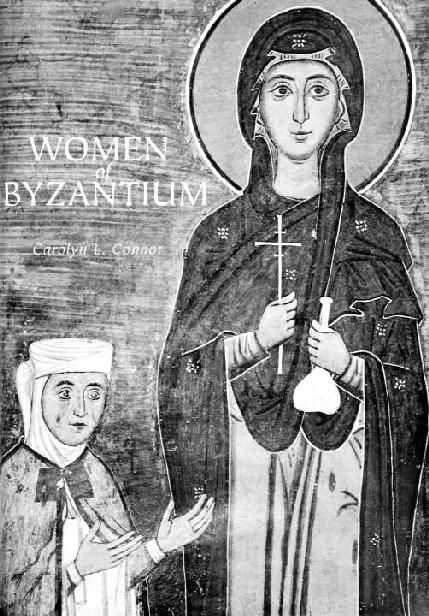

WOMEN OF BYZANTIUM

WOMEN

of

Carolyn C. Connor

To my students

CONTENTS

PART I. LATE ANTIQUITY (250-500 CE)

PART If. EARLY BYZANTIUM (500-843)

PART III. THE MIDDLE BYZANTINE PERIOD (843-1204)

PART IV. LATE BYZANTIUM (1204-1453)

Colorplates follow page 2o6

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge the financial assistance of the University Research Council at the University of North Carolina in helping subsidize the production of color plates. At Yale University Press I would like to thank Harry Haskell in particular for his patience, understanding, and helpful good humor in seeing this book through to completion. Without him it never would have completed the journey. I also cordially thank Larisa Heimert, Keith T. Condon, and Lawrence Kenney for their editorial assistance.

INTRODUCTION

Everyone has a story. Given a chance to tell it, most people will recount the events that shaped their lives in explaining how they arrived at where they are. At any given time one's life-story is necessarily a composite view of his or her life up to that time, seen from a perspective that defines successes and failures, choices and chance happenings, hopes and realities, all of which composes a more or less coherent picture. When a person's story is told by others as remembered after his or her life is completed, sometimes by a friend or sometimes someone far removed in time, with that person motivated by certain agendas, it inevitably becomes more selective, with the advantages of hindsight shaping the author's memory and intent. It is with an awareness of these various patterns and origins of our personal histories and the ways in which memory functions that I now approach the stories of Byzantine women, seemingly so far removed in time and culture-or are they?

Histories of the early Christian and medieval East, the lands now occupied by the modern states of Greece, Turkey, and the Near East, once the heartland of Byzantium, have dealt primarily with political events, administrative decisions, and military conquests. It is no wonder that women are barely mentioned in these accounts, for men held the offices, led the armies, and made most of the decisions that shaped the political map during the first millennium and a half of the common era. The absence of women in the historical records of a patriarchal, postclassical civilization would not be surprising. Is the history of Byzantine women therefore unrecoverable? Beyond their biological roles as bearers and nurturers of children, women played different roles from men, sometimes less visible in public life but nonetheless crucial in the operation and makeup of society. Their occupations, beliefs, and social roles significantly shaped the culture and sometimes intersected with spheres of male activity. They could and did rule the empire in their own right; their choices in marriage often determined male rulers, and their influence and leadership affected matters of state. Hence an alertness to issues of gender is essential in understanding Byzantine society as a whole as well as the place women held in that society. By gender I mean, above all, the social roles ascribed to men and women. Gender, and what happens when gender roles are bent, will play an important part in the work of writing women back into the histories of Byzantium!

As it turns out, women are very much present in the abundant surviving sources: saints' lives, chronicles, polemical treatises, biographies, legal records, among many others. In addition, art, artifacts, and buildings hold important testimonies about women. Byzantinists have demonstrated just how numerous and meaningful these records are. In this book I have tried to assimilate and build upon the broad experience and interdisciplinary range of my colleagues in Byzantine studies, to all of whom I am greatly indebted. Recent advances and new directions in scholarship in a number of fields and involving a range of approaches have shown there is actually much more information about Byzantine women than one would imagine. In the past several decades Byzantinists have delved into archives and legal and monastic records and made considerable progress in gathering and quantifying statistics and in revealing patterns of women's lives. Literary, historical, and religious documents are being read in new ways, thanks in part to the heightened awareness brought about by the application of some theoretical approaches. Archaeological and art historical evidence-from buildings and their decoration in sculpture, mosaics, and frescoes to jewelry, enameling, illuminated manuscripts, and small artifacts-is being analyzed with a new eye to women's objectives and connections to symbolic expression. Thanks to recent exhibitions and the publication of catalogues of Byzantine art the public at large can now visualize the material splendor and everyday objects of that civilization as never before. Society is in a different place too because of the maturing of the feminist movement. Commentators have moved beyond documenting their exclusion and oppression to showing the achievements and importance of women's contributions historically. Many scholars have responded with new kinds of studies of texts and images. This book is part of that response to a perceived need to frame and situate the women who were integral to Byzantine culture within their various contexts, in their many roles.

Scholars of Byzantine studies have been inclined to publish more for the academic or the specialist than for a broad readership. This is understandable since Byzantium and its ancient roots are not as well known as, say, the history of western Europe in the Middle Ages, and a certain amount of background and technical expertise is required, as in gaining the skills necessary to read ancient and foreign languages. It is also a field in which scholars habitually work across a number of disciplines and fields: history, philology, art history, archaeology, literary criticism, numismatics, religion, classical studies, medieval studies, women's studies, and others. Although some efforts have been made to alleviate the problem of speaking to a wider audience, studies of Byzantine women still present barriers in the foreignness of terms and in assumptions that readers are acquainted with the customs and the ways the society functioned. What is still needed is to draw together and present in a clear, contextualized, and accessible way the stories of the women of Byzantium, for if one looks first at key concepts and defines essential terms, this exciting material can be dealt with firsthand, opening a door to modern readers. Making accessible the rich material on Byzantine women is my first concern in this book.

Because women played such a vital part in Byzantine civilization, from its origins in the first centuries of the common era to the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, it is important to look at the whole spectrum of Byzantine history. In this way one sees women as situated firmly within Byzantine culture as a whole and as central rather than peripheral to the society-aims which are reflected in this book's structure. Organization is by part and chapter and follows a chronology of the civilization, from its classical roots in late antiquity, around 250 to 500 CE, to the late Byzantine period, between 1204 and the end of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. For convenience, the parts correspond to four successive periods. An introduction to each part outlines major events, issues of transition, dynastic lines, or short case studies by way of example. Within each of the four parts, individual chapters take up a series of topics, such as women and pilgrimage, imperial marriage, patronage, monasticism, etc. As I introduce background in that topic, along with terms, major issues, and the approach to be taken in that chapter, I pose questions which naturally arise in connection with the topic. In the second part of each chapter, a case study focuses on a historical woman, as I explore the primary text or texts most revealing about that person, in conjunction with telling images.