T he author would like to thank a number of people for their help during the research and writing of this book.

First to the staff of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry, both in London and Derry, whose assistance throughout was exemplary and invaluable.

Second to my first employers, at Open Democracy, who allowed me to start attending hearings and forgave me when the subjects of this book took me over.

Third to my family, friends, and particularly Marco, for putting up with me through the months and years that this subject and book stole all my attention.

Also to Ruth and Crispian, who read it first, gave invaluable advice, and corrected mistakes. Any errors that remain are my own. Also to Rafe and Kevin for reviewing drafts and assisting with a mountain of research materials during writing.

Finally to my agent, Gillon Aitken, and Iain Dale, Sam Carter and everyone at Biteback Publishing.

T his book is about a set of individuals whose stories echo further than Britain or Northern Ireland. Among them are people who cannot believe that anything bad can be done by their own side as well as people who believe no good can be done by their enemies. There are people who are ready to forgive and people who refuse to forget. There are people from all sides who are sorry for their actions and those from all sides who will never admit guilt or express an apology.

This book is about something else as well: what happens when ordinary people are thrown into the middle of horrific events. And what forgiveness can ever mean when all the killers are loose.

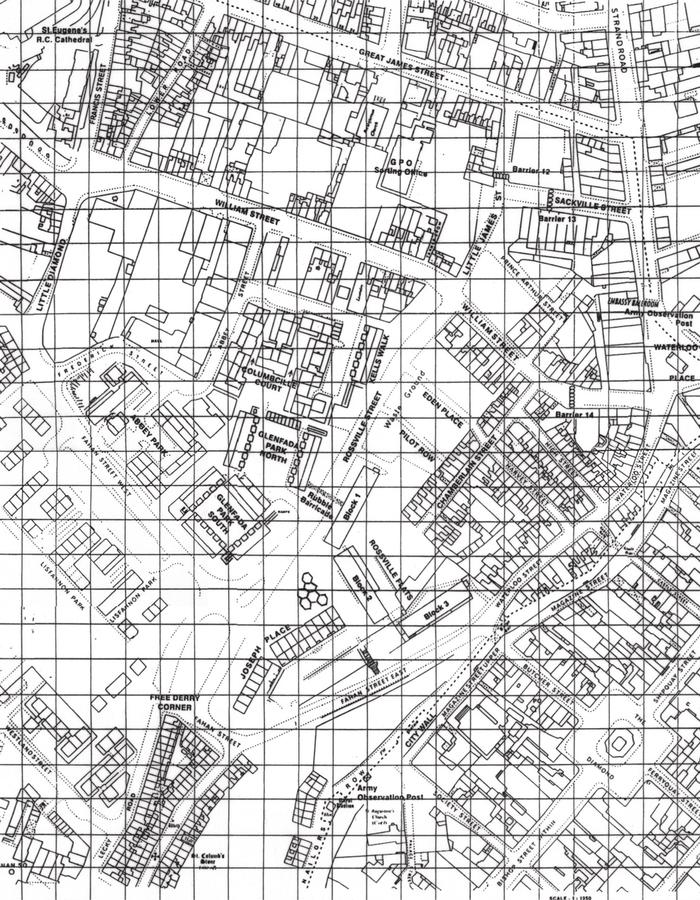

On the afternoon of 30 January 1972 a civil rights march set off from the Creggan area of the city of Derry in Northern Ireland. The crowd of around 10,000 aimed to finish up with speeches at the Guildhall Square in the heart of the city. They never got there.

Fearful of clashes, the security forces prevented the march from heading into the centre and rerouted it into the Bogside area. Some marchers began to riot against the army at barricades that had been erected. Stones were thrown, teargas and rubber bullets fired in response. Then everything changed. Shots were fired. The 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment went over the barricades, ostensibly to scoop up rioters, but actually headed deep into the Bogside. In the space of a few minutes twenty-one of the soldiers fired a total of 108 rounds in an area filled with fleeing marchers and civilians.

By the time firing stopped thirteen civilians lay dead on the streets. Fifteen more were wounded. One died a few months later.

It was the worst massacre of British citizens by British troops since Peterloo in 1819 and a landmark low point of the Northern Irish conflict one of a few seminal moments that escalated a bloody and internecine conflict into a long-drawn-out and sadistic civil war. That conflict, which became known as The Troubles, staggered on for another three decades, claiming three and a half thousand lives. Its embers are not yet out.

What happened that day was a source of terrible dispute from the moment it occurred. Army commanders claimed that, on entering the Bogside, British troops had come under heavy fire from civilian nail-bombers and gunmen and had shot at them. Community leaders and civilians denied any such thing: innocent civilians had been gunned down in cold blood, they said. In an effort to settle the matter, the British government set up an Inquiry into the events under the chairmanship of the then Lord Chief Justice, Lord Widgery. It broadly found in favour of the armys version of events.

This verdict ground dirt into the already existing wound of Bloody Sunday. The idea that the British state, including the judicial system, had colluded with the British army in murdering Catholics became entrenched, vindicating and making alluring for some the claims of the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Many years after these events a new British Prime Minister stood up to address the House of Commons. Full of hope, and with colossal public goodwill behind him, in 1998 Tony Blair announced that the British government was going to set up another Inquiry into what happened that day. It was to be chaired by another British peer, Mark Saville. By the time Lord Saville started work many of those involved were dead. Many others were to be summoned out of retirement to attempt to recall, and account for, events in their youth. At last the truth would be discovered. And there would be a very different result.

What ensued was a monumental task. The Inquiry was not only the lengthiest and most detailed but also the costliest in legal history and became a huge matter of controversy itself. Saville and the two Commonwealth judges who sat with him were expected to report within a couple of years at a cost of a few million pounds. In fact the report took another twelve years. By the time Saville did report back it was not to the Prime Minister who had set him off on the task. Both that Prime Minister and his successor had left office and it fell to a new Conservative Prime Minister to announce the Inquirys findings.

Meanwhile, as the costs rose towards 200 million the Saville Inquiry became the object of ridicule and disdain from the media, depicted as a gravy-train for lawyers. As a result of the vast cost and the even vaster quantities of time and documentation involved, much of the wealth of new information that Saville turned up was lost: lost to recriminations over cost, lost to recriminations over time, and lost on a media that, with few exceptions, gave up on the proceedings as they dragged interminably on.

In 2002 the Inquiry transferred from Derry to London to hear from military, political and intelligence witnesses before returning to Derry to hear from the IRA. Interest had waned, but I started attending daily. Firstly because I wanted to hear the evidence first-hand to hear from the soldiers and the IRA who were there that day and who had fired. If anybody was going to have the key to the mysteries of what happened that day it would be these men. I wanted to hear if the Republican stories were true. Or if the British army had been maligned. Perhaps nobody was telling the truth? I knew this would be the last chance to find out.

But there was another reason I attended. The hatred and distrust that led to that day and were embedded by that day remain strong. Many British people think that they have heard quite enough about Bloody Sunday. They believe that Irish Republicans and their sympathisers have had quite enough attention directed at this event. As a result Bloody Sunday has been a tragedy that few non-Republicans have looked into. That should be addressed. Bloody Sunday was not only a Derry tragedy, it was a British tragedy and one with serious repercussions for the way in which the army, the judiciary and the state should operate.

Because the day had become Republican holy ground it had also been manipulated. As the Inquiry progressed it became clear that the British army were not the only army to open fire in the Bogside that day. The IRA and their sympathisers did not want these facts to come out, indeed did everything they could to stop them, but, as this book shows, the real story of Bloody Sunday turns out to be not only more straightforward than the British army would like to admit, but more complex than the IRA have ever said.