Saving the Soul of Georgia

SAVING THE SOUL OF GEORGIA

DONALD L. HOLLOWELL AND THE STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

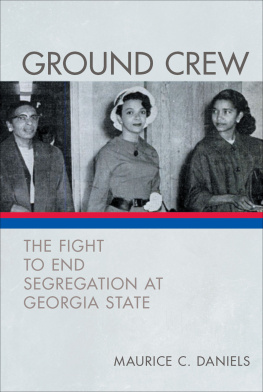

Maurice C. Daniels

Foreword by Vernon E. Jordan, Jr.

A Sarah Mills Hodge Fund Publication

This publication is made possible in part through a grant from the Hodge Foundation in memory of its founder, Sarah Mills Hodge, who devoted her life to the relief and education of African Americans in Savannah, Georgia.

2013 by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

All rights reserved

Set in Minion by Graphic Composition, Inc.

Manufactured by Thomson-Shore

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

17 16 15 14 13 c 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Daniels, Maurice Charles, 1952

Saving the soul of Georgia : Donald L. Hollowell and the struggle for civil rights / Maurice C. Daniels ; [foreword by] Vernon E. Jordan.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-4596-3 (hardback)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-4596-2 (hardcover)

1. Hollowell, Donald L., 1917-2004.

2. LawyersGeorgiaBiography.

3. African American lawyersGeorgiaBiography.

4. African AmericansCivil rightsGeorgiaHistory20th century.

5. African AmericansSegregationGeorgiaHistory20th century.

6. Civil rightsUnited States.

I. Title.

KF373.H597D36 2013

340.092dc23

[B] 2013017346

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN for digital edition: 978-0-8203-4629-8

To Carrin, Lauren, Nicole, Maya,

and to the memory of my brother, LaFronzo Daniels

Contents

Illustrations follow

Foreword

Vernon E. Jordan, Jr.

From the time of Donald L. Hollowells birth in 1917 to his death in 2004, black Americans faced what historian W. E. B. Du Bois called the problem of the twentieth centurythe problem of the color line. During Hollowells lifetime black soldiers fought in two world wars for a country that subjected blacks to second-class citizenship; state-sanctioned educational policies barred blacks from equal opportunities in public schools and colleges; an oppressive criminal justice system routinely denied blacks due process of law and the right to serve on juries; the health-care system prohibited blacks from access or relegated them to inferior treatment; and blacks faced systemic racial discrimination in areas such as employment, housing, public accommodations, transportation, and voter registration. Yet Hollowell also saw a massive social movement transform the racial landscape of America, along with the signing of executive orders and passage of numerous laws to ensure civil rights. His life was a testament to the struggles of black Americans in the twentieth century, struggles in which he figured prominently. Hollowells long and illustrious career as an attorney and freedom fighter in the American South spanned the entire second half of the twentieth century.

I learned of Donald Hollowells reputation as a civil rights lawyer when I was a young man growing up in Atlanta in the 1950s. Back then Hollowell was affectionately known as Mr. Civil Rights, a man who combined his interest in law with his passion for social justice. After moving to Atlanta in 1952, he became actively involved in community organizations such as the NAACP, and his activism in the community complemented his courtroom efforts to win civil rights for blacks.

As a Howard University law student who dreamt of returning home to practice civil rights law, I set my sights on securing a job in my hometown with one of the few Georgia lawyers who acted as cooperating attorneys for the NAACP, serving as local counsel when the Legal Defense Fund (LDF) pursued cases in the area. Kenneth Days, my bandmaster at David T. Howard High School and a friend and fraternity brother of Hollowell, encouraged Hollowell to meet with me when I came home for Christmas break in 1959. I saw firsthand in that meeting how committed he was to social justice and civil rights.

I started working for Hollowell for thirty-five dollars a week in May 1960, a few days after I graduated from law school. He was taking on cases in Atlanta while at the same time crisscrossing Georgia to defend blacks in remote locales and to assist the LDF in obtaining equal rights for blacks in public schools, public accommodations, voting, and many other areas. Amazingly, he had been a sole practitioner without a law clerk for eight years. Hollowell desperately needed help, so when I joined his law office I became his law clerk, researcher, legal interlocutor, and chauffeur. Being in close contact with the man for many hours, I learned what I could not have learned in law school. I learned not only the craft of being a lawyer but also how to successfully navigate a judicial system that had little regard for black attorneys and accorded even less respect and fairness to black clients.

Many days and nights I traveled with Hollowell to the backwoods outposts and urban centers of Georgia, defending the rights of numerous black men unjustly charged with crimes under the Jim Crow system. One case in particular that Maurice C. Daniels covers in detail in of this biography is that of Nathaniel Johnson, a black man sentenced to die for allegedly raping a white woman. Hollowell rushed to help after Augusta NAACP president Reverend C. S. Hamilton called to inform him that Johnson was incarcerated in the Tattnall County State Prison awaiting execution.

In a hearing the day before the scheduled execution, I stood with Hollowell in the U.S. courthouse of the Southern District of Georgia before avowed segregationist Judge Frank Scarlett, seeking a stay of execution for Johnson. Hollowells most reasoned arguments failed to move Judge Scarlett. In the ensuing twenty-four hours I witnessed Hollowells remarkable commitment to his client and his relentless determination to see that justice was served. I also saw his extraordinary compassion for his client as he meticulously and exhaustively pursued every possible legal avenue trying to save Johnsons life.

I learned vital lessons from Hollowells humanity and compassion in this case, lessons that guided me in my legal practice and continue to serve as a model for my actions today. Equally instructive were Hollowells lessons about preparation, tenacity, and perseverance as a legal advocate. And from this case, I acquired an intimate understanding of Hollowell the man, the humanitarian, the legal scholar and theorist, the tactician, and the pragmatist.

From this case on, I continued to watch carefully and to learn many valuable lessons that shaped the lawyer and the man I am today. I assisted Hollowell with dozens of cases in Atlanta and throughout Georgiacases involving the defense of black people often charged with capital crimes and precedent-setting cases that challenged the Jim Crow system in the context of the Fourteenth Amendment. The most celebrated case asserting equal justice under the law on which I assisted Hollowell was Holmes v. Danner, in which Hollowell and his clients fought to desegregate the University of Georgia (UGA).

Daniels provides a rich and well-documented account of that case in . Hollowell, as an activist lawyer, played a key role in selecting Hamilton Holmes and Charlayne Hunter, two brilliant young students from Atlanta, to seek admission to UGA in 1959. The state of Georgia at that time used every available ploy to sustain segregation in its institutions, and UGA was no exception. Holmes and Hunter were summarily rejected by university officials, and Hollowell ultimately filed a lawsuit to gain their admission.

Next page