Trimming Yankee Sails

Pirates and Privateers of New Brunswick

The New Brunswick Military Heritage Series, Volume 6

TRIMMING YANKEE SAILS

Pirates and

Privateers

OF NEW BRUNSWICK

FAYE KERT

Copyright Faye Kert, 2005.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Marc Milner.

Cover illustrations: front: detail from Capture of Snap Dragon, by Irwin John Bevan (MM); Back:

Saint John from the Signal, 1841, by Charles Cousen (NBM).

Cover and interior design by Julie Scriver.

NBMPH cartographer: Mike Bechthold.

Printed in Canada.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kert, Faye

Trimming Yankee sails: pirates and privateers of

New Brunswick / Faye Kert. (New Brunswick military heritage series; 6)

Co-published by the New Brunswick Military Heritage Project.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86492-442-9

1. Pirates New Brunswick History. 2. New Brunswick

History 1784-1867. I. New Brunswick Military Heritage Project

II. Title. III. Series.

FC2471.9.P57K47 2005 971.5102 C2005-904697-X

Published with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the New Brunswick Culture and Sport Secretariat. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

GOOSE LANE EDITIONS

469 King Street

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 1E5

www.gooselane.com | NEW BRUNSWICK MILITARY HERITAGE PROJECT

Military and Strategic Studies Program

Department of History, University of New Brunswick

PO Box 4400

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3C 1M4

www.unb.ca/nbmhp |

To all those would-be privateers, rascals and rebels

you know who you are.

Contents

New Brunswicks Undeclared War, 1812

At War at Last, 1813-1814

The Chesapeake Affair, 1863-1864

The Legacy

Trimming Yankee Sails

Pirates and Privateers of New Brunswick

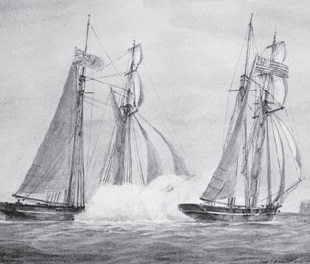

The Bream and the Pythagoras, by Irwin John Bevan. ( MM )

Introduction

I IMPLORE the Protection of the British Naval Commander, I am taken by Pirates, and have Government Stores on board, bound to Camden.

Captain D. MWaters, sloop Mary

1 November 1814

On November 1, 1814, the Saint John-owned sloop Mary lay in Camden harbour, on the coast of Maine, where she was boarded by six armed United States revenue officers. In ordinary times this was to be expected. But by November 1814 the US and Britain had been at war for two years, and the revenue officers had come aboard from a lowly rowboat. Perhaps this was why, when the British frigate HMS Furieuse, Captain William Mounsey, RN, in command, hove in sight, David MWaters, Marys master, slipped Mounsey a note complaining of his capture by pirates and pleading to be saved. MWaters even offered his captors 7,000 ransom for the sloop and volunteered to stand hostage for the money. In spite of this, he was publicly accused by one of the ships owners of signalling his Camden captors to seize the vessel so that he might also profit from their piracy.

It appears that Mary had indeed been captured by Americans after all: in the court process that followed, MWaters was proven innocent by the sworn statements of the his captors, Marys officers, passengers and crew. His worse offence seems to have been that he mistook Camden for Castine, where he was bound with supplies for the British occupying force. But MWaters still had to publish his denials in the local Saint John papers to clear his name. The accusation that he had conspired to have his ship and cargo captured was a crude attempt by one of the sloops owners, Gabriel Fowler, to force MWaters to pay for the owners loss. The character assassination, court testimony and newspaper stories involved MWaters and Marys owners, Fowler and Benjamin Darling of Saint John, New Brunswick, in a lengthy wrangle that outlasted the War of 1812.

The fact that MWaters had to work so hard to clear his name speaks volumes for the acceptance of such collusion between apparent enemies and the grey legal area of capture at sea. Indeed, as in all areas where international borders cut across economic and social interests, piracy, privateering, smuggling and arranged capture were all employed by entrepreneurial New Brunswickers in the nineteenth century. The Bay of Fundy, the Gulf of Maine and the waters of the western Atlantic were all part of a tightly interconnected seafaring community. When formal war, like the War of 1812, interrupted those familiar trading and social patterns, people on both sides adapted and situations at sea were not always what they seemed. American ships took out licences to continue trade with the British Empire, which was very much in need of American grain. Small traders flew false flags in order to deceive naval patrols and privateers, or if they were privateering vessels to trick an intended prize. And, in some cases, as was alleged with the sloop Mary in November 1814, capture could be arranged with friends in the other country so the prize and her cargo could be bought back cheap at auction inside the enemy blockade and the goods then resold by a local agent for a handsome profit for everyone. Mistaken identity, collaborating with the enemy, false colours, phony captures, smuggling, blockade running and profitable prize making were all part of New Brunswicks daring and devious nineteenth-century maritime history.

Private war at sea was a feature of every naval war and colonial conflict from the late medieval period until it was banned by international agreement in 1856 at least by every developed nation except the United States: they continued the practice until after their Civil War in the 1860s. The waging of private war at sea developed in an era when kings did not have navies in the modern sense and there were few means for either attacking an enemy at sea during war or recouping commercial losses due to enemy action. Since traders owned fleets of ships armed for protection against pirates, it was a simple matter for the King to issue his subjects with Letters of Marque and Reprisal, making them privateers. These commissions granted civilians the legal right to both wage war on the enemy and, in the process, to recover their own costs or commercial losses to enemy war vessels. A very fine line separated pirates from privateers, but that line, often no thicker than the paper on which a letter of marque was written, entitled the privateer to wage war on the enemy of his state and to keep most of the proceeds from the vessels he captured, his prizes. A pirate doing the same thing without a licence would be hanged.

Privateers were also obliged to follow strict rules for disposing of their captures: they had to be taken to a port that had a Vice-Admiralty Court, and the legality of the capture had to be proven before a judge. Once the judge ruled that the prize was good and lawful, the ship and/or cargo would be sold at auction and the proceeds shared among owners, officers and crew according to their pre-cruise agreement. Since Royal Navy vessels were also entitled to prize money and naval officers counted on prizes to supplement their salaries, public and private armed vessels frequently found themselves competing for captures.

Next page