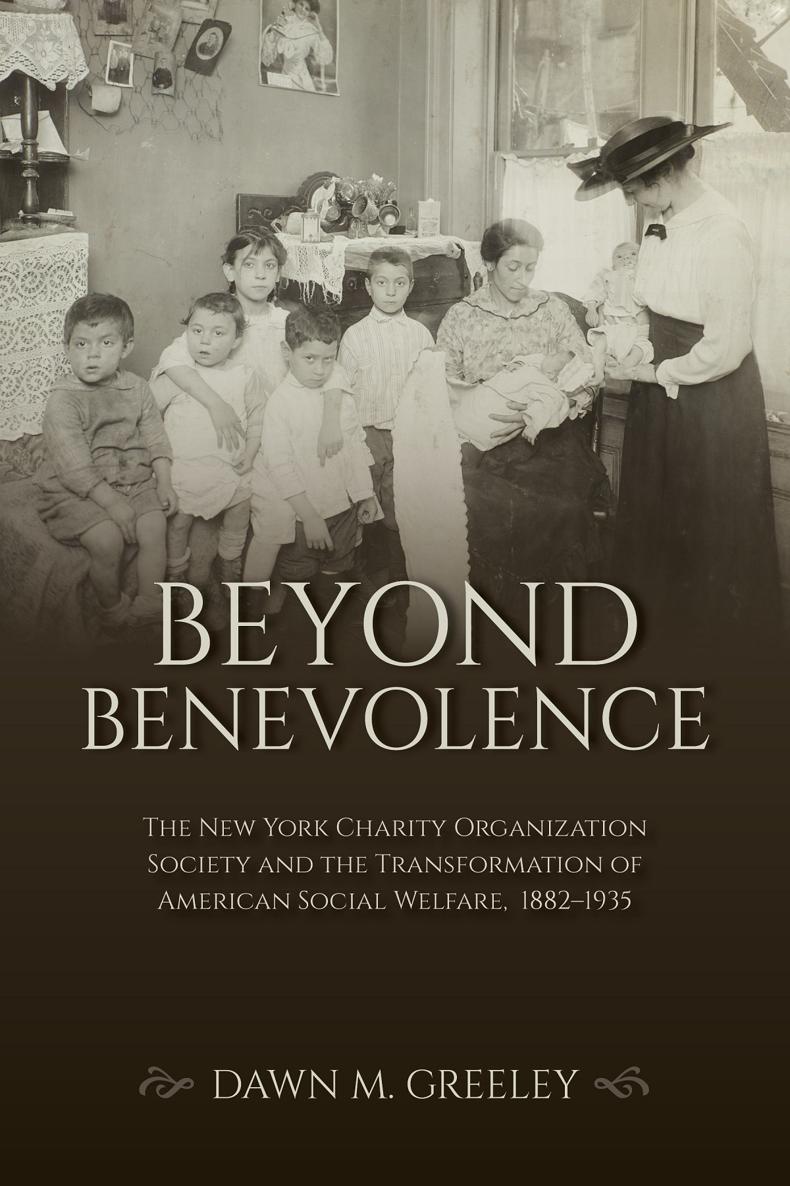

BEYOND

BENEVOLENCE

PHILANTHROPIC AND NONPROFIT STUDIES

Dwight F. Burlingame and David C. Hammack, editors

BEYOND

BENEVOLENCE

The New York Charity Organization Society and the Transformation of American Social Welfare, 18821935

Dawn M. Greeley

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2022 by Dawn M. Greeley

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-05909-3 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-253-05910-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-253-05912-3 (ebook)

First printing 2022

For Ed and Emily and in memory of my parents, Georgette and Gabriel

CONTENTS

1. Not Alms but a Friend: The Moral Economy of Scientific Charity

2. Organizing Charity in the City of Strangers: The New York COS

3. Neither Alms nor a Friend: Organizational Obstacles to the Practice of Scientific Charity

4. Hoping for Your Kind Interest: Donors, Clients, and the Uses of Scientific Charity

5. I Beg to Call Your Attention to a Very Deserving Case: Entitlement, Respectability, and the Politics of Charity in Working-Class Communities

6. If Not a Friend, Then Alms: Relief and Reform in the Progressive Era

7. The COS and the State: Widows, Deserted Wives, and the Battle over Mothers Pensions

8. From Friendly Visiting to Social Casework: The Triumph of Professionalism

Conclusion: The New York COS and the Transformation of American Social Welfare

Notes

Selected Bibliography

Index

THIS BOOK HAS BEEN A long time in the making. And while I have spent countless solitary hours bringing it to fruition, as this extended journey comes to an end, I am profoundly aware that I did not reach this point alone. With more than twenty years separating its initial incarnation as a dissertation and its reincarnation as a book manuscript, this project has occupied two very distinct phases of my life. At each of these junctures, I have received crucial personal and professional support from a variety of friends, family members, colleagues, and mentors. It gives me great pleasure to acknowledge them here.

I have benefited immeasurably from the collective wisdom of all those who read and commented on different aspects of this project at various stages of its development. Nancy Tomes was a superb dissertation advisor, whose steady hand guided me through every aspect of the initial research and writing process. I am deeply grateful for her thoughtful insights, unfailing support, and easy humor. I am also indebted to the other members of my dissertation committeeWilbur Miller, William R. Taylor, and Kathryn Kish Sklarwho provided invaluable advice, encouragement, and guidance. My fellow graduate studentsMahlini Sood, Kim D. Reynolds, Alec Dawson, Marcia Meldrum, and Judith Traverswere thoughtful critics and valued friends whose companionship helped sustain me in numerous ways. My initial archival research brought me into contact with Ruth Crocker, Joan Waugh, Scott Sandage, and Sarah Lederman, each of whom generously shared early versions of their work on philanthropy and scientific charity and commented on mine. Our conversations and collaboration on various conference panels and forums helped me clarify and hone key aspects of my argument.

As I began the arduous process of converting my dissertation into a book, I incurred a number of new debts. The incisive and detailed comments provided by David Hammack and Dwight Burlingame, the series editors at Indiana University Press, aided me enormously in this process and helped improve the final quality of this book in countless ways. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Brent Ruswick and to the anonymous reviewers who carefully read and commented on the entire manuscript for their valuable input and suggestions, and to Julia Turner for her excellent copyediting. Many thanks also to Sue Hoye, Nina Brown, Patricia Ortman, Malini Sood, and Kim D. Reynolds, who provided advice, editorial suggestions, and technical assistance of varying forms.

I received crucial institutional support at all stages of this project. My initial research was funded by grants and fellowships from the Center for the Study of Philanthropy at the City University of New York, the Indiana University Center on Philanthropy, and the Aspen Institute. The Community College of Baltimore County, my academic home for the past seventeen years, granted the sabbatical and reduced teaching load that enabled me to see this project to its completion. Gary Dunham, Kate Schramm, Stephen Mathew Williams, and Darja Malcolm-Clarke of Indiana University Press helped guide me through various aspects of the publication process and the librarians and archivists at the Butler Library at Columbia University, the New York Public Library, the Museum of the City of New York, and the New-York Historical Society provided critical assistance with documents, photographs, and images.

To the dear friends who have been part of this journey, and to all the extended family members of the Greeley and Frantz clans, who have grown too numerous to list, thank you for the affection, support, and laughter you have provided me over these many years and for the expressions of interest you have shown in this project. And finally, to my husband, Ed, and my daughter, Emily, the two great loves of my life, I offer my profound and heartfelt gratitude for your love, patience, and twisted humor. Your presence in my life has brought me more joy and inspiration than you can possibly know. It is with a full heart that I lovingly dedicate this book to you.

BEYOND

BENEVOLENCE

IN MARCH 1915, A WEALTHY New York socialite threw a lavish dinner party at her palatial Fifth Avenue home. The gathering, touted as one of the social events of the season, was widely reported in the society pages of the citys newspapers. A few days later the hostess, Mrs. Rockwell-Jones, received a letter from a seventeen-year-old girl named Mary Dart. The young stranger explained that both she and her father were currently out of work and that her family of nine was growing destitute. She then politely but matter-of-factly asked her would-be benefactor to send them some food.

Mrs. Rockwell-Jones had received many such begging letters over the years. In the past, she had dealt with these requests in person by putting on some old clothes and hunting out the addresses of these people, meeting them face to face and helping according to her own judgment. In recent years, however, she had come to rely on charitable agencies to investigate the merits and needs of the people who appealed to her for assistance and to distribute alms when deemed appropriate. Mary Darts letter thus made its way into the hands of the New York Charity Organization Society (COS). In addition to the investigative services it provided to individuals like Rockwell-Jones, the society maintained a confidential social service exchange where cooperating charities could share and obtain information about alms-seeking individuals like Mary Dart. In this way, two other letters that Miss Dart had written to wealthy women, referred to two different charitable agencies, ended up at the COS. A charity worker was dispatched to the Dart home and found the family to be in great need. They were assisted with rent and food, and Mary was helped to find a new job at a hotel.