Contents

Guide

Page List

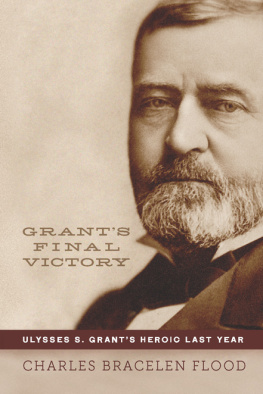

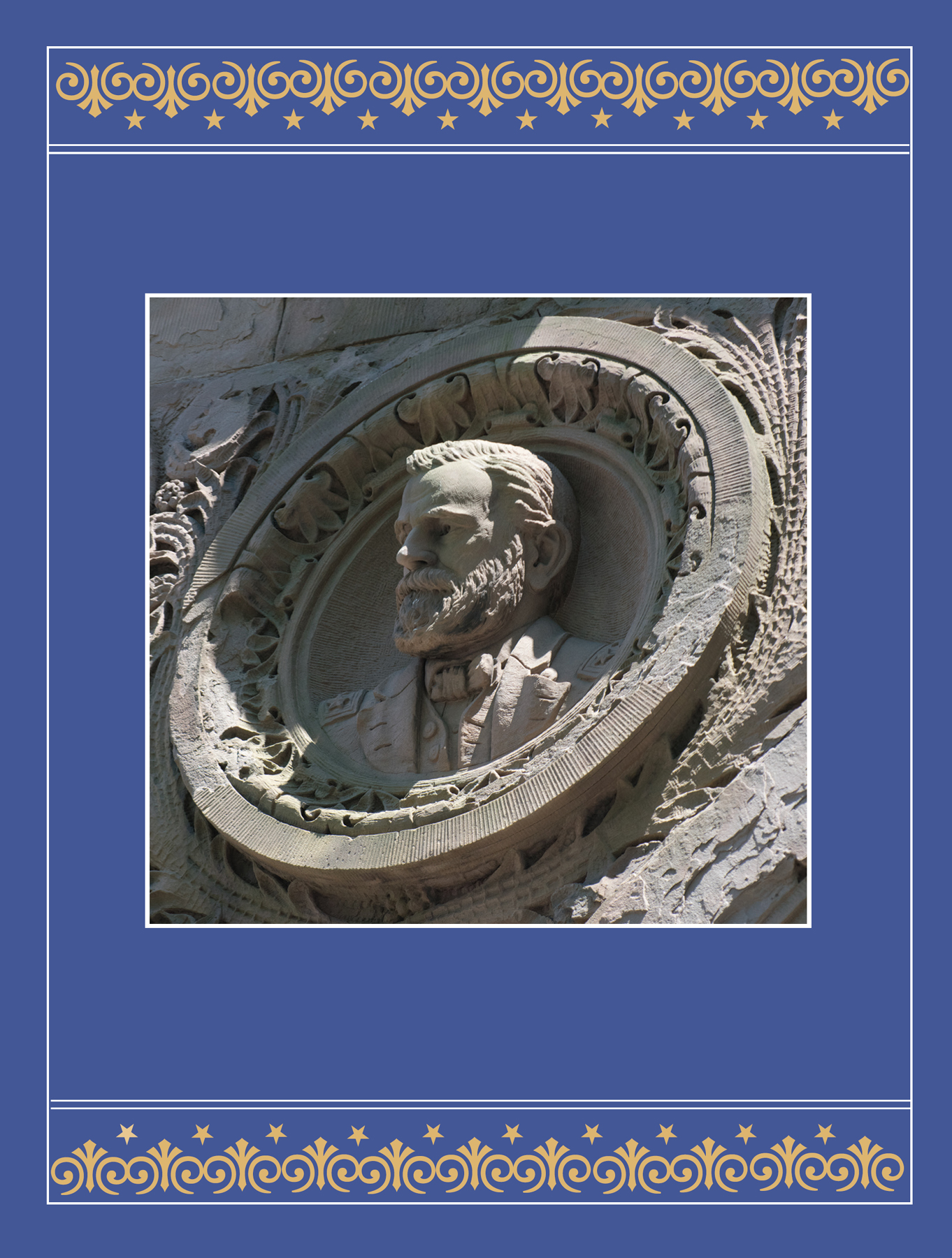

Bust of Ulysses S. Grant, faade of former Union League Club, Brooklyn, New York. Photograph by Elizabeth D. Samet.

Yet to me he is a mystery, and I believe he is a mystery to himself.

William T. Sherman on Ulysses S. Grant (1879), The Century Magazine (1897)

Gertrude Stein and Sherwood Anderson... found out that they both had had and continued to have Grant as their great american hero. They did not care so much about Lincoln either of them. They had always and still liked Grant. They even planned collaborating on a life of Grant. Gertrude Stein still likes to think about this possibility.

Gertrude Stein, The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933)

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

Charles Dickens, David Copperfield (1850)

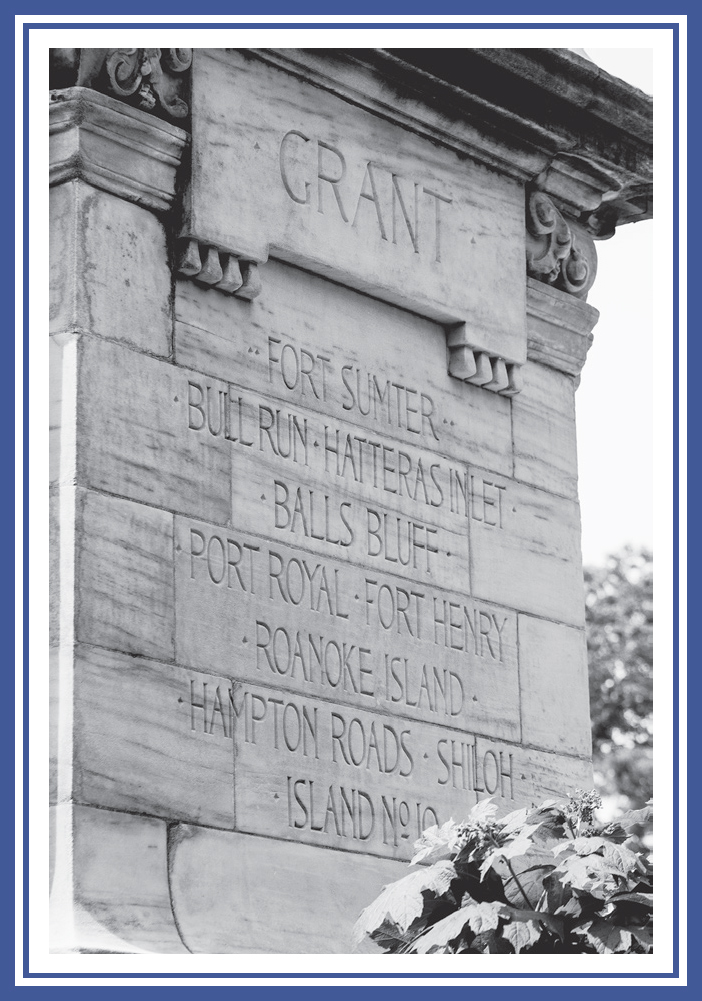

Grant Plinth, Soldiers and Sailors Monument, New York, New York. Photograph by Elizabeth D. Samet.

Contents

Text of Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant

W hen people ask me how I came to teach at West Point, I usually provide the short answer: My father and Ulysses S. Grant. Were it not for my fathers experience as a sergeant in the Army Air Corps during World War II, together with my accidental discovery while in graduate school of Grants Personal Memoirs, I suspect the prospect of teaching literature to aspiring army officers would have heldto borrow Grants own characterization of his feelings toward military life as he journeyed from Ohio to West Point for the first timeno charms for me.

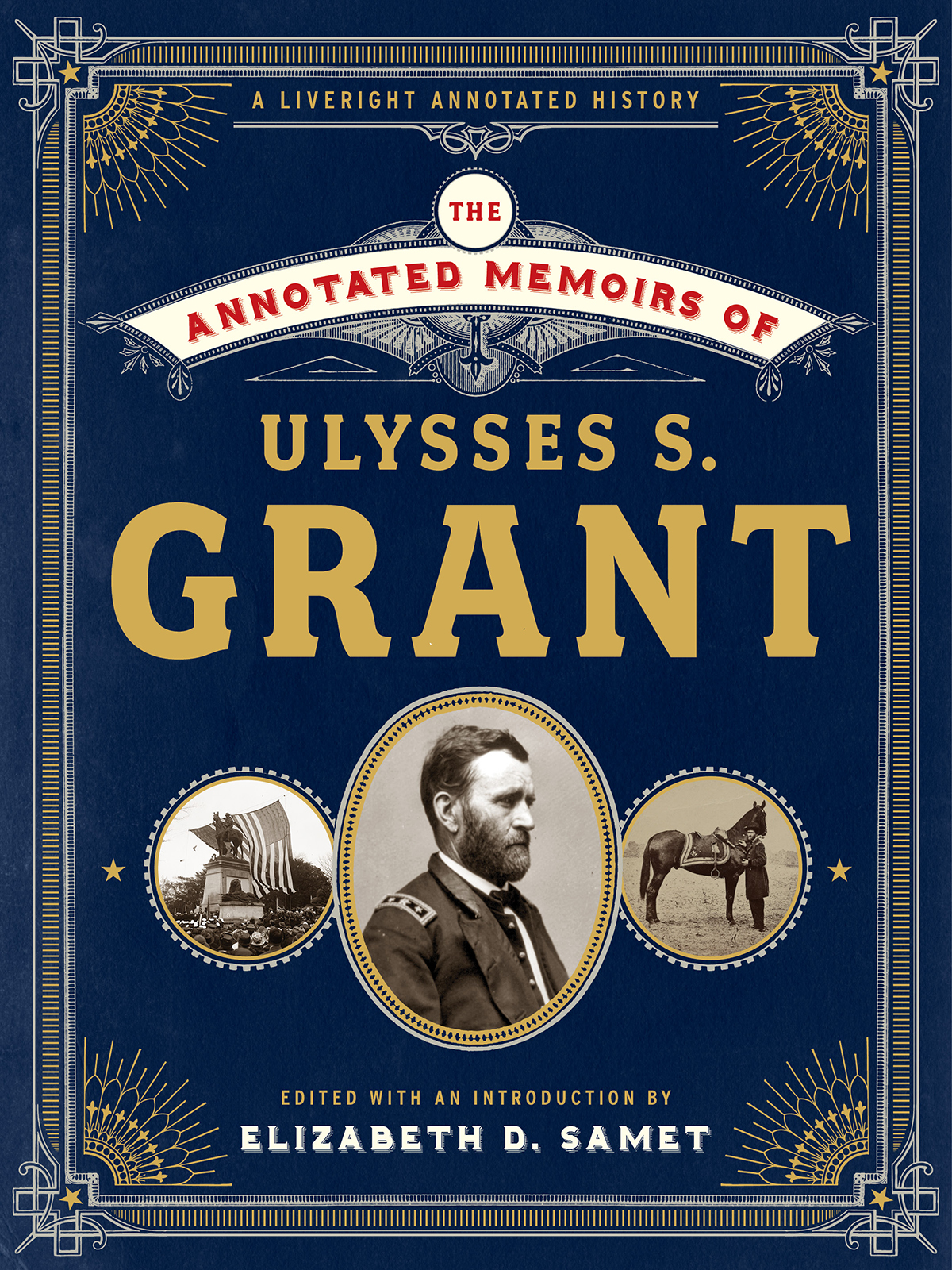

The long answer can be found in this book, for which I have unwittingly been preparing for years. During that time Grant has been my Virgil, his words a priceless guide to aspects of military culture as well as to the various social, political, and literary legacies of nineteenth-century America with which we continue to grapple today. I seek to share many of those illuminations in this edition of Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, which was first published in 18851886 by the firm of Charles L. Webster, in which Mark Twain was a partner. Here the reader will encounter Grants words side by side with my annotations as well as with a wide-ranging selection of maps and other images of my choosingand, in the case of some of the photographs, my making. Photography offered me another way to reckon with the interpretations of the Civil War that continue to texture the present moment. The notes and illustrations situate the memoirs in several contexts: military and historical, of course, but also literary, cultural, social, and political. This edition offers new insights into Grants experience at West Point, where I have taught since 1997; presents previously unpublished archival material and images; and expands in both place and time the typical Civil War backdrop against which Grants story is usually read.

Long recognized as a landmark military memoir, Grants book has been edited primarily by historians, for whose expertise I am deeply grateful. The editors William S. McFeely and Mary Drake McFeely, James M. McPherson, and John F. Marszalek and his team at the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library at Mississippi State University have all illuminated vital aspects of the text and its author. Yet Grants Personal Memoirs is also a significant work of American literature and a defiantly atypical narrative of war, if in certain respects a conventional expression of nineteenth-century attitudes. From my vantage point as a literary scholar I strive to do something new here by presenting the text as not merely an exemplary military memoir but an indispensable part of the robust tradition of American autobiography, which extends from the spiritual autobiographies of the colonial period to the confessional memoirs of the present day. Grants book is a significant contribution to our national literature.

Thus while I strive to be scrupulous about historical and military matters, I am also invested in the complex linguistic and cultural tapestry of nineteenth-century America. It is not a particular event alone but the ways in which Grant and his contemporaries remember and choose to depict it that primarily engage me. Although, as I have suggested, much of Grants thinking is clearly of its time, his book is utterly remarkable in its rejection of the deeply romantic, heavily sentimental mode of most nineteenth-century Civil War reminiscences. In order to illuminate this most radical aspect of the book, my notes often provide passages from other writers, which are meant to be read in parallel with Grants text. Often these are contemporaneous recollections of identical, or comparable, events. But I have also drawn from different eras, cultures, and genres to illustrate the long tradition of war writingfiction and poetry as well as nonfictionand to place Grants book along a continuum of written representations of war from antiquity onward.

One of the most noteworthy aspects of Grants book is its style. Reviewing a volume of his letters in 1898, Henry James described the prose as having a hard limpidity. Grants correspondence sounded an old American note, James explained. Its austerity conveyed the sense of the hard life and the plain speech.

The ongoing national conversation about the meaning of the Civil War reveals the enduring influence of this revisionist campaign. Its mendacious rhetoric, polished and perfected over the years, has succeeded in masking uncomfortable truths by ignoring slavery and fetishizing states rights and by giving moral authority to both sides of the conflict by placing a premium on physical courage, sacrifice, and a very particular concept of honor. Postwar rhetoric revised the Souths own clearly stated motivation for secessionpreserving the right to enslave human beingswhile its obsessive focus on federal tyranny ignored the slave states antebellum enthusiasm for federal power when, for example, it was enlisted to enforce the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. The canonizing of Southern heroes, which intensified in the post-Reconstruction era, served to cloak with sentimental ritual the programmatic social and political injustice of Jim Crow. The battles being fought today in the media and on the streets of American cities and towns over Confederate commemoration are the reckoning for more than a century-long perversion of Civil War memory. There is no more fitting time to revisit the memoirs of the man Lincoln ultimately entrusted to win the war on the battlefield.