For image credits, please see .

Excerpt on from Get Back (Black, Brown and White), words and music by William Lee Conley Broonzy 1952 (renewed 1980) SCREEN GEMS-EMI MUSIC INC. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. Used by permission.

Reprinted by permission of Hal Leonard Corporation.

Published in 2012 by Abrams Books for Young Readers, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

Abrams Books for Young Readers are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

115 West 18th Street

New York, NY 10011

www.abramsbooks.com

CONTENTS

These African American children, posed on a porch in Georgia, were photographed in 1899 or 1900, just three or four years after the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson declared that separating black and white people traveling on trains was legal. The children would grow up under a system of segregation that affected all aspects of their lives.

PREFACE

At fifteen, I was fully conscious of the racial difference, and while I was sullen and resentful in my soul, I was beaten and knew it, remembered Albon Holsey. He was an African American teenager in the early 1900s, growing up in the South. I knew then that I could never aspire to be President of the United States, nor Governor of my State, nor mayor of my city; I knew that the front doors of white homes in my town were not for me to enter, except as a servant; I knew that I could only sit in the peanut gallery [balcony] at our theatre, and could only ride on the back seat of the electric car.

Weve come a long way since Albon Holsey reflected on his future at the turn of the twentieth century. In the 1960s, African Americans began to be elected as mayor of cities both large and small. (There had been black mayors from the 1860s until the 1880s, before most black men lost the vote.) Carl Stokes was the first African American elected mayor of a big city, Cleveland, Ohio, in 1967. In 1989, Douglas Wilder was the first African American elected governor of a state, Virginia; and in 2006, Deval Patrick became the second black American to be elected governor, this time of Massachusetts. In 2008, Barack Obama became the first African American to be elected president of the United States.

But what was life like for Holsey and millions of other black Americans before the 1960s? In the South, they lived under a system of legal segregation, informally called Jim Crow, which defined and restricted their activities, their behavior, and their opportunities. Although many people believed that this had always been the southern way of life, African Americans had enjoyed some civil rights and a measure of freedom from the end of the Civil War in 1865 through the early 1890s. How and why did they lose this freedom? What was the impact of segregation on day-to-day life for black Americans, particularly for a young person? Did Jim Crow operate outside the South, in the northern, midwestern, and western states? How did federal policy affect segregation on a national level? How did African Americans fight back to regain their civil rights in the first half of the twentieth century?

This book considers these questions, focusing on the period between 1896, when the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson condonedthat is, approved or found acceptablethe notion of separate but equal public accommodations, and 1954, when it declared in Brown v. Board of Education that segregated schools could never be equal because their very existence as separate proclaimed that one race was better than another. Miles to Go for Freedom is a companion to my book Traveling the Freedom Road: From Slavery and the Civil War Through Reconstruction, which explores U.S. history and the lives of young black Americans from 1800 through 1877. This volume stops short of the protests and marches of the classic civil rights movement of the mid- to late-1950s and 1960s, which is covered by a large number of fine books for both children and adults.

For as long as African Americans have been oppressed, they have struggled for their civil rights. Many of the images and personal remembrances in this book capture the experiences of children and teenagers as they encounteredand tried to overcomeracism. Knowing how segregation developed and what it was like to live under that system links the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with the present in ways that illuminate both. This book cannot cover every topic and event of the Jim Crow years. But by broadening the scope to include Jim Crow as it was practiced not only in the South but in the rest of the nation, as well as by the federal government, it presents an overview of how African Americans lived in all parts of our country. It is not enough, however, to describe segregation and discrimination; it is equally important that Americans understand how African Americans resisted efforts to control and limit their lives, not just during the 1950s and 1960s but also as a continuous part of their history. A knowledge of these efforts and experiences is essential to understanding the civil rights movement that ended legal segregation; it is also key to understanding U.S. racial history, which still affects attitudes, policies, and politics today.