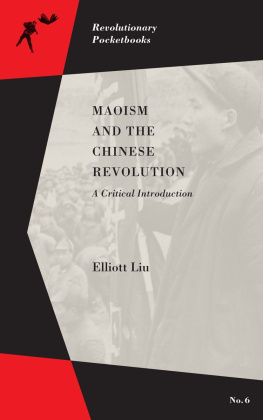

Revolutionary Pocketbooks

Eclipse and Re-emergence of the Communist Movement Gilles Dauv and Franois Martin

Voices of the Paris Commune edited by Mitchell Abidor

From Crisis to Communisation Gilles Dauv

Death to Bourgeois Society: The Propagandists of the Deed edited by Mitchell Abidor

Maoism and the Chinese Revolution: A Critical Introduction Elliott Liu

Anarchy and the Sex Question: Essays on Women and Emancipation, 18961917

Emma Goldman edited by Shawn P. Wilbur

For a Libertarian Communism

Daniel Gurin

Note: This book draws on many sources from different time periods and thus mixes Wade-Giles and Pinyin forms of transliteration. The author has done his best to standardize names and places.

Maoism and the Chinese Revolution: A Critical Introduction

Elliott Liu

This edition copyright 2016 PM Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-62963-1-370

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930959

Cover by John Yates/Stealworks

Layout by Jonathan Rowland based on work by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Copublished with:

thoughtcrime ink

C/O Black Cat Press

4508 118 Avenue

Edmonton, Alberta T5W 1A9

www.thoughtcrimeink.com

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com

To my mother and father,

and to my partners and comrades.

CONTENTS

CONTENTSWho are our enemies? Who are our friends? This is a question of the first importance for the revolution.

Mao Tse-tung, Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society, 1926

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTIONThe Chinese Revolution was one of the great world-historical revolutions of the twentieth century. It included the overthrow of a dynastic system that had governed China for over two thousand years; a period of rapid modernization and the growth of anarchist and communist politics in East Asia; two decades of mobile rural warfare, culminating in the triumph of a state socialist project; and finally, a series of external conflicts and internal upheavals that brought the country to the brink of civil war and led to the emergence of the capitalist dreadnought that stands to shape the course of the twenty-first century. One fruit of this rich historical experience is Maoism.

The term Maoism is used to describe syntheses of the theory and strategy that Mao Zedong developed from the 1920s to the 1970s, alongside his allies in the Chinese Communist Party. Different political tendencies use the word to foreground different elements of Maos thought and practice, but in its various iterations Maoism has made a great impact on the U.S. revolutionary left. In the 1960s, many groups in the black liberation, Chicano, and Puerto Rican movements, and later the New Communist movement, looked to China for inspiration. Maos influence continues today not only in well-established groups such as the Revolutionary Communist Party and the two Freedom Road Socialist Organizations, but also through younger groupings such as the Revolutionary Student Coordinating Committee and the New Afrikan Black Panther PartyPrison Chapter. If a wave of social movement is to appear in the United States in the coming years, Maoist politics are likely to be a significant element of its revolutionary wing.

Given the persistence of Maoism, todays revolutionaries must ask: What are the central pillars of Maoist politics, in their various forms? In what historical circumstances did these elements emerge, and how were they shaped by their context? How have these ideas been interpreted and applied in revolutionary movements? How might these politics help or hinder us in developing a revolutionary movement for today? This book offers a set of preliminary answers to these questions. In the pages below, I provide a brief survey of the fifty-year Chinese revolutionary experience for militants who are unfamiliar with it, and contextualize the main elements of Maoist politics within that history. Along the way, I offer a critical analysis of the Chinese Revolution and Maoist politics from an anarchist and communist perspective.

While I disagree with him on particulars, my take on the revolution is in broad agreement with the central claims of Loren Goldners controversial Notes Toward a Critique of Maoism, published online in October 2012. The Chinese Revolution was a remarkable popular peasant war led by Marxist-Leninists. Taking the helm of an underdeveloped country in the absence of a global revolution, the Chinese Communist Party acted as a surrogate bourgeoisie, developing the economy in a manner that could be called state capitalist. The exploitation and accumulation around which Chinese society was subsequently organized transformed the party into a new ruling class, with interests distinct from those of the Chinese proletariat and peasantry. Maos wing of the party tried to evade the problems of bureaucratization and authoritarianism, using the Soviet experience as blueprint and foil. But even as they called forth popular movements, Mao and his allies were continually forced to choose between sanctioning the overthrow of the system that guaranteed their class position or repressing the very popular energies they claimed to represent. Mao and his allies repeatedly chose the latter, beating back the revolutionary self-activity of the Chinese proletariat and ultimately clearing the way for openly capitalist rule after Maos death.

My take on the various components of Maoist politics varies, depending on the philosophical, theoretical, strategic, or methodological element in question. In general, I consider Maoism to be an internal critique of Stalinism that fails to break with Stalinism. Over many years, Mao developed a critical understanding of Soviet society, and of the negative symptoms it displayed. But at the same time, he failed to locate the cause of these symptoms in the capitalist social relations of the USSR and so retained many shared assumptions with the Stalinist model in his own thinking. Thus Maos politics remained fundamentally Stalinist in character, critiquing the USSR from a position as untenable in theory as it was eventually proven in practice. This book makes an initial attempt to interrogate Maoist concepts in this context. Other militants will have to carry the task further. Only when Maoism is subjected to an immanent critique and digested in this manner will it be possible to effectively re-embed elements of Maoism in a coherent political project adequate to our present situation.

To develop our account further, we must examine the broad arc of the Chinese revolutionary experience. We begin at the transition from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, when modern China was born in toil and bloodshed.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS