CONTENTS

From where I live, in a modest quarter of Sydneys eastern suburbs, I often frequent the cafe hub of Double Bay. It is there that I find my favourite comfort, slipping back to my cultural roots, the languid bohemia of central Europe wherein my memory at leastthe daily dose of swing is to sit around in espresso bars, high on caffeine, endlessly discussing mainly two subjects: politics and football. This does not just go on in Budapest by the way. Its the same in Athens, Rome, Prague, Madrid, Lisbon, Vienna, Rio, Buenos Aires, Tel Aviv and Damascus. In Britain and other parts of northern Europe, you can substitute pub for coffee house. Thats the only difference. The planet is dotted with clusters of humanity, like lesions brought on by an incurable plague, endlessly preoccupied by the principal things that concern them, one of which is football. I have observed this all my life and continue to do so. As a child in Budapest I would pass outdoor cafes where grown men, smoking cigarettes and gulping down short blacks, would chatter endlessly on about football. They would still be there four or five hours later. When I first walked across the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, the only locals among the hundreds of tourists on the bridge were two gentlemen, with copies of La Gazzetta Dello Sport tucked under their arms, debating why and how Fiorentina had lost to Juventus the previous day. Two hours on, they were still at it. In Verona, at a cafe on the Piazza Br, two elderly gents, dapperly dressed, argued feverishly at the table next to mine. Shakespeare came to mind, except that these gentlemen of Verona had only one subject that concerned them: football. In Rome during the 1990 World Cup, while lunching at our constitutional trattoria, Johnny Warren and I noticed an unholy row going on between an elegant young man and a striking woman at another table. The waiter told us their marriage was safe. They were arguing over whether or not Roberto Baggio should start in Italys next game. Much has been said about the astronomical numbers of people who watch the World Cup, or the hundreds of millions who play football, but I wouldnt mind getting a figure on how many people around the world sit around in cafes and bars talking football on any given day, and how long they spend doing it.

I make this point for a number of reasons, one of which is to propose that the universal affection in which football is held is not restricted to the couple of hours during which matches are played but is a continuous, endless thing, consuming interest and curiosity for many waking hours of, I would guess, billions around the planet, every day for most of their lives. Sure, there are parts of the globe, such as North America, where other sports dominate conversations. But the numbers would be small by global comparisons. This is not only because football happens to be the worlds most popular sport, it is also because football, uniquely, seems to be a cause for intellectual stimulus, argument and debate. Hence its second home, away from the fields and the stadiums, in the coffee houses that, historically, have been venues for intellectual discourse and ferment since the seventeenth century. Isaac Newton would frequent The Grecian coffee house in Londons Devereux Street to parley with other scientists. In the modern era, science has made way for less exhausting and challenging preoccupations, football principal among them.

But why is this so? Why is football so dominant in everyday thought around the globe? Why does one football match, like the final of the 2006 World Cup, command 3 billion television viewers, almost half the worlds population? Why is it the worlds most popular sport? Why was it that, in the first place, football conquered almost the entire planet when any one of a number of other sports might have done so instead?

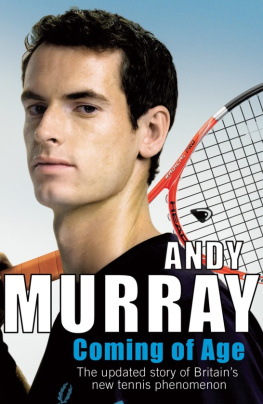

An Australian fan appears to pray for divine intervention during a public broadcast in Sydney of the Australia v Italy 2006 World Cup clash in Germany, a match won 10 by Italy in the 90th minute.

To deal with the last question first, it was partly an accident of history. More about this in the next chapter, but the principal cause of footballs being able to plant seeds around the world ahead of other sports is that at the time, towards the end of the nineteenth century, football had already conquered Britain, and Britain was then the greatest source of influence in global development. As the Industrial Revolution galloped forward everywhere, with Britain as its chieftain, it was natural that Britains favourite sport, like everything else British that acted as a model for the rest of the world, would be taken up by its conquered subjects.

But why football and why not rugby, or cricket, or tennis, or hockey? Why not another of the myriad other sports that also began to prosper in Britain at the time?

We should note, as a precursor to answering these questions, that footballs root source of joy is in playing it, not watching it. The universal love football commands is usually measured by the numbers of its television viewers and how often the turnstiles click at its stadiums around the world. But probably more important is the numbers that play it, for the vast majority of its fans once played it or at least have tried to play it. It is through that experience that players of whatever standard, and those close to them, graduate to fandom. David Goldblatt, recalling the games pioneering days in his excellent work, The Ball Is Round: A Global History of Football (Penguin), puts this into historical context:

The fin-de-sicle gentleman player could have played whatever he wantedfootball was not the only option left after financial and social costs had been discounted. People played because they just loved to play. Once seen, the prospect of trying it out for yourself was irresistible. We can reasonably argue that many of the reasons that make football a particularly good game to watch applied to playing it too: its continuous flow, its unpredictability, its combination of teamwork and individual bravado, its respect for both mental and physical labour.

The principal edge that football had then on other sports, and continues to have, is its accessibility, that it can be played by anyone: rich, poor, tall, short, skinny, fat, old, young, black, white, man, woman. Football does not distinguish or prejudge, apart from deeming that wins and losses are determined only by ability. This is the ultimate strength of football. It is the core source of its capacity to conquer and woo, for it places the spectator in the position of a would-be, wish-I-was player, even a would-be star player, the onlooker harbouring the supposition that he is no different from the man on the field, save for the latters superior and enviable ability. This cannot be said of most other sports in which social accessibility, affordability of equipment, physical attributes and gender disallow opportunity and therefore make improbable such a personal relationship between watcher and player.

Given that football is so easy and cheap to playsimple rules, minimal equipment, no restrictions on space or timeits appeal to the poor, and therefore the masses, delivers and guarantees its broad popularity. When the British first began to plant the seeds of football in foreign lands, they did so with a game that was primarily still for the gentry. In the main the British engineers, schoolteachers, businessmen and diplomats who began forming teams in South America and elsewhere in the late nineteenth century had no conscious intent to popularise the game in those lands. All they wanted was to play it themselves. But the games bewitching appeal soon gripped the local populations and it was especially appealing to the poor working classes.