Table of Contents

PENGUIN

CLASSICS

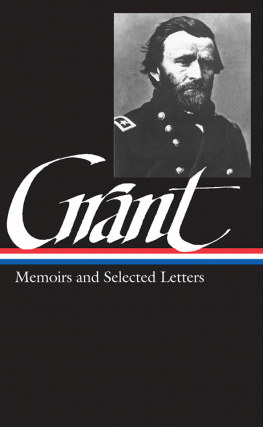

PERSONAL MEMOIRS OF U . S . GRANT

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, the son of a tanner, Jesse Root Grant, and Hannah Simpson Grant. Grant worked on the family farm and attended local schools until his appointment in 1839 to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. (The young cadet was erroneously registered as U.S. Granta change that Grant would adopt for the rest of his life.) Commissioned second lieutenant in the Fourth Infantry Regiment, Grant served in the Mexican War (1846-48) under Generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. Having resigned the army in 1854, Grant spent the next six years farming and undertaking various unsuccessful business ventures. After the outbreak of the Civil War, the governor of Illinois appointed Grant colonel of a militia regiment in June 1861; two months later he was promoted to brigadier general. Placed in command of the District of Southeast Missouri, with headquarters in Cairo, Illinois, Grant led the expedition that captured Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, and a Confederate force of some 15,000 in February 1862. Promoted to major general of volunteers, Grant led the Union forces at Shiloh in April 1862 and at Vicksburg the following year; with the fall of Vicksburg (July 1863), Grant was made a major general in the regular army. After leading the victories in November at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general with command of all the armies of the United States in March 1864. In May, Grant launched the final campaign, sending General Sherman toward Atlanta and directing the Army of the Potomac against General Robert E. Lees Army of Northern Virginia. The grueling war of attrition that followed wore the Confederates down, and Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865. Grant was elected president of the United States in 1868 and reelected in 1872. Though scrupulously honest himself, Grants administration was marked by widespread corruption and serious scandals. On retiring from office in 1877, he made a world tour on which he was hailed as a hero. Encouraged by his friend Mark Twain, Grant began preparing his memoirs in 1884. The Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant were completed just a few days before his death on July 23, 1885.

James M. McPherson is the George Henry Davis 86 Professor of American History at Princeton University, where he has taught since 1962. He is the author of a dozen books on the era of the American Civil War, and has won the Anisfield-Wolf Award for The Struggle for Equality: Abolitionists and the Negro in the Civil War and Reconstruction (1964); the Pulitzer Prize in history for Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988); the Lincoln Prize for For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (1997); and with his wife, Patricia McPherson, the Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt Prize in Naval History for Lamson of the Gettysburg: The Civil War Letters of Lieutenant Roswell H. Lamson, U.S. Navy (1997).

INTRODUCTION

Grants Personal Memoirs are perhaps the most revelatory autobiography of high command to exist in any language, according to the astute British military historian and analyst John Keegan. If there is a single contemporary document which explains why the North won the Civil War, that abiding conundrum of American historical inquiry, it is the Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. This is strong praise, especially coming from a non-American. And Americas greatest novelist as well as its foremost literary critic anticipated this encomium. Edmund Wilson in 1962 reaffirmed Mark Twains 1885 judgment that the Personal Memoirs were the most remarkable work of its kind since the Commentaries of Julius Caesar.

What made the Personal Memoirs so remarkable? And how does this book explain why the North won the Civil War? The first clue to an answer for these questions concerns the conditions under which Grant wrote the Personal Memoirs. For several years after he left the presidency in 1877, Grant resisted pressure to record the story of his war experiences as other Civil War generals had already donemost notably William Tecumseh Sherman, whose Memoirs had appeared in 1875 with great fanfare. Grant protested that he had little to say and less literary ability to say it. He had always been loath to speak in public and equally reluctant to write for the public. As president from 1869 to 1877, he had confined his communications to formal messages, proclamations, and executive orders drafted mainly by subordinates.

From 1877 to 1879, ex-President Grant and his wife, Julia, traveled around the world. As the most famous living American, Grant was welcomed and feted by royalty and heads of state everywhere he went. After he returned to the United States, he bought a brown-stone in New York City and settled down at age fifty-eight to a comfortable retirement. He invested his life savings in a brokerage partnership formed by his son Ulysses, Jr., and Ferdinand Ward, a Wall Street wizard who was known as the Young Napoleon of Finance. Unknown to Grant, some of Wards ventures were highly speculative and others turned out to be fraudulent. In 1884 this house of cards collapsed. Ward went to jail and left Grant with $150,000 in debts and a total of $180 in the bank. Determined to repay his debts (even though his creditor, William Vanderbilt, was willing to cancel them), Grant now needed remunerative employment. In the summer of 1884, therefore, he accepted an offer of $500 per article from Century magazine to write four articles for their series Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. These articles on the battles and campaigns of Shiloh, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and the Wilderness became the nucleus of the Personal Memoirs.

When I put my pen to the paper I did not know the first word that I should make use of in writing the terms. I only knew what was in my mind, and I wished to express it clearly, so that there could be no mistaking it. These sentences describe Grants feelings when he sat down with Robert E. Lee in Wilmer McLeans parlor at Appomattox to write out the terms of surrender for the Army of Northern Virginia. They could serve equally well to describe his feelings as he sat down to write the first of the Century articles, on Shiloh. Yet just as he expressed the terms of surrender in terse, vigorous, lucid prose, so his Century articles revealed a previously unsuspected talent for pithy, vivid narrative exposition. I only knew what was in my mind, and I wished to express it clearly. Here was the secret of Grants remarkable success as a writer. No better advice could be given to any aspiring author.

The money that Grant earned for the Century articles would not go far toward paying his debts. And while working on these articles, Grant began to experience severe throat pains. In October 1884 he learned that he had throat cancer, incurable and fatal. This was a potentially tragic blow. But Grant rose above it, just as he had overcome the initially successful Confederate breakout attack at Fort Donelson, the enemys apparent victory on the first day at Shiloh, the failure of his first attempts to get at Vicksburg, the bloody repulse of attacks at Cold Harbor and Petersburg, and other apparent defeats that he converted to victories in the war.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS