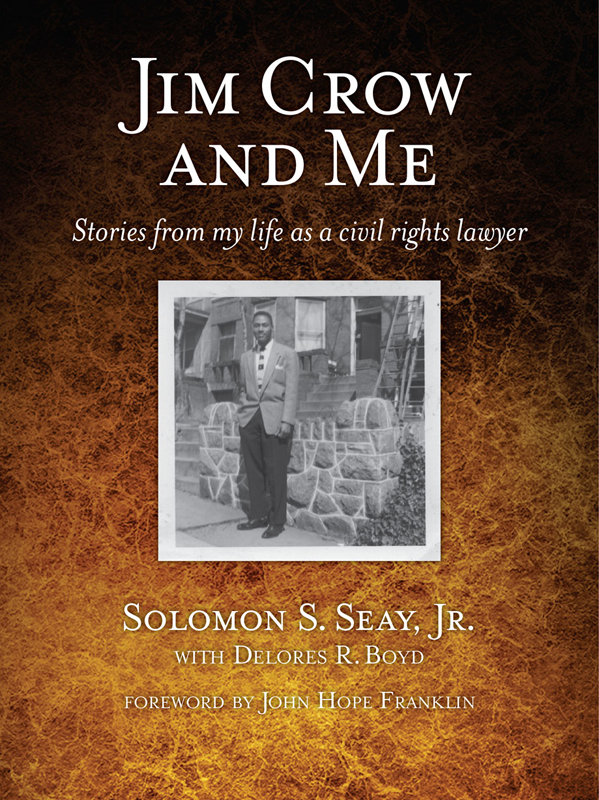

Solomon S. Seay, Jr.

with Delores R. Boyd

Copyright 2008 by Solomon S. Seay, Jr., and Delores R. Boyd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by NewSouth Books, a division of NewSouth, Inc., Montgomery, Alabama.

Visit www.newsouthbooks.com.

Jim Crow, the system of laws and customs that enforced racial segregation and discrimination throughout the United States, especially the South, from the late nineteenth century to the 1960s. Signs reading Whites Only or Colored hung over drinking fountains and the doors to restrooms, restaurants, movie theaters, and other public places. Along with segregation, blacks, particularly in the South, faced discrimination in jobs and housing and were often denied their constitutional right to vote. Whether by law or by custom, all these obstacles to equal status went by the name Jim Crow. Jim Crow was the name of a character in minstrelsy (in which white performers in blackface used African American stereotypes in their songs and dances); it is not clear how the term came to describe American segregation and discrimination. Jim Crow has its origins in a variety of sources, including the Black Codes imposed upon African Americans immediately after the Civil War and prewar racial segregation of railroad cars in the North. But it was not until after Radical Reconstruction ended in 1877 that Jim Crow was born.

excerpted from Africana: The Encyclopedia

of the African and African American Experience ,

Kwame Anthony Appiah and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., eds.

Solomon S. Seay, Sr. , 18991988

To the memory of my father,

The Reverend Solomon Snowden Seay, Sr.

And to the memory of my wife,

Ettra Spencer Seay

And also for the inspiration of

A Whale That I Never Saw

Ettra

(December 21, 1933May 28, 2006)

Always for me, beside me,

because of me.

My will, my way, my voice,

my needs, my choice.

Your dreams deferred

for mine...

they did not rot,

you did not explode...

No festering sores

ever scarred your soul.

From your heart flowed

endless love,

precious love,

only love.

Empowering, sustaining, and forgiving

me... ours...

somebodys child.

For your faithfulness...

I am here.

Sol

Laws for racial segregation had made a brief appearance during Reconstruction, only to disappear by 1868. When the Conservatives resumed power, they revived the segregation of the races. Beginning in Tennessee in 1870, white Southerners enacted laws against intermarriage of the races in every Southern state. Five years later, Tennessee adopted the first Jim Crow law, and the rest of the South rapidly fell in line. Blacks and whites were separated on trains, in depots, and on wharves. After the Supreme Court in 1883 outlawed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, the Negro was banned from white hotels, barber shops, restaurants, and theaters. By 1885 most Southern states had laws requiring separate schools. With the adoption of new constitutions the states firmly established the color line by the most stringent separation of the races; and in 1896 the Supreme Court upheld segregation in its separate but equal doctrine set forth in Plessy v. Ferguson.

excerpted from From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans ,

by John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr.

Contents

John Hope Franklin

As one who lived through the Civil Rights Movement and who participated in it on a limited basis, I am delighted to cheer along the Seay-Boyd collaboration. This is, indeed, an exciting joint effort, not unlike the project my son and I worked together when we published my fathers autobiography, My Life and an Era. It is virtually impossible to portray that period unless one had a special prism through which to view it or, at least, a vantage point from which to consider its momentous events.

I am surprised at the number of people who have, somehow, associated me with the day-to-day developments in the Tulsa, Oklahoma, race riots of late May and early June of 1921. I was not in Tulsa at the time and would not arrive there for the first time until May or June 1925. Meanwhile, my mother, younger sister, and I survived the suspense of not knowing for three or four weeks if my father was alive or among the charred bodies that lay on the roadways for days and even weeks after the shooting and looting had ceased. My older sister and brother were away in a boarding high school in Tennessee. When my mother, sister, and I reached Tulsa from Rentiesville in 1925, I was ten years old and in the seventh grade. My father, whose law practice was better than it had been when he moved to Tulsa just before the riot, was overjoyed that the family was together again.

As I read of the remarkable account of Solomon Seays struggles against Jim Crow in Alabama, I could not resist seeing the striking similarity that they bore to my fathers struggles in Oklahoma. Like Seay, my father fought Jim Crow whenever and wherever he found it. One notable example was the city ordinance against the use of certain flammable materials in construction, a sure effort to block rebuilding by poverty stricken blacks. My father took the case of one of his disobedient clients to the state supreme court, where the ordinance was declared unconstitutional. Then, there were the long afternoons I spent with him in his office, where there were few clients and I had an abundance of homework. I almost wished that clients would stay away, which would give me my fathers exclusive attention, even if it meant that he collected no fees from the very few clients who could afford to pay.

I do not believe that my dad ever met Solomon Seay, and the closest I got to him was in 1943 when I taught in the summer session of Montgomerys Alabama State College. It was the year that I saw patterns of segregation that must have strained the imagination of its creators. The most notable of these was at the state liquor store, where the line leading up to the counter was divided by a wooden wall; but the sales counter itself was common for both races, so that a single clerk could serve people on both sides of the racial divide.

It does not take more than a few minutes of scrutiny to discover that racial segregation represents one of the most creative and imaginative pursuits ever improvised by mankind. Even if the creative spirit was alive and well in shaping the sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages, it was no more creative than some of its contemporaneous colleagues whose creative imagination would doubtless be strained at times in making certain that the races would remain segregated.

I am delighted that Attorney Seay and Delores Boyd have decided to share their experiences with the general public. Her courage as well as her resourcefulness and ingenuity made his life a rich resource for all of us to emulate. For groups that have not yet broken the back of segregation in their lives and experiences, the battle of the Seays and Boyds is an ideal place to begin their own battle against racial segregation in their own lives.