The Charity Market and Humanitarianism in Britain, 18701912

Also available from Bloomsbury:

War, Law and Humanity: The Campaign to Control Warfare, 18531914, by James Crossland

Leisure, Voluntary Action and Social Change in Britain, 18801939, by Robert Snape

Female Philanthropy in the Interwar World: Between Self and Other, by Eve Colpus

Contents

This project was generously funded by the ESRC (Grant number: ES/I031359/1). It originated in a number of conversations between Julie-Marie Strange and Bertrand Taithe and from their collaboration over a number of years. Both have had a strong interest in charities and humanitarian aid respectively; they also share a common enthusiasm for the Victorian era. Together they brought their initial concerns for the material culture of charity into a research question. Dr Sarah Roddy joined in, initially as the research assistant for this project, but she soon became one of the three co-authors, bringing to the project her own considerable scholarship. All chapters were debated and written collectively as were the various articles originating from this project and which develop more fully some aspects of the work. In particular we are grateful to the Journal of British Studies for allowing us to use some of the material that appeared in our article of January 2015, The Charity-Mongers of Modern Babylon: Bureaucracy, Scandal, and the Transformation of the Philanthropic Marketplace, c.18701912.

This work has been grounded in ongoing discussions with contemporary NGOs and in the work done through the Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute (hcri.ac.uk) at the University of Manchester and in collaboration with the Overseas Development Institute. We have benefited greatly from the insights arising from our discussions with colleagues at ALNAP or at the Centre de Reflexion sur les Actions et les Savoirs Humanitaires (CRASH) at MSF. For some of the policy implications of this research we invite our readers to consult our article Humanitarian Accountability, Bureaucracy, and Self-Regulation: The View from the Archives? (Disasters, 39 [2015], 188203) or the article co-authored by Bertrand Taithe and John Borton: History, Memory and Lessons Learnt for Humanitarian Practitioners (European Review of History: Revue europenne dhistoire, 23 [2016], 21024).

Over the lifespan of the project we have had the opportunity to present aspects of this research to a variety of audiences, and we wish to thank particularly the feedback we received from colleagues at research seminars at universities in Manchester, Exeter and the Institute of Historical Research; the Material Religion in Modern Britain conference, Cardiff (2012); a workshop on History, Consumption and Inequality, Cambridge (2013); the Humanitarian Congress, Berlin (2014); the Humanitarian Studies Conference, Istanbul (2013); an MSF workshop in Paris (2015); the Modern British Studies Conference, Birmingham (2015); and the Voluntary Action History Society conference, Liverpool (2016).

We are blessed to be working in a remarkably fast moving and creative research environment in which an extraordinary number of colleagues, past and present, have cognate research interests that have fed into this project: among them, Eleanor Davey, Pierre Fuller, Peter Gatrell, Max Jones and Peter Yeandle. They have all contributed significantly to this project (whether they like it or not!). Of course, any errors remain ours entirely.

We wish to thank the archivists, curators and librarians of the following institutions: Barclays Bank Archive, Dr Barnardos Archives, Birmingham Archives, Birmingham Museum, the Borthwick Institute York, the British Library, Devon County Archives, Greater Manchester County Record Office, John Rylands Library, Lambeth Palace Library, Lancashire Record Office, Lancaster City Museum, Liverpool Catholic Diocesan Archives, Liverpool Record Office, London Metropolitan Archive, National Archives at Kew, National Army Museum, National Coal Mining Museum, National Railway Museum, Norfolk Record Office, Northumberland Museum, Salvation Army International Heritage Centre, Salford Diocesan Archives, Scottish National Archives, School of Oriental and African Studies Library, Staffordshire County Record Office, Tameside Local Study and Archive, Tyne and Wear Museum, University of Liverpool Special Collections, V&A Theatre Museum and West-Yorkshire County Archives. We owe a particular debt to the librarians of the John Rylands Library and of Saint Deiniols Library where this book first took its final shape.

This book took longer than we anticipated but it is, if anything, more relevant today than we expected when we first devised it.

Sarah Roddy, Julie-Marie Strange and Bertrand Taithe

Manchester, 2018

| The Army | Salvation Army |

| BBC | British Broadcasting Corporation |

| COS | Charity Organisation Society |

| IBVS | Indigent Blind Visiting Society |

| LWD | League of Welldoers |

| NSPCC | National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children |

| NWBH | National Working Boys Home |

| RSPCA | Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals |

| Stafford House Committee | Stafford House Committee for the Relief of Sick and Wounded Turkish Soldiers |

| Waifs and Strays Society | The Church of England Incorporated Society for Providing Homes for Waifs and Strays |

| WSM | Wood Street Mission |

| YHL | Young Helpers League |

| YMCA | Young Mens Christian Association |

An American with a reputation as the worlds record money collector arrived for a tussle with London at the beginning of 1912. Charles

But while journalists had been right to point out the novelty of Sumner Wards short period fundraising in a British context, of late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain were at least the equal of any contemporary American philanthropic expert.

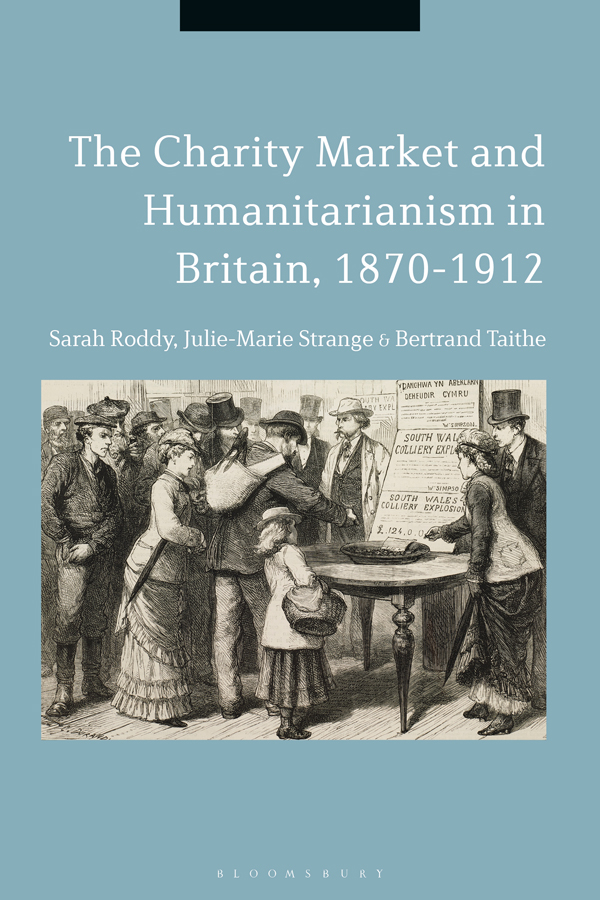

They had to be. During the Victorian era, the British charity scene altered dramatically. The tangle of endowments, trusts and parish-based ladies bountiful that characterized the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries did not disappear but they were joined by a recognizably modern charity market, in which increasingly professional collecting or voluntary charities, which derived their income from subscriptions and donations (rather than the proceeds of large endowments), predominated. This is not to imply that no such charities had existed before. But by 1870, we suggest, a critical mass had been reached, in part because parallel social and technological developments facilitated their foundation, growth and endurance. These more permanent organizations were joined by an increasing preponderance of one-off funds for causes at home and abroad, generally fatal catastrophes of one sort or another, which themselves adopted new technologies in their pursuit of donations.

The resulting intense competition for donors among these funds and organizations, we contend, drove many of them to greater heights of innovation in their fundraising practices. It created, in effect if not in intent, a charitable fundraising market. This charity market was characterized by competition for consumers (i.e. donors) among charity entrepreneurs. It involved conscious adoption by them of surprisingly up-to-date marketing techniques and strategies to sell and distinguish their particular brands of compassion from those of rivals with similar relief remits. It arose organically, as each new enterprise was set up by motivated individuals to tackle a perceived evil of modern industrial society, from child poverty to unemployment, and intemperance to immorality. It was in many ways a classically free market, unfettered by state intervention, although an invisible hand of self-regulation imperfectly contained the inevitable frauds and misconducts that even compassionate markets were wont to generate.